The Liquidity Cost of Private Equity Investments

Secondary market buyers of private equity limited partner stakes on average outperform sellers, but the market provides liquidity, enabling sellers to make otherwise impossible portfolio changes.

Substantial transactions costs are associated with investing in private equity funds, which are generally illiquid. Investors who wish to sell their positions in these funds tend to bear those transaction costs, according to The Liquidity Cost of Private Equity Investments: Evidence from Secondary Market Transactions (NBER Working Paper 22404). On average, buyers of these positions outperform sellers by a market-adjusted five percentage points per year.

Sellers tend to be traditional institutional investors, such as endowments and pension funds. When their liquidity needs or portfolio strategies change, they are eager to sell to buyers, who are mostly funds of funds, set up expressly to buy private equity investments.

"Transactions costs appear to be relatively high, most likely because of a limited number of participants and the asymmetric information about both funds and their portfolio firms," Taylor D. Nadauld, Berk A. Sensoy, Keith Vorkink, and Michael S. Weisbach report. "The liquidity cost of investing in this market [private equity] is substantial and one that investors should take account of when considering investing..."

Using privately obtained data from a leading intermediary in the secondary market for private equity stakes, the researchers measure the average cost of transactions between 2006 and 2014. The average discount to the net asset value (NAV) in these transactions was 13.8 percent, including the sale of very young funds during the financial crisis and very old funds after it. The discount for the most common type of sale—funds between four and nine years old—averaged nine percent.

Because NAVs aren't market-based valuations and, in some cases, can be manipulated by issuers, the researchers also study another measure, called the public market equivalent (PME), which equals the sum of the fund's discounted cash distributions to investors divided by the discounted cash investors put in. The discount rate is the cumulative return on the public equity market from the fund's inception to the cash flow being invested. A PME greater than 1 indicates a private equity fund outperformed this market. The PME is attractive because it eliminates the bias that could be associated with good vs. bad market timing in private equity transactions.

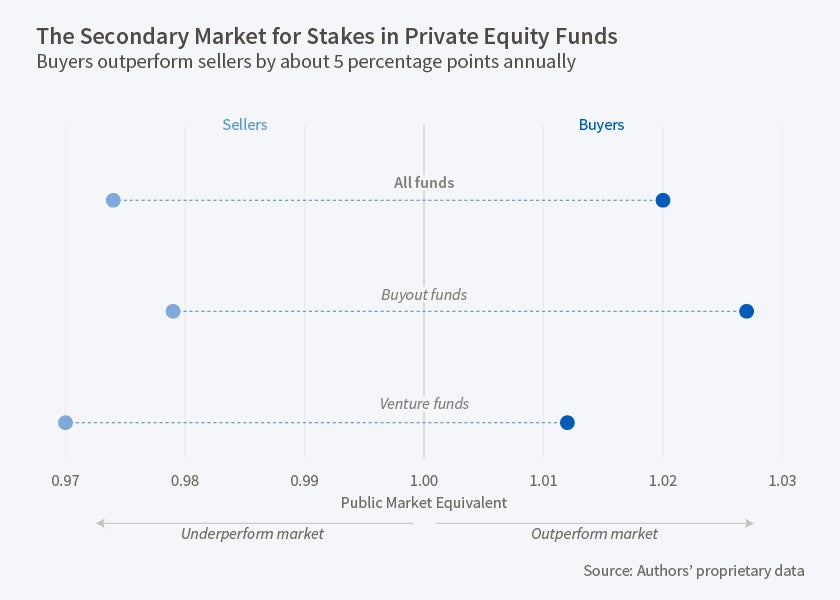

The analysis of PME data suggests that buyers still come out ahead, albeit with a smaller advantage. Using all transactions from 2006 to 2014, buyers averaged an annualized 1.02 PME (better, in other words, than if they had invested in the public stock market) compared with an annualized 0.97 PME for sellers—worse than public stocks. In the most common type of transaction, involving funds four to nine years old, buyers' average PME was 1.01 vs. sellers' 0.98. These numbers suggest that buyers outperformed sellers by about five percentage points in the first instance and three percentage points in the second.

The researchers observe that these differences are consistent with market microstructure theories, such as asymmetric information. For example, NAV discounts tend to be larger for smaller funds and smaller transactions, where the information costs per dollar invested are higher. NAV discounts and the differences between buyers' and sellers' returns are also larger when the economy is poor and there is less capital for purchases.

"The secondary market for limited partner stakes in private equity [funds] appears to be one in which buyers receive returns for supplying liquidity," the researchers conclude. "Sellers benefit because they are able to make strategic changes in their portfolios that, given the time horizon of private equity investments, would be impossible in the absence of a secondary market."

—Laurent Belsie