Liberty Bond Drivers Had Long-Lived Effects on Investor Behavior

Can early financial experiences affect lifelong investment decisions? A new study finds that one of America’s largest financial literacy campaigns—the Liberty Bond drives of World War I—influenced household investment behavior long after the war bonds had been repaid.

In ‘Invest!’: Liberty Bonds and Stock Ownership over the Twentieth Century (NBER Working Paper 33541), Gillian Brunet, Eric Hilt, and Matthew S. Jaremski study the nationwide Liberty Bond drives of 1917–19. These campaigns aimed to finance America’s participation in World War I while increasing financial literacy. The government enlisted celebrities, investment banks, and millions of volunteers to sell bonds through door-to-door solicitations, parades, and public events. Schoolchildren were taught the basics of compound interest and saving while adults were exposed to messages associating investing with patriotism and financial security. For many Americans, Liberty Bonds were their first experience with a financial asset beyond a bank account.

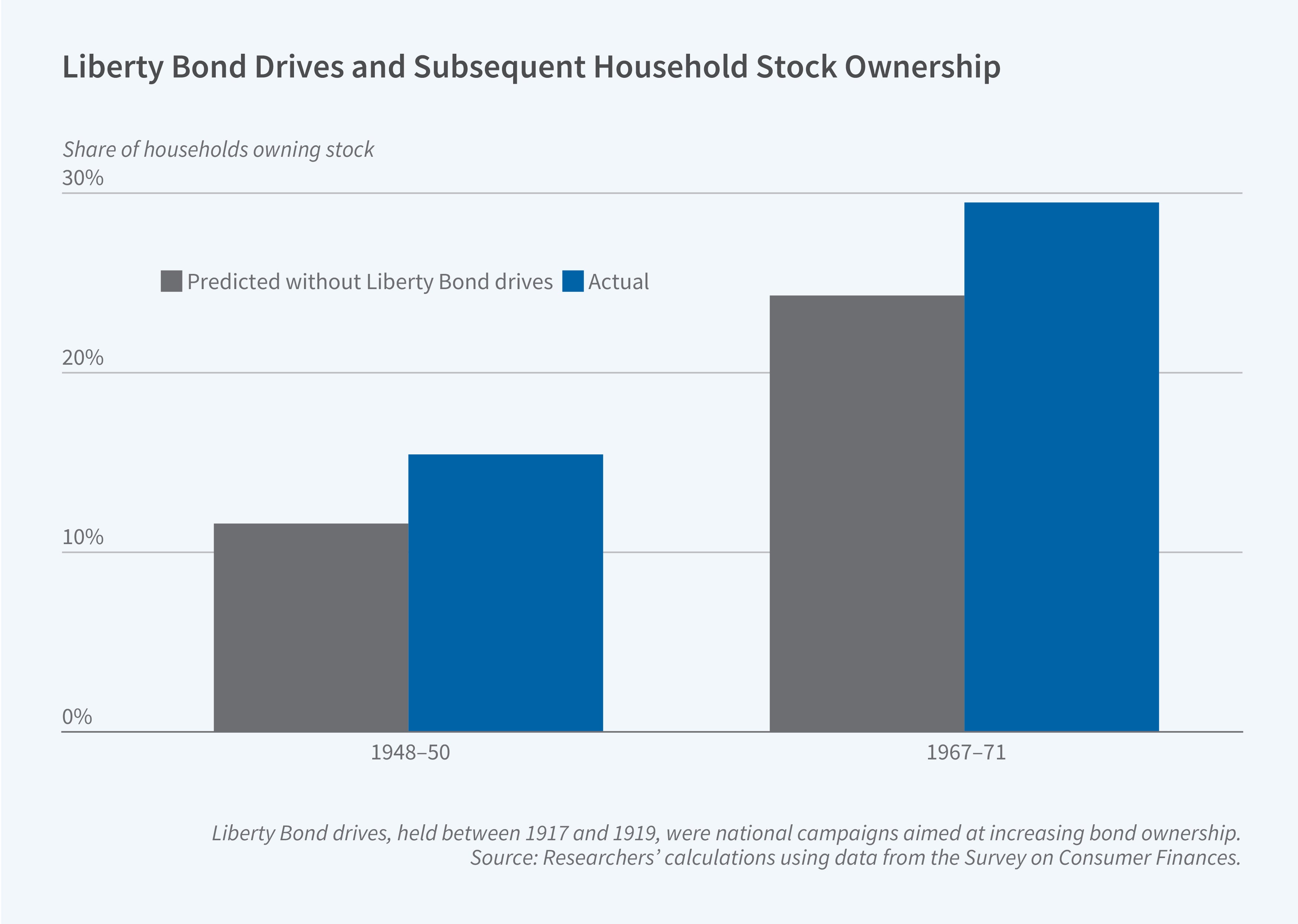

Areas with greater exposure to WWI Liberty Bond drives exhibited higher rates of stock ownership for decades afterward.

To measure the long-term effects of these campaigns, the researchers use household-level data from the Survey of Consumer Finances from 1947 through 1971 matched with county-level data on Liberty Bond participation rates. These participation rates reflect varying levels of exposure to Liberty Bond drives across different counties. There were substantial idiosyncratic elements to the roll-out of bond campaigns across counties, and these campaigns were not simply targeted at high-income or high-wealth areas.

In counties with higher Liberty Bond participation rates during WWI, the researchers find significantly higher rates of stock and bond ownership in 1947 and subsequent decades. This relationship emerges even after controlling for income, education, demographics, and homeownership. A 1 standard deviation increase in Liberty Bond participation raised the probability of owning stocks by 0.9 percentage points, bonds by 1.7 percentage points, and a bank account by 2 percentage points. To place these results in context, roughly 17 percent of households owned stocks, 40 percent bonds, and 78 percent bank accounts during the 1947–71 period studied. The asset ownership effects were present only among individuals who were at least school-age during WWI, and not among cohorts in the same counties who were too young to be exposed to the bond campaigns, suggesting that the findings are not attributable to persistent county characteristics.

Beyond portfolio choices, the Liberty Bond campaigns also shaped attitudes toward investing. Households in counties with higher Liberty Bond participation were more likely to believe that it was wise to use extra money to invest in stocks rather than bonds, and they were also more likely to report saving for retirement or major purchases than for emergencies or other reasons.