The Impact of High Deductibles on Health Care Spending

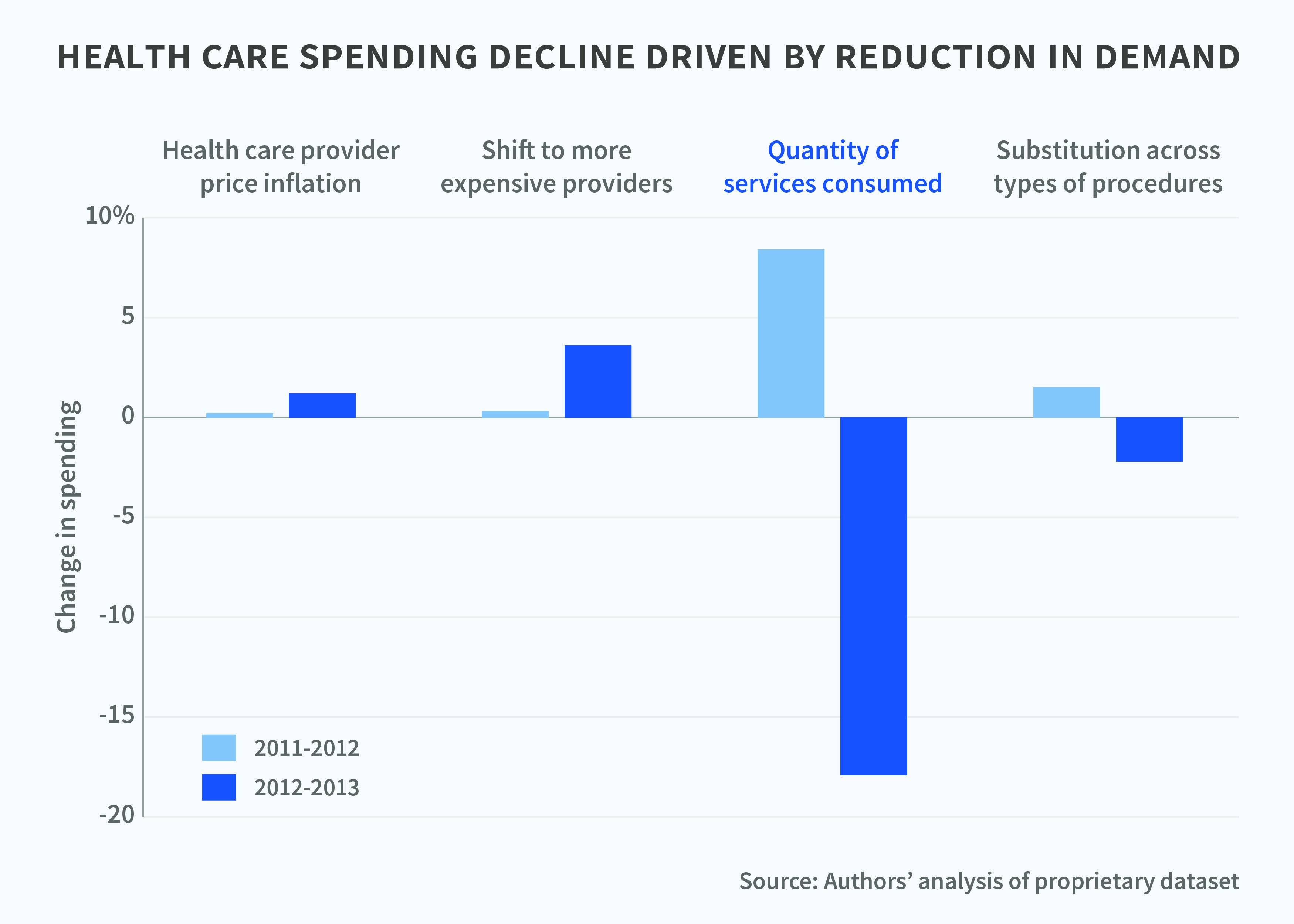

Implementation of the deductible reduced employee health care spending by 12 to 14 percent, nearly all from reduc-tion in demand for services.

After years of providing completely free medical care to its employees, a large company switched to a high-deductible insurance plan that, in its first year, covered 78 percent of expenditures. The subsequent change in the spending patterns of employees suggest that textbook models of rational consumer behavior do not apply to demand for health care.

The patterns are scrutinized in What Does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-Sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics (NBER Working Paper No. 21632) by Zarek C. Brot-Goldberg, Amitabh Chandra, Benjamin R. Handel, and Jonathan T. Kolstad.

The researchers studied individual health records from nearly all the self-insured firm's 35,000–60,000 employees and 105,000–200,000 dependents for six years. Median income was between $125,000 and $150,000. The company implemented the high-deductible plan in the fifth year of the data, but continued to offer employees access to the same broad set of medical providers and services available under the entirely free plan.

After controlling for inflation and demographic changes, the researchers found that the deductible reduced overall employee health care spending by about 13 percent annually, and that some of the services consumers elected to forgo were "likely of high value in terms of health and potential to avoid future costs."

They found that nearly the entire decline resulted from an outright reduction in the consumers' demand for services, rather than from them price shopping or substituting less costly procedures. In fact, there was actually a shift to more expensive providers. This was despite the employees being offered a tool to search for doctors by location, specialties, fees, and other factors, as well as to compare pric-ing of such standardized services as MRIs.

The researchers also found that once individuals spent enough to reach the deductible, their health care spending patterns reverted to pre-change levels. Strikingly, this was even the case among those with a medical history that made it all but certain they would exceed the out-of-pocket maximum. Had they acted like forward-looking consumers, these less-healthy individuals would not have deprived themselves of care while under the deductible. They had no reason to be price-sensitive, since they could have predicted that they inevitably would have reached the stage when their care would be entirely free.

The researchers found that during the deductible phase, demand for services slackened across the board – both for preventive care, which might have saved money in the long run, and for expensive tests of questionable value. Demand also dropped for services that are free under the Affordable Care Act, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, perhaps because individuals were unaware of the benefits because they had avoided the doctor. Another possible explanation is that they feared that the free tests would lead to costly services.

The authors conclude by questioning whether a high deductible may be too blunt an instrument with which to rein in health care costs. They note that even relatively well-educated and well-paid consumers in their data sample appear to act in ways counter to their financial and medical interests.

—Steve Maas