When Glory Is Something to Die For

Inspired by the accomplishments of German air force aces to try harder, average pilots won few additional victories but perished at a much higher rate.

Whether it's students receiving academic recognition in school or professionals winning prestigious industry awards for their achievements, human beings crave and welcome praise—and this can sometimes spur extraordinary effort.

In Killer Incentives: Status Competition and Pilot Performance during World War II (NBER Working Paper 22992), Philipp Ager, Leonardo Bursztyn, and Hans-Joachim Voth examine the victory scores of thousands of German fighter pilots during the Second World War and find that official praise of a pilot led to significantly better performances by his former squadron peers. However, this extra achievement came at a lethal status-competition cost: Non-ace pilots strove to overachieve and sometimes paid the price with their lives.

Positive recognition of individuals can lead to increased effort and output within an institution or company—and such motivational tactics are widely used at all levels of society. Praise also can have negative effects, such as damaging morale among those who are not recognized. And it can spur status competition, a sort of striving to "keep up with the Joneses." The negative effects of praise can be particularly troublesome in high-risk situations, especially if the status competition involves genuine danger.

This study measures the effects of both positive recognition and status competition, focusing on the spillover effects of praise on the performance and risk-taking of former squadron peers in the German air force during World War II. Using war records compiled by the air force's high command (Oberkommando der Luftwaffe, or OKL) and now stored in the German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv) in Freiburg, the researchers review data on more than 5,000 fighter pilots, 53,008 claims of aerial victories, and a total of about 96,000 observation data points. They also identify and track official recognition of pilots by name in the daily bulletin of the German armed forces (Wehrmachtbericht), mentions that were considered one of the highest forms of recognition within the German military. They find that positive mentions in the daily bulletin of former peers who had been assigned to other Luftwaffe squadrons led to higher performance by these past squadron-mates and even among "birthplace peers" who grew up near a pilot who had received mention in the bulletin.

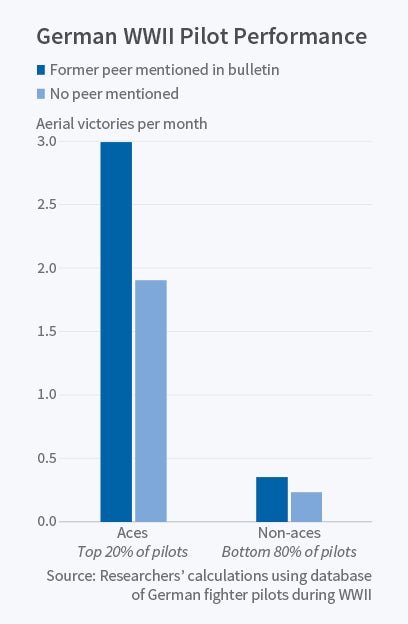

The extent of improved performance varied with the skill sets of the pilots. Aces, those ranked in the top percentile of German pilots, temporarily increased their victory scores by two-thirds. Those in the 90th percentile increased their scores by about one-fifth. At the lower end of the pilot skill distribution, pilots performed better after a former squadron peer was mentioned in the bulletin, but not by nearly as much as higher-ranked pilots.

The researchers study risk-taking by pilots by measuring the probability that they are no longer mentioned in the OKL reports, almost always a sign that they had perished or been injured. They found that the probability of such an exit more than doubled for average pilots, those below the 80th percentile, while it hardly increased at all for the best pilots.

The bottom-line findings: When a former squadron peer is mentioned, the very best pilots tried harder, scored more victories, and died no more frequently, but average pilots won only a handful of additional victories and died at a much higher rate than their peers.

Thus, the researchers conclude that positive recognition of an individual can be a double-edged sword within institutions, particularly in high-risk, dangerous professions: "Our results suggest that the overall efficiency effects of non-financial rewards can be ambiguous in settings where both risk and output affect aggregate performance."

—Jay Fitzgerald