Financial Reporting Practices and Firm Productivity

Why do seemingly identical firms produce such different outcomes? In US manufacturing, plants at the 90th percentile produce twice the output of those at the 10th percentile using the same inputs. This enormous productivity dispersion persists even after controlling for management quality, information technology (IT) adoption, and capital intensity. A missing piece of the puzzle: firms differ substantially in how they measure and report their economic activity. These differences matter. Financial reporting quality, defined as the rigor with which firms track, verify, and disclose their operations, explains as much productivity variation as management practices or information technology adoption. This operates through two channels: better information for managers and more accurate measurement for economists.

In Measurement Matters: Financial Reporting and Productivity (NBER Working Paper 34536), John M. Barrios, Brian C. Fujiy, Petro Lisowsky, and Michael Minnis exploit a unique institutional feature of the US: private firms face no mandatory audit requirement, creating variation in reporting practices. They assemble three novel datasets covering different segments of the private sector: new audit questions added to the 2021 US Census Bureau’s Management and Organizational Practices Survey, comprehensive tax return data from the Internal Revenue Service for medium and large firms between 2008 and 2010, and detailed financial records for smaller enterprises between 2002 and 2008 from Sageworks. This allows them to directly measure how financial reporting choices affect both actual and measured productivity.

Variation in the quality of financial accounting reporting can explain more than 10 percent of the dispersion in productivity across private US firms.

Their central finding: variation in financial reporting quality explains 10–20 percent of within-industry productivity dispersion, a magnitude comparable to that attributed to IT or structured management practices. They also find that firms with audited financial statements are 10–12 percent more productive than similar firms without external verification. These effects are robust to matching on size, industry, and capital structure, ruling out simple selection stories in which better-run firms merely choose better accounting. The relationship appears across all three datasets, spanning manufacturing, services, construction, and wholesale trade.

How could audits raise productivity? First, audits function as information technology. Better accounting provides managers with clearer signals about the operation of their business, enabling a more efficient resource allocation. Consistent with this mechanism, the productivity gains are concentrated where information matters most: in competitive, low-margin industries where small efficiency improvements determine survival, and among young firms still learning how to operate. The effect is muted in R&D-intensive industries, where current accounting practices have little to say about tomorrow’s innovation.

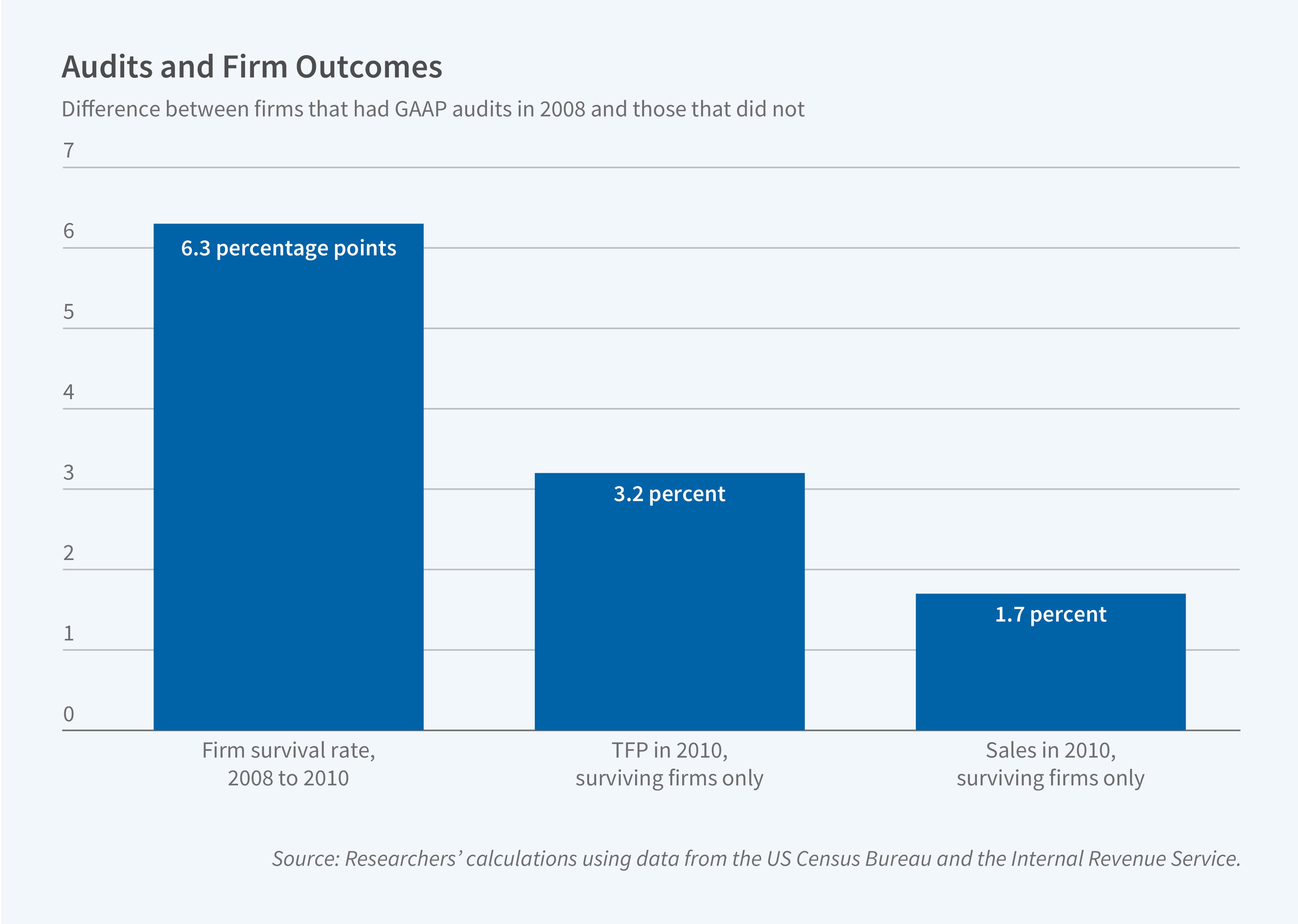

The timing of the effects supports the information story. Productivity jumps in the second year after firms adopt audits, but not the first, which is exactly what one would expect if managers need time to learn from better data. Firms with higher reporting quality are also 7 percent more likely to survive a two-year window, holding initial productivity constant. Thus, better measurement predicts survival independently of current performance.

The second channel is measurement bias. Without auditors, firms have the incentive and ability to underreport output to minimize taxes. Using cross-state variation in corporate tax rates as a natural experiment, the authors show that the productivity premium from auditing is twice as large in high-tax states (California) as in low-tax states (Texas). Audits don’t just improve management; they also clean the data statistical agencies use to measure productivity in the first place. This matters for interpreting productivity statistics as some of the measured dispersion reflects differences in reporting, not economics.