The Two Life Cycles of Human Creativity

At what stage of their lives are great innovators most creative?

There are two very different answers to this question. Some great innovators make their most important discoveries suddenly, very early in their careers. In contrast, others arrive at their major contributions gradually, late in their lives, after decades of work. Which of these two life cycles a particular innovator follows is related systematically to his conception of his discipline, how he works, and to the nature of his contribution.

My research on this issue began when I first set out to develop quantitative measures of the quality of the work of important individual modern painters over the course of their lives.2 Since then, these measurements have led not only to a new and more systematic understanding of the sources of innovation in modern art, but also to a more general and comprehensive framework for analyzing the creativity of individuals in a wide range of intellectual activities. After explaining the application of this analysis to the careers of modern painters, this report will demonstrate how its implications have illuminated the history of modern art, and then will show briefly how the analysis can be extended to innovators in other disciplines.

Seekers and Finders

Like important scholars, important artists are innovators.3 Great modern artists can be divided into two groups, defined according to differences in their goals, methods, and contributions.

Painters who have produced experimental innovations have been motivated by aesthetic criteria: they have aimed at presenting visual perceptions. Their goals are imprecise, so their procedure is tentative and incremental. The imprecision of their goals means that they rarely feel they have succeeded, so their careers are often dominated by the pursuit of a single objective. These artists paint the same subject many times, gradually changing its treatment by trial and error. They consider the production of a painting as a process of searching, in which they aim to discover the image in the course of making it. They build their skills slowly over the course of their careers, and their innovations emerge piecemeal in a body of work.

In contrast, painters who have made conceptual innovations have intended to communicate specific ideas or emotions. Their goals for a particular work can be stated precisely in advance. They often make detailed preparatory plans for their paintings, and execute their final works systematically. Conceptual innovations appear suddenly, as a new idea produces a result quite different not only from other artists' work, but also from the artist's own previous work. Conceptual innovations are consequently often embodied in individual breakthrough paintings. The conceptual artist's certainty about his goals, and confidence that he has achieved them, often leaves him free to pursue new and different goals. Unlike the continuity of the work of the experimental artist, conceptual artists' careers are therefore often characterized by discontinuity.

The long periods of trial and error usually required for important experimental innovations mean that they tend to occur late in an artist's career. Conceptual innovations are made more quickly, and can occur at any age. Yet radical conceptual innovations depend on the ability to perceive and appreciate extreme deviations from existing practices, and this ability tends to decline with experience, as habits of thought become more firmly established. The most important conceptual innovations therefore generally occur early in an artist's career.

Archetypes

Two of the greatest modern artists epitomize the two types of innovator.

Paul Cézanne was an experimental innovator. A month before his death in 1906, the 67-year-old Cézanne wrote to a friend:

Now it seems to me that I see better and that I think more correctly about the direction of my studies. Will I ever attain the end for which I have striven so much and so long? I hope so, but as long as it is not attained a vague state of uneasiness persists which will not disappear until I have reached port, that is until I have realized something which develops better than in the past... So I continue to study... I am always studying after nature, and it seems to me that I make slow progress.4

This brief passage expresses nearly all the characteristics of the experimental artist -- the visual criteria, the view of his enterprise as research, the incremental nature and slow pace of his progress, the absorption in the pursuit of a vague and elusive goal, and the frustration with his perceived lack of success in achieving that goal of "realization." The critic Roger Fry explained that Cézanne's frustration was a consequence of his uncertain attitude and incremental approach:

For him as I understand his work, the ultimate synthesis of a design was never revealed in a flash; rather he approached it with infinite precautions ... For him the synthesis was an asymptote toward which he was forever approaching without ever quite reaching it.5

The irony of Cézanne's fear of failure at the end of his life stems from the fact that it was his most recent work, the paintings of his last few years, that would soon come to be considered his greatest contribution, and would directly influence every important artistic development of the decades that followed.

Unlike Cézanne, who told a friend "I seek in painting," the leading artist of the next generation, Pablo Picasso, confidently declared "I don't seek; I find."6 In 1923 Picasso stated that:

The several manners I have used in my art must not be considered as an evolution or as steps toward an unknown ideal... I have never made trials or experiments. Whenever I have had something to say, I have said it in the manner in which I have felt it ought to be said.7

Generations of art historians have commented on the abruptness and frequency of Picasso's stylistic changes. One biographer made this point by comparing Picasso with Cézanne: "There was not one Picasso, but ten, twenty, always different, unpredictably changing, and in this he was the opposite of a Cézanne, whose work ... followed that logical, reasonable course to fruition."8 For Picasso, new ideas brought new styles, for his conceptual art was intended not to represent the appearance of his subjects, but rather his knowledge of them: "I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them."9

Picasso often planned his paintings carefully in advance. In 1907, at age 26, he painted Les Demoiselles d'Avignon after making more than 400 studies, "a quantity of preparatory work ... without parallel, for a single painting, in the entire history of art."10 The large canvas became his most famous work, for it served to announce the beginning of the conceptual Cubist movement, "the most complete and radical artistic revolution since the Renaissance."11

Quantifying Artistic Success

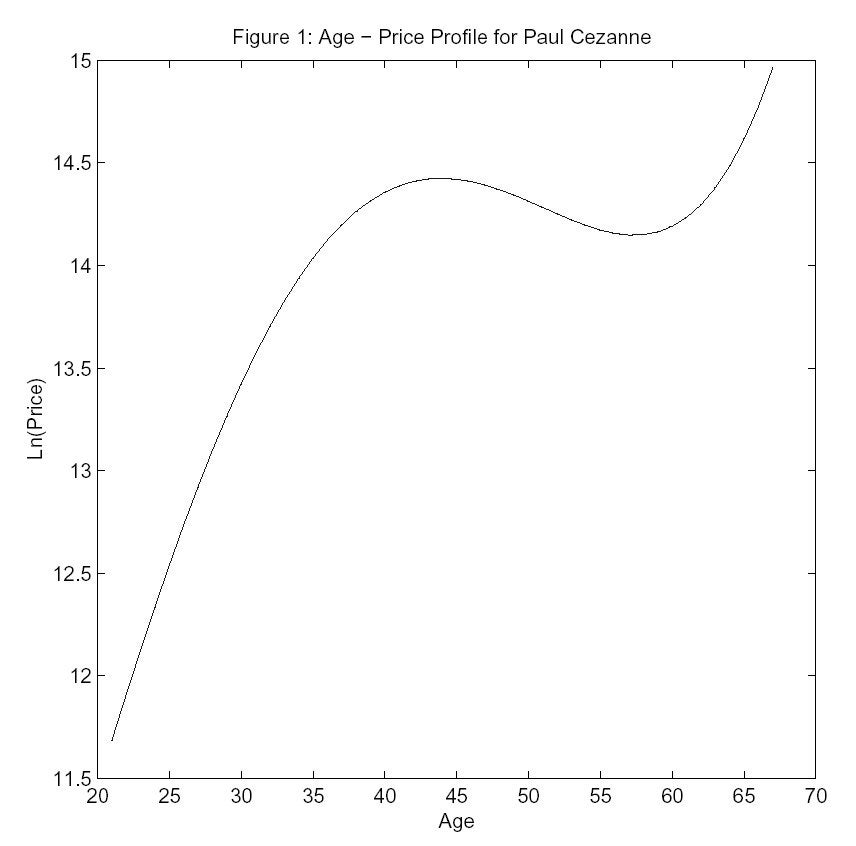

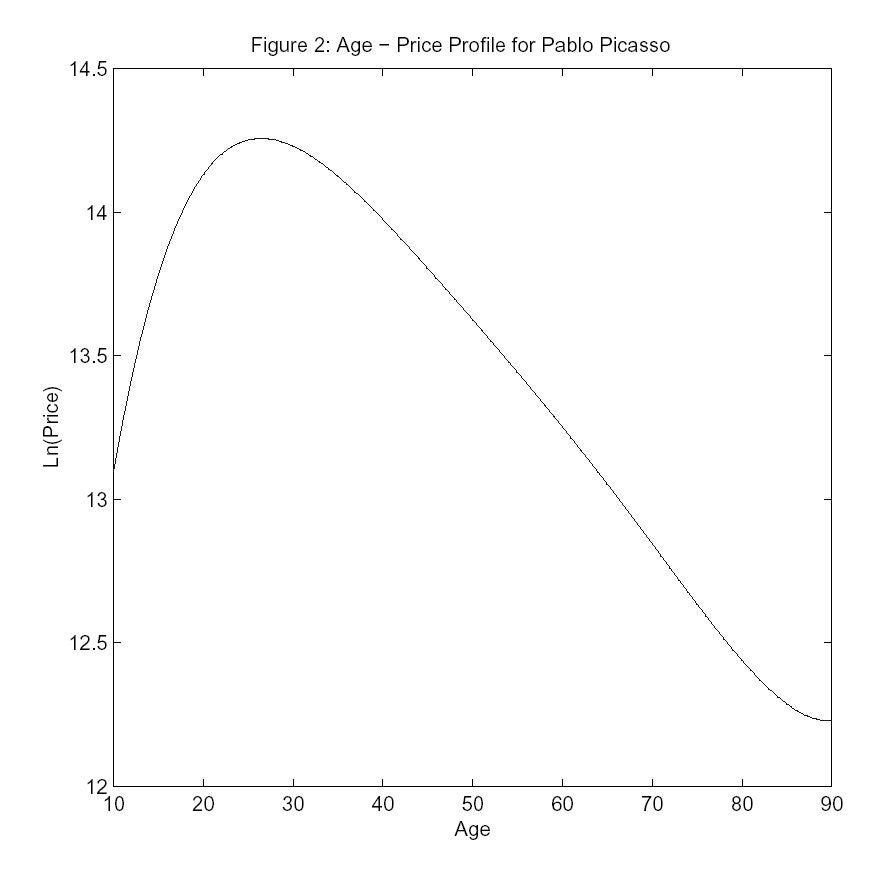

Regression analysis of all auction sales of paintings by Cézanne and Picasso during 1970-97 yields the age-price profiles of Figures 1 and 2.12 Cézanne's work rises in value to the end of his life, when he arrived at his most radical solutions to the problem of portraying nature without sacrificing depth and solidity. Picasso's most valuable work dates from 1907, the year he painted the Demoiselles d'Avignon.

Figures 1 and 2 obviously reflect the preferences of collectors. To compare these to the judgments of art scholars, I surveyed the paintings used as illustrations in textbooks. An analysis of 33 books published in English revealed that for both artists the single year represented by the largest number of illustrations is the same as that estimated to represent the artist's peak in value -- age 67 for Cézanne, and 26 for Picasso.13 Separate analysis of 31 books published in French yielded precisely the same results.14

I now have used these measures to study the careers of more than 125 important modern painters. The auction market and the textbooks almost always agree closely on when the painter produced his best work.15 Analysis of these painters' working methods, and of the nature of their innovations, furthermore, reveals that their life cycles almost always follow the predicted pattern: painters who worked experimentally have nearly always produced their best work late in their careers, whereas those whose innovations were conceptual have nearly always made their greatest contributions early. Thus such major experimental painters as Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Wasily Kandinsky, Georgia O'Keeffe, Jean Dubuffet, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning all reached their peak achievements after the age of 40. In contrast, such important conceptual innovators as Georges Seurat, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Georges Braque, Juan Gris, Giorgio de Chirico, Jasper Johns, and Frank Stella all made their greatest contributions before the age of 30.16

Masters and Masterpieces

Recognition of the differences in methods and products between experimental and conceptual painters helps to resolve a number of puzzles in the history of modern art. One of these involves a discrepancy between the greatest painters and the greatest paintings. Specifically, if we rank both painters and paintings according to total illustrations in textbooks, we find that some of the most important artists failed to produce important individual works, while some of the most important paintings were produced by painters who do not rank among the very most important artists.17

The analysis provided here points to the explanation. Great experimental painters, like Cézanne, Degas, and Monet, innovated gradually, making many small changes in their technique over the course of extended periods and many canvases, and their greatest contributions were not embodied in individual breakthrough works. Consequently, there is no consensus on which of their paintings best illustrates their achievements. In contrast, conceptual innovations normally are declared in specific breakthrough works. Thus at the age of 27 Seurat specifically designed Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte to illustrate his scientific approach to the use of color, and it became the most famous painting executed in the nineteenth century. Two decades later the 25-year-old Marcel Duchamp painted Nude Descending a Staircase to demonstrate his conception of the static representation of movement, and it became the third most famous painting produced in the twentieth century, behind only the Demoiselles d'Avignon and another landmark work, Guernica, by the conceptual Picasso. So the puzzle is resolved: important conceptual painters produce famous individual masterpieces, but great experimental painters do not, instead producing important bodies of work.

Beyond Modern Art

The implications of this research go beyond modern art. It is now clear that this analysis can be applied equally to great painters of the pre-modern era: Masaccio, Raphael, and Holbein were conceptual artists, whereas Leonardo, Titian, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt were experimental.18 But the applicability of the analysis goes beyond art in general, for I believe that in virtually all intellectual activities there are important practitioners of both types described here, and that in all these activities there are consequently two distinct life cycles of creativity.

Results from studies of innovators in three other disciplines provide support for this belief. One of these studies analyzes the life cycles of Nobel laureates in economics. Whereas such theorists as Kenneth Arrow, Gary Becker, Paul Samuelson, and Robert Solow all published their most often cited work before the age of 35, the empiricists Simon Kuznets and Theodore Schultz both published their most-cited work after the age of 50. Economic theorists work deductively, and innovate conceptually, while in contrast the empiricists Kuznets and Schultz worked inductively, and innovated experimentally.19

A second related study examines the careers of important modern American poets. The production of great poetry often is considered to be the exclusive domain of the young.20 But quantitative analysis of individual careers contradicts this belief. By the measure of poems reprinted in anthologies, the careers of E. E. Cummings, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Richard Wilbur were dominated by the work of their 20s and 30s, but in contrast Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Frost, Robert Lowell, Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, and William Carlos Williams all produced their major work in their 40s and beyond. The elegant and sophisticated poetry of Cummings, Eliot, Pound, and Wilbur grew primarily out of imagination and study of literary history, and was formulated conceptually, while Bishop, Frost, Lowell, Moore, Stevens, and Williams produced poetry rooted in real speech and experience, drawing on the observed reality of their daily lives to innovate experimentally.21

A third related study shows that the careers of great modern novelists have followed these same two patterns. Herman Melville, D.H. Lawrence, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway wrote with confidence and clarity of purpose to express their ideas and emotions, and produced conceptual masterpieces early in their careers. In contrast, Charles Dickens, Mark Twin, Henry James, Virginia Woolf, and William Faulkner worked tentatively toward better representations of the world they knew, and arrived at their greatest contributions only after decades of experimentation.22

The full implications of this research appear to be considerable, and remain to be pursued through study of innovators in other disciplines. The implications involve not only substance but also method, for the results I have obtained suggest that, contrary to the tendency of economists to study the life cycle only for groups of workers, it may be of considerable value to study the careers of important individual innovators. This work may eventually give us a more systematic understanding of human creativity wherever it occurs -- in artists' studios, scholars' studies, or computer scientists' cyberspace.

Endnotes

D. W. Galenson, "The Careers of Modern Artists: Evidence from Auctions of Contemporary Paintings," NBER Working Paper 6331, December 1997, and in Journal of Cultural Economics, 24 (2000), pp. 87-112.

For discussion see D. W. Galenson, Painting outside the Lines: Patterns of Creativity in Modern Art, Chapter 4, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

R. Shiff, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984, p. 222; F. Gilot and C. Lake, Life with Picasso, New York: Doubleday, 1964, p. 199.

W. Rubin, H. Seckel, and J. Cousins, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1994, pp. 14, 119.

D. W. Galenson, "The Lives of the Painters of Modern Life: The Careers of Artists in France from Impressionism to Cubism," NBER Working Paper 6888, January 1999.

D. W. Galenson, "Quantifying Artistic Success: Ranking French Painters -- and Paintings -- from Impressionism to Cubism," NBER Working Paper 7407, October 1999, and in Historical Methods, 35 (2002), pp. 5-20.

D. W. Galenson, "Measuring Masters and Masterpieces: French Rankings of French Painters and Paintings from Realism to Surrealism," NBER Working Paper 8266, May 2001, and in Histoire & Mesure, 17 (2002), pp. 47-85.

D. W. Galenson, Painting outside the Lines, Appendixes A and B; D. W. Galenson and B. A. Weinberg, "Age and the Quality of Work: The Case of Modern American Painters," NBER Working Paper 7122, May 1999, and in Journal of Political Economy, 108 (2000), pp. 761-77.

D. W. Galenson, "The Life Cycles of Modern Artists: Theory, Measurement, and Implications," NBER Working Paper 9539, March 2003; D. W. Galenson, "Was Jackson Pollock the Greatest Modern American Painter? A Quantitative Investigation," NBER Working Paper 8830, March 2002, and in Historical Methods, 35 (2002), pp. 117-28; D. W. Galenson, "The Life Cycles of Modern Artists," NBER Working Paper 8779, February 2002, and in World Economics, 3 (2002), pp. 161-78; D. W. Galenson, "The New York School vs. the School of Paris: Who Really Made the Most Important Art After World War II?," NBER Working Paper 9149, September 2002, and in Historical Methods, 35 (2002), pp. 141-53.

D. W. Galenson, "Masterpieces and Markets: Why the Most Famous Modern Paintings are not by American Artists," NBER Working Paper 8549, October 2001, and in Historical Methods, 35 (2002), pp. 63-75; D. W. Galenson, "The Disappearing Masterpiece," World Economics, 3 (2002), pp. 9-24.

D. W. Galenson and R. Jensen, "Young Geniuses and Old Masters: The Life Cycles of Great Artists from Masaccio to Jasper Johns," NBER Working Paper 8368, July 2001; R. Jensen, "Anticipating Artistic Behavior: New Research Tools for Art Historians," unpublished paper, University of Kentucky.

D. W. Galenson and B. A. Weinberg, "Creative Careers: Age and Creativity among Nobel Laureate Economists," in preparation.