Matchmaker, Matchmaker, Watch Out for... Who?

Parental matchmaking in China often leads to relationships that economically and emotionally favor the parents relative to the young couples.

Those who have gone through the sometimes arduous mating ritual know that it's not always a case of romantic love at first sight. Some might even argue that the idea of a parental matchmaker intervening, as is common in some cultures to this day, might have its merits.

In Love, Money, and Parental Goods: Does Parental Matchmaking Matter? (NBER Working Paper 22586), Fali Huang, Ginger Zhe Jin, and Lixin Colin Xu provide new evidence on the consequences of such matchmaking. They find that parental involvement in matchmaking in China can lead to relationships that economically and emotionally favor the parents, not necessarily young couples. The income, independence, love, and marital bliss of those in parent-matched marriages can suffer as a result.

Cross-country patterns suggest that parents tend to meddle more in marriage arrangements if old-age care is not offered by society. In China, where the onus of old-age care usually falls upon a son and his wife, there is a long tradition of parents engaging in match-making marriages, particularly in rural areas.

The researchers studied the various financial and emotional trade-offs, both to parents and couples, of parental matchmaking by collecting and analyzing data from the Study of the Status of Contemporary Chinese Women, compiled by the Population Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Science and the Population Council of the United Nations in the early 1990s. The study included extensive interviews with thousands of married men and women from seven Chinese provinces.

The survey data reveal that 48 percent of rural couples and 14.5 percent of urban couples were married through parent-involved matchmaking, with the rest meeting and marrying either through their own searches or through friends. For rural couples, the lack of societal old-age and health care, as well as a lack of jobs and higher incomes, helped drive the tradition of parental matchmaking by both parents and their adult children. In contrast, urban couples, who lived in areas with more plentiful job opportunities, higher incomes, and societal welfare, relied less on parental matchmaking.

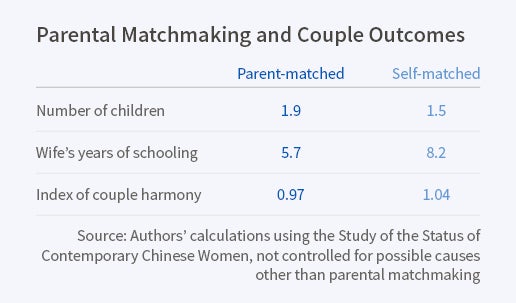

Boring down into the details of the extensive Study of the Status of Contemporary Chinese Women, the researchers extrapolate from the data that parent-involved marriages are associated with more submissive wives, a greater number of children, a higher likelihood of having a male child, and a stronger belief of the husband in providing old-age support to his parents. These marriages also display less marital harmony within the couples and lower market income of the wives.

Some parents put a higher altruistic premium on their adult children's love and harmony, while other parents are more focused on marriages that can provide them with adequate support in their old age and are particularly careful in how they network, screen, and nudge males and females into marriages. In the case of adult children, particularly males who are expected to provide care for their parents, they are often aware of the costs associated with parent-involved marriages and can either choose to "self-search" or rely on parental help in searching for spouses, particularly if the time, effort, expenses, and emotional strain of self-searching is deemed too great or too risky.

The researchers conclude that parental matchmaking involves a trade-off: "On the one hand, it entails agency costs in terms of less love within the couple. On the other hand, it helps to ensure parental goods for the matchmaking parents, and a more harmonious inter-generational relationship."

—Jay Fitzgerald