Healthcare Accreditation and Care in US Jails

With more than 600,000 individuals in jails on any given day and more than 7 million passing through jail at some point during each year, the United States has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world. In a landmark 1976 decision, Estelle v. Gamble, the US Supreme Court ruled that deliberate indifference to the serious medical needs of incarcerated people violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. Individuals who are in jail are the only group to have a constitutional right to “reasonably adequate” healthcare. There is little oversight or funding, however, of healthcare in short-term detention facilities.

In The Hidden Health Care Crisis Behind Bars: A Randomized Trial to Accredit US Jails (NBER Working Paper 33357), researchers Marcella Alsan and Crystal Yang study the effects of medical accreditation on inmates’ health outcomes. Fewer than one in five correctional facilities have sought third-party accreditation.

Healthcare accreditation of US jails reduces mortality rates and recidivism.

To study the impact of accreditation, the researchers recruited 44 small and midsize jails across the country and then provided subsidies to encourage half of them to obtain accreditation. Over the course of the four-year study, 13 facilities were accredited by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC). From the initial sample, 22 facilities received more modest subsidies; they served as the control group and started accreditation at the end of the study.

The researchers gathered data and feedback from the jails’ leadership, custody and medical staff, outside jail administrators, healthcare providers, and former inmates. They also examined independent audits of the facilities’ medical records and death logs. They found that the offer of accreditation led to statistically significant and economically meaningful benefits for a range of outcomes.

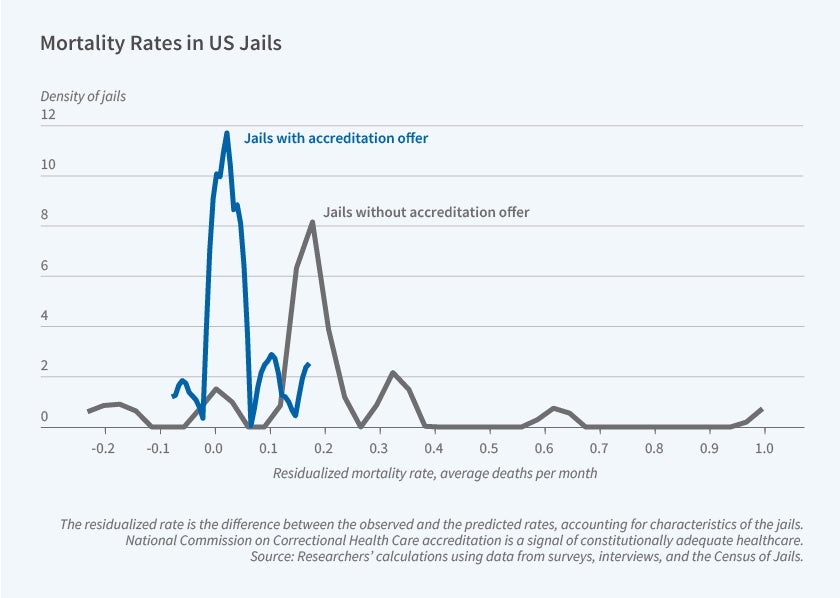

Inmate mortality in the facilities that were offered accreditation was only one-third as high as that in the control group. The treatment facilities also showed more effective coordination between custody and medical staff. Treatment facilities observed custody staff trained in law enforcement began to work with the medical staff to allow screening and initial health assessments within the first few days of incarceration, when people are most at risk. The researchers found medical and custody staff coordination rose by 4.7 percentage points, an increase of 7 percent relative to the control group. Staff satisfaction rose 2.8 percentage points, even though jails did not add staff or make large capital investments during or after the process. Jails with fewer medical personnel per inmate saw larger reductions in mortality and improvements in compliance with quality standards. Compliance with “personnel training” and “patient care and treatment” also improved by 15 percent and 11 percent, respectively, relative to the mean of the control group.

The offer of accreditation was associated with a reduction in recidivism. Individuals released from treatment facilities were 44 percent less likely to be rebooked at the same jail in the following three months and 45 percent less likely within six months than those released from control facilities. This improvement could prove cost-effective since a lower rate of recidivism implies greater public safety and smaller jail populations.

— Laurent Belsie

The researchers gratefully acknowledge funding from J-PAL North America, the William T. Grant Foundation, the Preparedness and Treatment Equity Coalition, Arnold Ventures, and the Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School.