Wage Compression Drives Nordic Income Equality

Income inequality in the Nordic countries — Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden — is substantially lower than in the United States or the United Kingdom despite similar levels of per capita income. The Gini coefficient for disposable income in Nordic countries averages 0.27, compared to 0.39 in the US and 0.36 in the UK. In Income Equality in the Nordic Countries: Myths, Facts, and Lessons (NBER Working Paper 33444), Magne Mogstad, Kjell G. Salvanes, and Gaute Torsvik analyze the underlying source of these disparities. They employ detailed microeconomic data and statistical decomposition techniques and consider distributional statistics on income, wages, working hours, education, and skills across these countries.

The greater income equality in Nordic countries than elsewhere is primarily the result of wage compression via coordinated collective bargaining rather than redistributive taxation.

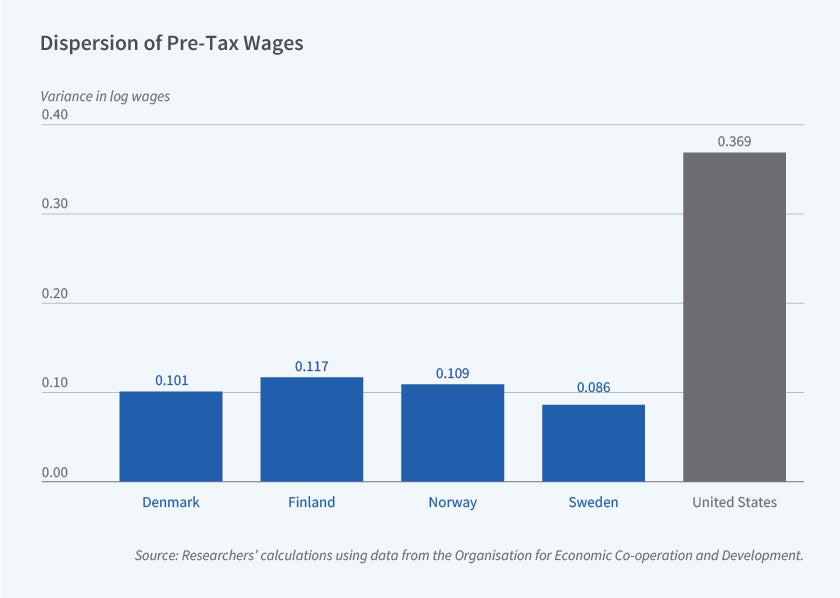

The researchers identify wage compression as the primary driver of Nordic income equality, accounting for about two-thirds of the disparity relative to the US. Hourly wage inequality is significantly higher in the US than in the Nordic countries. The variance of log hourly wages is three times higher and this explains over 70 percent of the difference in earnings inequality. Lower dispersion in working hours and a smaller covariance between hours and wages — high-wage workers work relatively fewer hours in the Nordic countries than in the US — account for the remainder.

Coordinated wage setting through collective bargaining is the key mechanism for wage compression. Nordic countries maintain strong wage coordination both within and across industries, with base wages set through centralized bargaining and supplemental local negotiations. This system compresses the wage distribution relative to labor productivity, particularly benefiting workers in lower-productivity firms and limiting wage premiums in high-productivity firms.

Contrary to popular belief, the Nordic wage compression does not primarily reflect a more equal distribution of skills or education. The distributions of cognitive skills, as measured by standardized tests, and educational attainment are relatively similar in the Nordic countries, the UK, and the US. Instead, the Nordic countries have substantially lower skill premiums. A 1 standard deviation increase in cognitive skills is associated with a 10–12 percent increase in hourly wages in Nordic countries, compared to a 23–24 percent increase in the UK and the US.

The researchers also challenge another common explanation—that Nordic family policies like subsidized childcare and parental leave significantly increase equality by supporting maternal employment and equalizing children’s opportunities. They conclude that public spending on day care, education, and health programs has a relatively limited impact on the distribution of skills and labor market outcomes.

Redistribution through taxes and transfers, while contributing to lower income inequality in Nordic countries, explains only about one-third of the differences in inequality between them and the US.

The researchers appreciate financial support from the Research Council of Norway and National Science Foundation grant 341250.