Intended and Unintended Health Effects of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs

Almost all US states have implemented an electronic prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) over the past 25 years in an effort to mitigate the risks of prescription drug abuse. Providers, pharmacists, and law enforcement can query these web-based databases, which track prescriptions of controlled substances within each state. PDMPs facilitate identification of potential misuse by patients and excessive prescribing by providers. Kentucky introduced the first electronic PDMP in July 1999 and two decades later Missouri was the only state without one.

In Behavioral Responses to Supply-Side Drug Policy during the Opioid Epidemic (NBER Working Paper 29596), Simone Balestra, Helge Liebert, Nicole Maestas and Tisamarie B. Sherry document the effects of PDMPs on opioid prescriptions, heroin use, drug-related hospitalizations, and fatal overdoses. To identify the impact of these programs, the researchers bring together numerous datasets and take advantage of the staggered introduction of PDMPs across states over time.

Using a large database of private insurance claims, the researchers demonstrate that the volume of prescriptions written for opioids falls after PDMPs are implemented. Specifically, the number of patients who receive an opioid prescription declines by 13 percent. However, the dosage and duration of prescriptions do not change.

Reduced prescriptions affect both chronic users of prescription opioids (those who have had prescriptions for at least 90 days) and new users of opioids. Prescriptions to new users fall by 23 percent, while prescriptions to chronic users fall by 12 percent. The researchers caution that abrupt discontinuation of prescriptions to chronic users could be problematic if these patients have developed a dependence and experience withdrawal symptoms.

Some patients respond to reduced access to prescription opioids by seeking prescriptions from out-of-state providers, purchasing diverted prescriptions from secondary markets, or obtaining heroin from illicit markets. Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicate that PDMPs are associated with an 8 percent increase in the share of people who report using heroin, but no change in the likelihood of seeking or receiving substance abuse treatment. The researchers estimate that one out of every six prescription opioid users who lose access to prescription opioids after PDMP introduction respond by initiating heroin consumption.

Overall, opioid-related hospitalizations, as reported in the National Inpatient Sample, are unaffected by PDMPs. However, important compositional changes underlie this finding. Hospitalizations due to prescription opioid use decrease by 7 percent on average after a PDMP is introduced, while hospitalizations due to heroin use increase by 8 percent. Emergency hospitalizations for heroin overdoses increase by 11 percent.

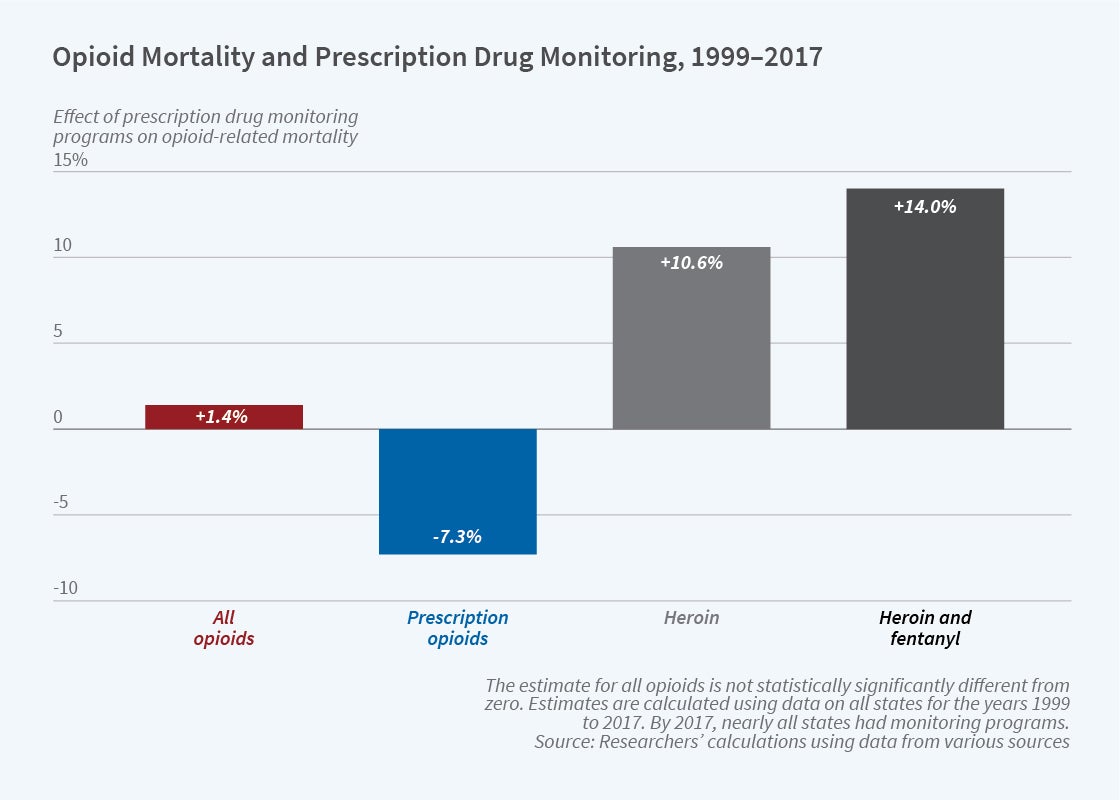

Similar patterns are apparent in fatal opioid overdoses, calculated from Vital Statistics mortality data and summarized in the figure. Although mortality from semi-synthetic opioids — a category that includes common prescription medications such as oxycodone and hydrocodone — declines by 7 percent after the implementation of a PDMP, aggregate mortality from opioid overdoses does not change. Instead, the reduction in deaths attributable to prescription opioids is fully offset by fatal overdoses due to heroin and fentanyl (which is often mixed with, or sold as, heroin).

The study highlights that PDMPs have both intended and unintended health effects. Consistent with the objectives of policymakers, PDMPs decrease the use of prescription opioids and reduce consequent health risks including hospitalizations and fatal overdoses. However, behavioral responses of opioid users counteract the intended effects of PDMPs. Increased use of illicit opioids and the elevated hospitalizations and fatalities attributable to those drugs substantially offset the health benefits of PDMPs. These results suggest that supply-side restrictions alone are not sufficient to address the misuse of prescription opioids and that such policies in tandem with demand-side interventions, such as improved access to evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder and related social service supports, may warrant consideration.

Maestas and Sherry acknowledge funding from the National Institute on Aging (P01AG005842) and a gift from Owen and Linda Robinson.