Are EU Markets More Competitive than Those in the US?

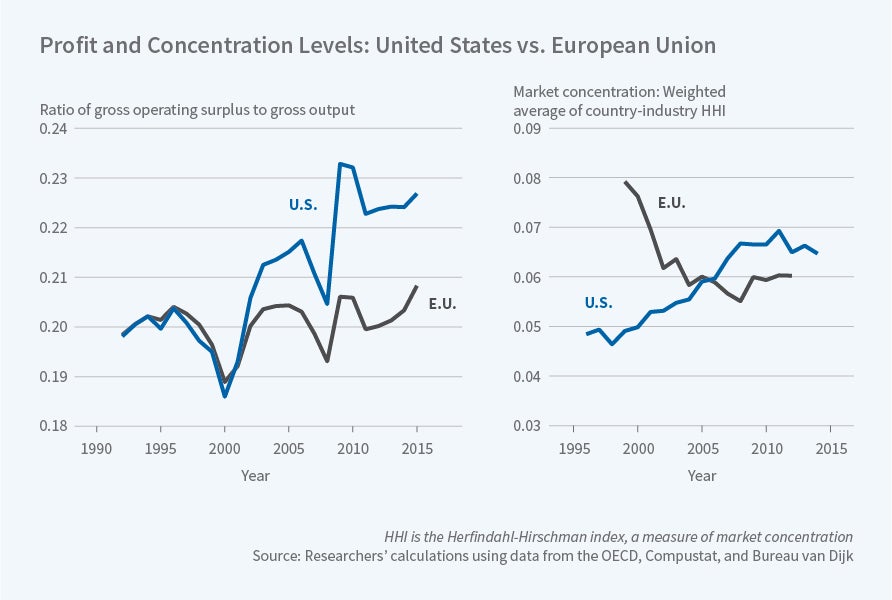

Since 2000, gross profit rates in the United States have risen and industry concentration has soared, but these trends are not found in the European Union.

Until the late 1990s, most U.S. markets were viewed as highly competitive relative to their international counterparts. Many European countries implemented U.S.-style free market regulatory models during this time period.

In How EU Markets Became More Competitive Than U.S. Markets: A Study of Institutional Drift (NBER Working Paper No. 24700), Germ�n Guti�rrez and Thomas Philippon argue that over the last two decades, U.S. markets have gradually become less competitive, and that, because this trend was not echoed in Europe, European markets today are actually more competitive than those in the United States. In many cases, the EU markets exhibit lower levels of industry concentration and excess profitability, as well as fewer regulatory barriers to entry.

The researchers find that starting around 2000, gross profit rates in the United States began to increase while the labor share declined. These developments are much more muted in the EU. A similar trend is observed in measures of industry concentration.

The researchers explore whether industry composition drove the divergence in concentration. They consider whether the emergence of high-tech industries drove the broad increase in concentration observed in the United States. They discount that explanation, noting that "the rise in U.S. concentration since 2000 is pervasive across most sectors, just as the stability/decline in EU concentration is." Industries that experienced significant increases in concentration in the United States, such as telecom and airlines, did not experience parallel changes in the EU.

In the airline industry, the researchers find, the "rise in U.S. concentration and profits closely aligns with a controversial merger wave that includes Delta-Northwest (2008), United-Continental (2010), Southwest-AirTran (2011) and American-US Airways (2014)."

They suggest that the divergence in market competitiveness between the U.S. and Europe is related to the powers granted to EU regulatory institutions at their inception. They note that both the European Central Bank and the Directorate-General for Competition were given more political independence than parallel institutions in the United States and thus have been able to pursue more aggressive antitrust enforcement in recent years. In the U.S. between 1996 and 2008, they write, the Federal Trade Commission "...essentially stopped enforcing mergers when the number of remaining competitors is 5 or more."

In all areas of antitrust the researchers find decreasing enforcement in the United States and increasing enforcement in the EU. The Directorate-General for Competition is more likely to pursue "abuse of dominance" cases than is the U.S. authority, and financial penalties in cartel cases tripled as a share of EU GDP between 2000 and 2016.

The decline in U.S. market competitiveness has had meaningful consequences for U.S. consumers, the researchers point out. Broadband internet prices in the U.S., for example, are significantly higher than in the EU, where the telecom industry is less concentrated.

They buttress their case for the comparative lack of political independence of U.S. regulatory bodies by noting the higher levels of both lobbying and campaign contributions in the U.S. than in the EU. Political campaign contributions are 50 times higher in the U.S. than in the EU.

— Dwyer Gunn