Italian Catholic Churches’ Role in the Assimilation of Immigrants

Rising international migration flows have sparked heated debate on the effects of immigrants on host societies. A recurring concern is that cultural differences between immigrants and the native born and the insularity of some immigrant communities threaten social cohesion and national identity. Such concerns are often linked to religion, which is not only a dimension along which immigrants and natives tend to differ, but also an important determinant of culture, beliefs, and morals.

In Faith and Assimilation: Italian Immigrants in the US (NBER Working Paper 30003), Stefano Gagliarducci and Marco Tabellini explore how ethnic religious organizations influence immigrants’ social, cultural, and economic assimilation in host societies. They focus on Italian Catholic churches in the United States between 1890 and 1920, the Age of Mass Migration. During this period, 4 million Italians moved to America and anti-Catholic sentiments were widespread. The researchers collect and digitize detailed historical records on the arrival and presence of Italian Catholic priests and churches that were specifically identified as serving the Italian community. By combining this information with US census data, they can trace the effects of religious organizations on immigrants’ integration.

Immigrants in communities served by these churches displayed higher labor force participation but had lower quality jobs and a lower rate of naturalization.

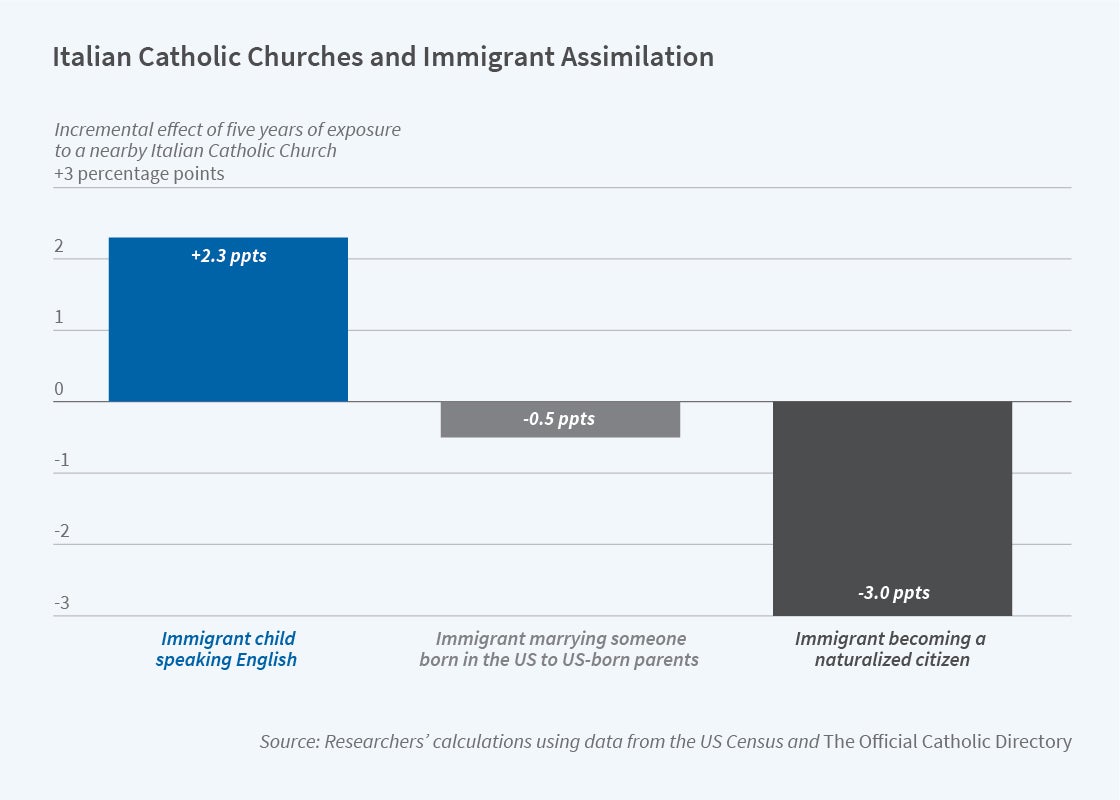

Access to Italian Catholic churches lowered the probability that Italian immigrants married or integrated with native-born people of native parentage. Five additional years of exposure to an Italian Catholic church reduced intermarriage rates and residential integration by 0.5 and 2 percentage points, respectively — 61 percent and 13 percent relative to the 1900 mean.

Exposure to Italian churches also lowered immigrants’ naturalization rates, suggesting less interest in political participation, and increased parental desire to transmit their culture and values to the next generation. Exploiting naming patterns within Italian families, the researchers show that children born to immigrants after an Italian church was established near them were more likely to be named after a Catholic saint relative to siblings born in the US of the same parents before the arrival of the church.

Italian churches had ambiguous effects on immigrants’ economic outcomes. With their presence, Italians’ labor force participation increased but their occupational standing and the quality of their jobs decreased. Moreover, Italian immigrants living in counties more exposed to these churches were more likely to specialize in what were thought of as “Italian” occupations, such as bootblack, barber, and fruit grader. The patterns suggest that Italian priests made it easier for immigrants to find jobs via their ethnic networks, but that such jobs limited the opportunities for occupational upgrading.

While the findings suggest that Italian churches reduced the social and economic assimilation of Italian immigrants, they may have helped immigrants on other dimensions, including by providing education. Catholic churches often were associated with schools for immigrant children. The researchers find that immigrant children born in Italy who grew up in US counties with longer exposure to Italian churches were more likely to speak English and to be literate. They find that this pattern was more pronounced in areas with an Italian church with an associated school.

— Lauri Scherer