WWII Policy Kept Patents Secret, Slowed Innovation

Requiring that select patent applications not be published kept inventions out of enemy hands, but lowered the rate of follow-on discovery.

Since congressional passage of the Patent Act of 1790, the United States has broadly encouraged inventors to disclose their secrets in the belief that the free flow of scientific information would spur future innovations by competitors and other inventors. In exchange, the government has protected inventors' commercial rights for a limited period of time.

During World War II, however, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) ordered patent applicants to keep inventions in more than 11,000 patent applications secret. The idea was to keep war-related inventions out of the hands of America's enemies. The effects of that policy are analyzed by Daniel P. Gross in The Consequences of Invention Secrecy: Evidence from the USPTO Patent Secrecy Program in World War II (NBER Working Paper 25545).

"Compulsory invention secrecy reduced follow-on invention and restricted commercialization, but as part of the security policies in place during the war it appears to have been effective at keeping sensitive technology out of the public view," Gross concludes. "Taken together, the results suggest there are consequences to a compulsory secrecy policy to be weighed against the security concerns."

In 1940, with war raging in Europe, Congress renewed 1917 legislation — originally passed to restrict disclosure of sensitive technology in the First World War — that authorized the USPTO to issue secrecy orders on patent applications and to withhold the grant of a patent if publication might compromise the war effort. Some 11,200 patent applications were targeted. Under threat of loss of patent rights, imprisonment, and $10,000 in fines, inventors were told not to disclose their innovations or to file for patents in foreign countries.

From July 1940 until just after the war, when most of the secrecy orders were lifted and the relevant patents were allowed to be issued, the restrictive policy appears to have achieved the desired effect. The study finds a sharp jump starting in 1945 — when secrecy ended — in the use of technical words from secret patents. But the policy appears to have inhibited follow-on invention.

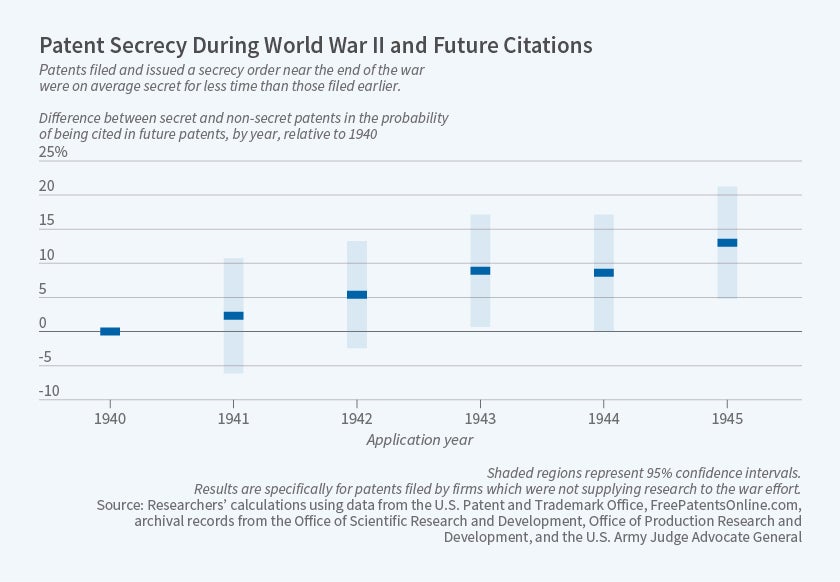

Because the patents targeted with secrecy orders were on average more important inventions than those that were not restricted, comparing all secret versus non-secret patent applications would not provide a clear picture of the effects of secrecy. Instead, Gross compares patents that were filed near the end of the war, and thus had shorter secrecy terms, to patents filed earlier in the war, with longer secrecy terms. He finds that secret patents filed in 1945 were nearly 15 percent more likely to be cited in later patent applications than those filed in 1940 or 1941, relative to non-secret patents of the same vintage and technology area. These effects are weaker for patents filed by firms which were performing R&D for the war effort. Such firms were sometimes — if not often — permitted to share information on otherwise-secret inventions to further contract work. The study also finds some evidence that secrecy may have hindered the commercialization of new inventions.

Secrecy orders are still in use today, under the authority of the Invention Secrecy Act of 1951, and inventors and companies, concerned about imitation or intellectual-property theft, often prefer to keep their discoveries secret rather than patent them. The experience from World War II suggests that such actions may impede technological progress.

— Laurent Belsie