The Rise of High-Skilled Migration from Asia to the US

In 1990, workers from India, China, South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines accounted for 3.6 percent of the US college-educated workforce. By 2019, their share was 7.3 percent, with concentration in the information technology, higher education, innovation, and healthcare sectors.

In From Asia, With Skills (NBER Working Paper 34449), Gaurav Khanna examines the factors driving this migration surge and its economic consequences. The study draws on US Census microdata, American Community Survey data, visa records, Current Population Survey data, and administrative records on international students.

Rising US skill demand and Asia’s education boom fueled high-skill migration, reshaping innovation, universities, and healthcare.

Migrants from these five countries accounted for 38 percent of the growth in US software developers, 25 percent of the increase in scientists and engineers, and 21 percent of the growth in physicians between 1990 and 2019. By 2019, 78 percent of Indian-born and 63 percent of Chinese-born workers in the US labor force held bachelor's degrees, compared to 39 percent of US-born workers.

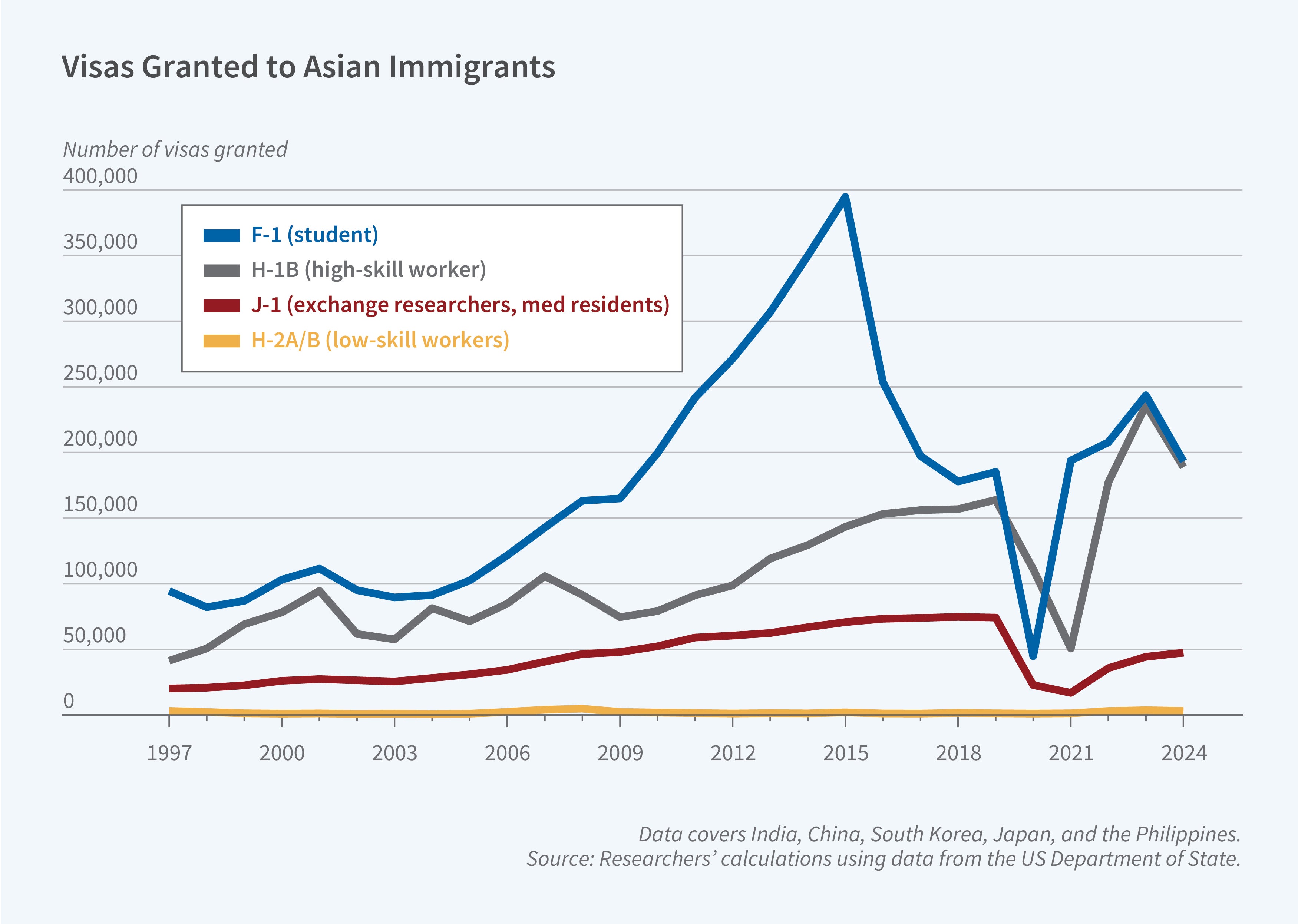

The H-1B visa program, established in 1990 for specialty occupations, became the primary pathway for technology workers to enter the US in subsequent decades. Student visas (F-1s) emerged as an uncapped alternative pathway. Chinese student enrollment surged between 2005 and 2016, followed by rapid Indian student growth after 2014. By 2023, Indian students surpassed Chinese students to become the largest international student group.

Three major demand shocks drove US need for foreign talent. First, internet commercialization in the mid-1990s led to the growth of the tech sector, and expanded computer science employment fourfold from 1 million in 1990 to 4.3 million workers by 2019. Second, state funding cuts to public universities after 2008 prompted institutions to enroll full-fee-paying international students, bringing in much-needed revenue. Finally, an aging US population increased healthcare demand while policy restrictions limited US physician supply. As a result, pathways to immigration for foreign doctors were established, and international medical graduates now comprise over 30 percent of physicians in the lowest-income rural areas, delivering care quality comparable to US-trained doctors.

When US demand for skilled workers rose, Asian countries developed complementary supply advantages. China's tertiary enrollment expanded from 3 percent to 75 percent between 1990 and 2023, while India's grew from 6 percent to 33 percent. China expanded the number of universities from 1,000 in 1999 to 2,900 by 2021, with graduates rising from 1.1 million to 7.9 million. Indian H-1B lottery winners experienced large earnings increases compared to workers who remained in India, providing strong incentive for migration. High-quality STEM institutions and English-language instruction in India created readily transferable skills.

Across occupations, growth in native-born employment and growth in Asian-born employment are positively correlated, a finding that suggests Asian migrants filled expanding positions rather than displaced US workers in most sectors. Supply constraints from policy restrictions in healthcare and rapid technological change in computing may have resulted in worker demand outstripping domestic training capacity.

The foreign-born workers who emigrated from Asia had important economic effects. These immigrants had higher patenting rates than natives and increased innovation at the firms that employed them. By the late 1990s, Chinese- and Indian-born engineers ran one in four tech startups in Silicon Valley. In 2022, 55 percent of US startups valued over $1 billion had immigrant founders. International students, many of whom returned to the US as workers after graduation, contributed $56 billion to the US current account in 2024 through educational services exports.

The effects of emigration on origin countries varied. India's IT sector expanded through "brain gain," whereby migration prospects induced skill accumulation benefiting workers who remained. Binding H-1B caps and lengthy green card processes resulted in many Indian emigrants returning after six years in the US. Return migration rates are relatively high for Chinese, Korean, and Japanese migrants, supporting knowledge transfer and potentially catalyzing the growth of entrepreneurial technology sectors in their countries of origin. The Philippines, which trains nurses for emigration, benefits from remittances from those who are working in the US.