How the Gig Economy Supports Entrepreneurial Activity

Jobs in which self-employed individuals can regulate their working hours reduce the risk of launching new businesses by providing an income fallback.

In the gig economy, software platforms provide self-employed individuals with easy access to flexible work opportunities. Gig workers contract with platform owners to provide on-demand services to their clients on a per-task basis. As independent contractors, these workers can determine how much they will work by accepting or refusing jobs. Unlike traditional freelance workers, those in the gig economy do not need to invest in marketing to a customer base, maintaining accounting systems, or establishing a company; those tasks are handled by the software platform.

In Launching with a Parachute: The Gig Economy and New Business Formation (NBER Working Paper 27183), John M. Barrios, Yael V. Hochberg, and Hanyi Yi show that the expansion of the gig economy increases entrepreneurial activity by making it less costly for entrepreneurs to supplement their incomes while developing their own businesses. The gig economy provides an income fallback if an entrepreneurial business fails.

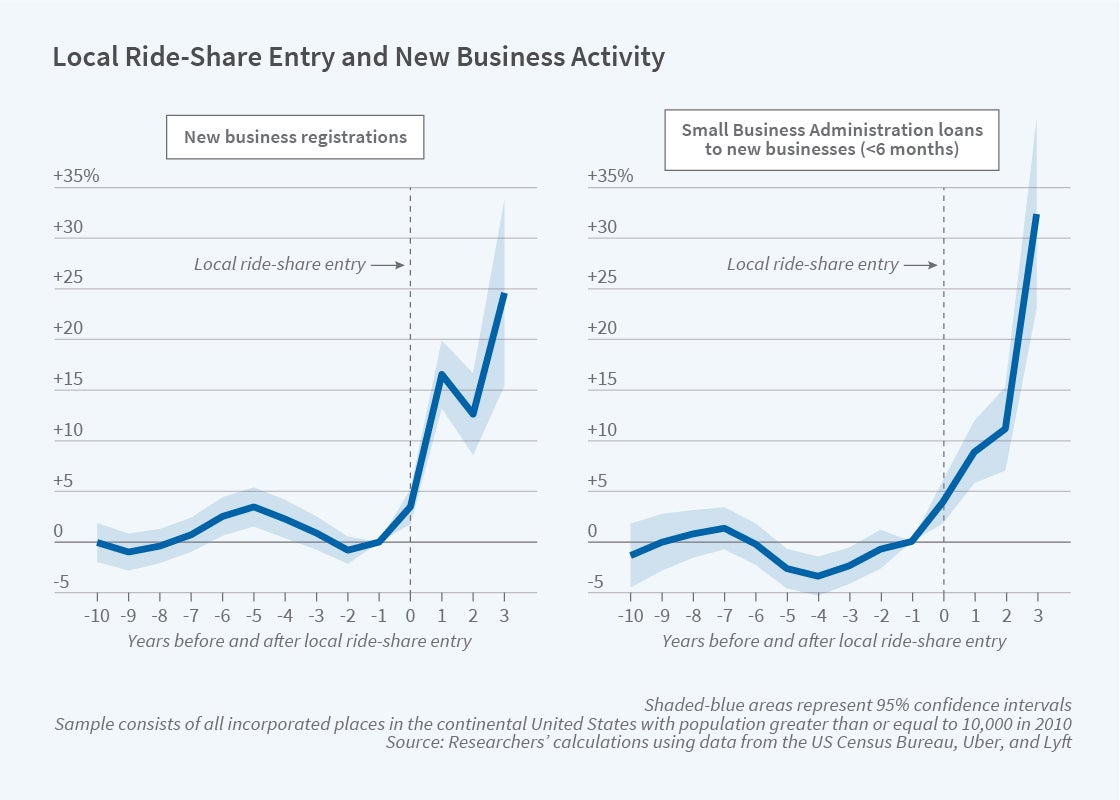

Tracking ride-hailing service rollouts in cities across the United States from 2010 through 2016, the researchers show that new business registrations in a city increased by 4 to 6 percent after Uber or Lyft became active there. Small business lending to newly registered businesses increased by a similar magnitude, and Google searches related to entrepreneurship increased by 7 to 13 percent.

The data underlying these results include all incorporated places in the continental United States with a population greater than or equal to 10,000 in 2010. The average city had a population of 54,000. After a slow start in 2010, ride-hailing companies entered new cities at a rapid pace after 2013. By 2016, 1,193 of the 2,959 cities in the sample had an active ride-hailing service that could serve as an income source for entrepreneurs.

Counts of new for-profit businesses registered with the secretaries of state by ZIP Code and quarter allowed the researchers to observe the full universe of entrepreneurial entry at the micro level. As the vast majority of new business launches are financed either with the entrepreneur’s savings or some form of debt, businesses registered in the prior 6 to 12 months were matched with data on Small Business Administration loans.

Entrepreneurial entry was larger in cities with lower income levels, lower education levels, poorer credit scores, higher fractions of Hispanic population, and lower fractions of Black and African American population. Across cities in the sample, median per capita income was $37,100, the median percentage of high school graduates was 87.4, the median percentage of the Hispanic population was 9.1, and the median percentage of the Black and African American population was 7.7. Cities with higher volatility in wage growth before the arrival of ride hailing enjoyed increases in new business registrations that were between 1 and 2 percent higher than in cities with more stable wage growth. The researchers used a 1 percent sample of credit bureau records from 2010 to calculate the average personal income and credit score for each city. After ride hailing arrived, entrepreneurial activity was greatest in cities in the worst and the best quartiles of the credit score distribution.

The researchers conclude that the availability of gig economy jobs has a positive spillover effect on entrepreneurial activity. The benefit is larger in cities with worse socioeconomic conditions.

—Linda Gorman