University Innovation and the Professor's Privilege

When Norway changed its laws to give universities a major share of the profits from their professors' patents and startups, the rate of innovation was halved.

Prior to 2003, Norwegian researchers employed by universities retained blanket rights to the income from any new businesses they started and to the patents they received. Then, Norway adopted legislation that gave universities the rights to two-thirds of the returns from such activities.

In University Innovation and the Professor's Privilege (NBER Working Paper 22057), Hans K. Hvide and Benjamin F. Jones show that the rate at which Norwegian Ph.D.s employed by Norwegian universities started new businesses declined by more than 50 percent in response to this change.

Detailed workforce and employer data enable the identification of all university employees in Norway. The research combines these data with information on patent claims and business startups to investigate the consequences of the change in property rights.

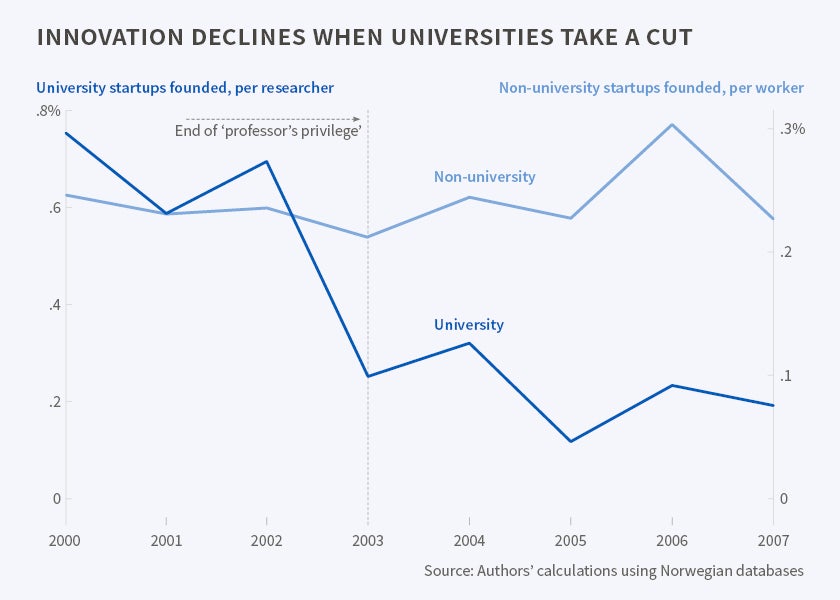

The researchers compare entrepreneurial activity when university workers retained all rights (2000-02) to entrepreneurial activity in the period after the law was changed (2003-07) and find that the percentage of university researchers who started a new firm in any given year dropped from 0.68 percent to 0.22 percent, a 67 percent decline. In contrast, the startup rate for the Norwegian population as a whole increased by six percent from the first period to the second. Relative to non-university-based Ph.D.s, the per capita start-up rate for university-based researchers declined 49 percent.

Following the change in the law, the number of patents obtained by university-affiliated researchers also fell sharply. Between 1995 and 2010, 431 university researchers produced 750 Norwegian patents, and trends in the annual number of patent grants to university researchers roughly tracked the non-university rate prior to 2003. After 2003, however, the patent rate per university researcher fell 48 percent compared to other Norwegian inventors. Patent quality also declined. Compared to patents from non-university inventors, patents produced by university-affiliated researchers after the change received about 25 percent fewer citations than those produced before it.

To gain another perspective on the decline in innovation, the researchers examined the patenting activities of firms owned by university-affiliated Ph.D.s. Prior to 2003, about 12 percent of firms founded by university-affiliated Ph.D.s obtained a Norwegian patent within five years of their founding. Only two percent received patents within five years after the law was changed.

Economic theory suggests deep challenges in effectively balancing property rights across investing parties. Intuitively, one may want to give a greater share of the property rights—and hence greater financial incentives—to the party whose investment matters more. From this perspective, the empirical findings following the property rights change in Norway suggest that university researchers, rather than the universities themselves, are especially important to innovative investments.

—Linda Gorman