Workfare and Human Capital Investment: Evidence from India

A large workfare program in India led to increased school dropout rates and lower test scores among poor youth.

Dozens of nations in recent years have implemented programs guaranteeing employment on public works projects – workfare – in an effort to reduce poverty. In Workfare and Human Capital Investment: Evidence from India (NBER Working Paper 21543), Manisha Shah and Bryce Millett Steinberg examine the impact on human capital investment of one of the world's largest workfare programs, India's National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS).

The authors explore the possibility that workfare programs, which require beneficiaries to work on local public works projects in order to receive benefits, could increase the opportunity cost of schooling, lowering human capital investment even as incomes increase due to increased labor demand. They find that while NREGS may transfer resources to the poor, it also reduces educational attainment among adolescents.

India's National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, passed in 2005, created a program that provides rural households with up to 100 days of annual employment on public works projects at the local minimum wage. The program was introduced in 200 of the poorest districts in the country early in 2006. Another 130 districts were added to the program in 2007, followed by another 270 in 2008, when the program covered the entire country. By 2010, approximately 53 million households were participating in the program.

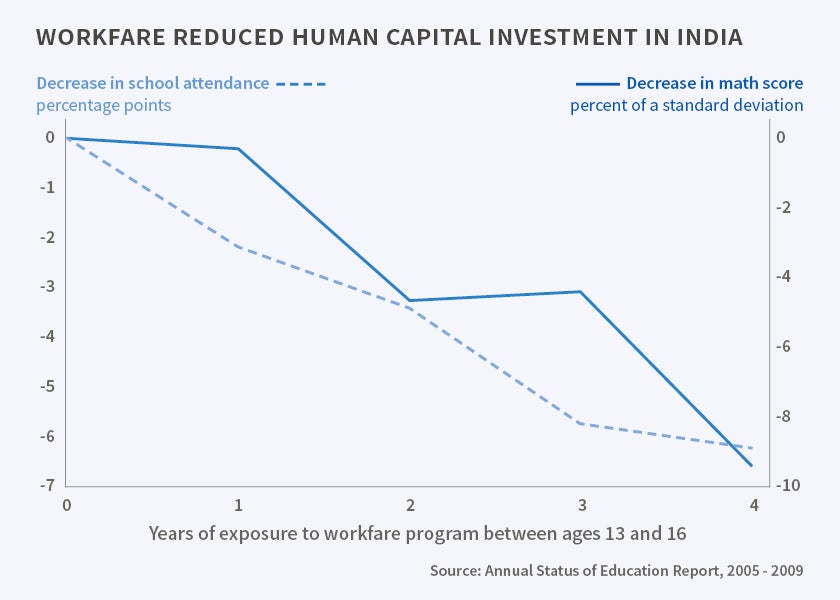

Analyzing changes in school enrollment rates and national test scores as the workfare program rolled out across India, the researchers find that enrollment and test scores both dropped following the program's introduction in a region. By 2010, five years after the program was introduced, between 650,000 and 2.5 million Indian adolescents may have quit school in favor of work, amounting to a significant loss in the development of human capital.

Each additional year of exposure to the program from 2006-09 saw math scores for 13- to 16-year-olds decrease by 2 percent of a standard deviation and enrollment rates fall by 2 percentage points.

The workfare program was designed in part to encourage the employment of females. However, the researchers report, the data sug-gest that while boys who left school took on jobs normally performed by men, girls who dropped out often were assuming domestic chores at home, most likely substituting for their mothers, whose labor force participation increased.

The impacts for younger children are mixed. In fact, exposure to NREGS during ages 2-4 may have increased test scores and en-rollment rates, likely because of increases in family income due to the program.

—Matt Nesvisky