Overlap in Corporate Leadership Increases Collusion

Firms are more likely to agree not to recruit each other's employees if they share the same senior executives or members of their boards. In Collusion Through Common Leadership (NBER Working Paper 33866), Alejandro Herrera-Caicedo, Jessica Jeffers, and Elena Prager analyze information and records that became available in connection with “the largest known case of modern US labor market collusion.” The records came to light as the result of a court case brought against eight Silicon Valley firms by the US Department of Justice in 2010, followed by civil lawsuits implicating several dozen more firms. The information includes email trails and human resource documents that detail “no-poaching” agreements.

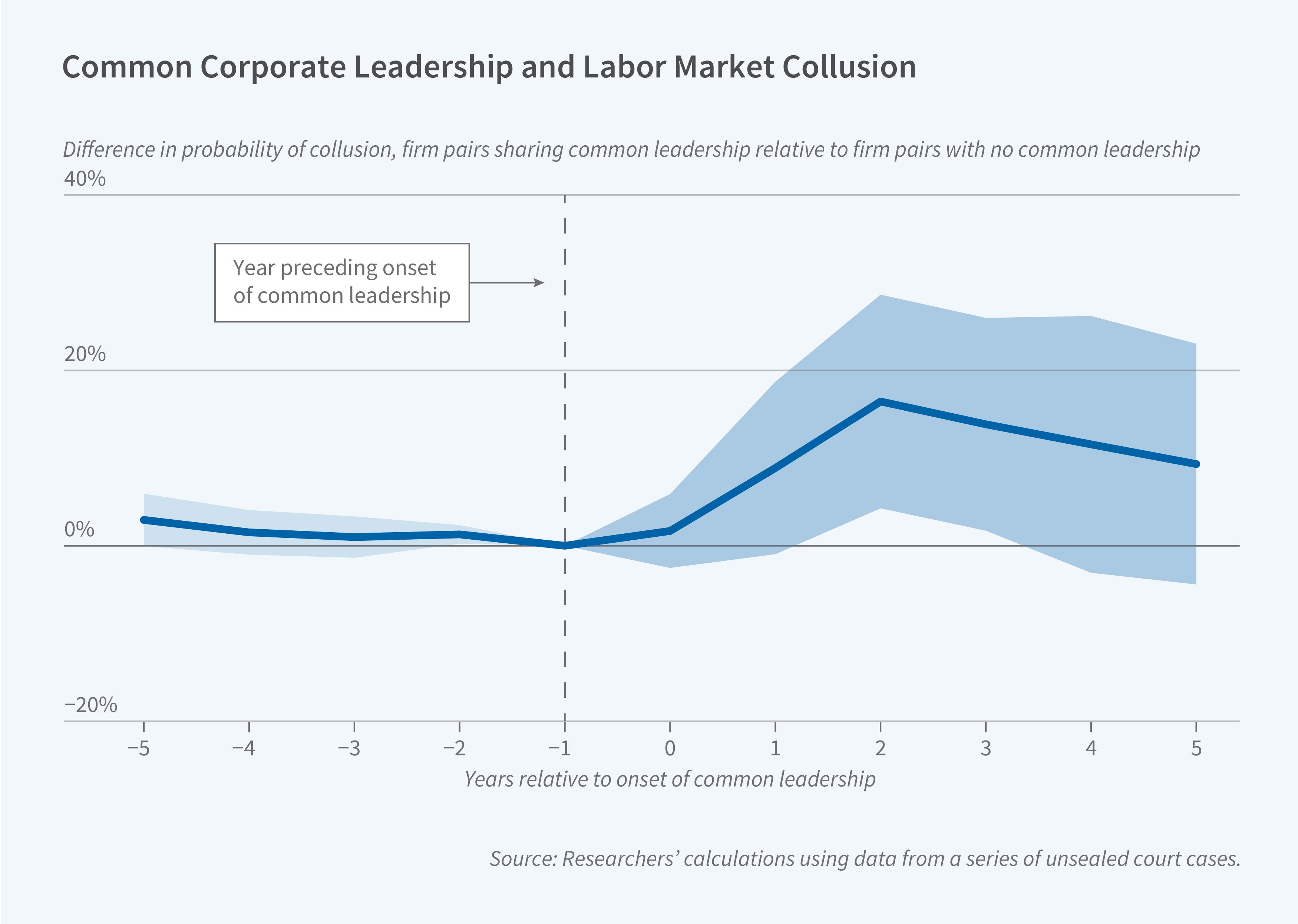

Common leadership between two firms increases the probability of a no-poaching agreement by 11 percentage points.

The behavior that was prosecuted in the cases began in the early 2000s, when tech companies faced a talent shortage. They would “cold call” other firms’ employees with attractive job offers, believing them to be of higher quality than people who had applied for a job on their own. Bidding wars would often ensue, driving up worker compensation generally, not just for the workers being recruited. To avoid this outcome, some firms established no-poaching agreements with their rivals, typically ruling out making unsolicited job offers to any of a rival’s employees. Some agreements went further and proscribed bidding wars even when an employee independently applied for a job at a rival company.

One of the earliest no-poaching agreements was established in 2005 when Apple CEO Steve Jobs asked Google co-founder Sergey Brin to stop recruiting Apple workers. That agreement triggered a wave of pacts that eventually implicated 65 companies. By entering into agreements to not compete for workers, the firms were violating federal antitrust laws. The companies apparently felt that they had little to fear, since historically antitrust laws had rarely been enforced in labor collusion cases.

The researchers’ sample covers 43 colluding firms, 63 percent of which shared a leader with at least one other firm that was in the research sample between 2000 and 2009. For reference, 38 percent of public companies nationwide share a high-level leader with another public firm, often another firm in the same industry. In the study, the probability of adopting a no-poaching agreement rose by 11 percentage points after the onset of common leadership, compared with a baseline rate of 1.2 percent among firms without shared leadership. The probability of establishing a no-poaching agreement peaked two years after the onset of common leadership. Collusion may have been more likely if the shared leaders were executives—and thus more hands-on—than if they were board members. It was more likely if the firms shared labor pools and slightly more likely if the firms had a high degree of common ownership, but it was not related to product market competition.

The researchers conclude that common leaders may serve as a useful flag for competition authorities. Although enforcing the existing prohibition on common leaders may come with other costs, extra scrutiny of competing firms that share leaders is likely to reduce collusion.

- Steve Maas

Elena Prager gratefully acknowledges funding from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.