The Trajectory of US Unemployment After World War II

In Why Didn’t the US Unemployment Rate Rise at the End of WWII? (NBER Working Paper 33041), Shigeru Fujita, Valerie A. Ramey, and Tal Roded investigate why the postwar unemployment rate rose just a few percentage points despite the dramatic decline in US government spending. Using aggregate and sectoral data, government surveys, and a new longitudinal dataset on thousands of individuals spanning the 1940–1950 period, they explore how the US economy was able to reallocate workers so quickly and the factors that led to robust job creation despite the significant fall in military spending.

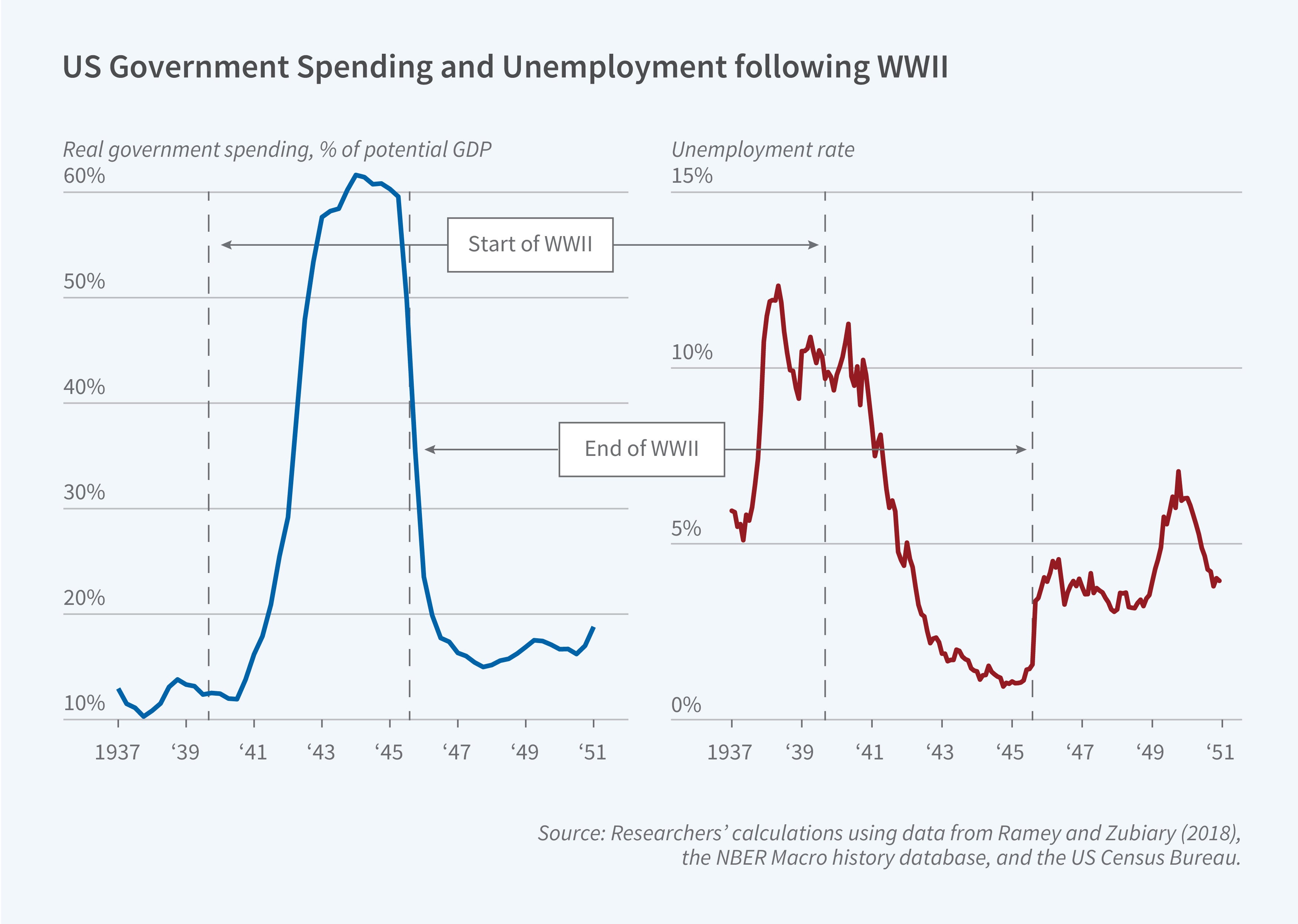

Despite forecasts of a deep recession associated with a massive drop in government spending following the end of World War II, US unemployment rates rose just a few percentage points.

The researchers find that labor force withdrawals among females aged 20–44 and male war veterans contributed to the modest unemployment rise. Using data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Reports (the precursor to the Current Population Survey) and other sources, they document large drops in labor force participation after the war for young adults. Many veterans took extended vacations after their discharge, and many enrolled in school. These two reasons explain the entire decline of men’s labor force participation. Surveys asking individuals why they left the labor force reveal that women aged 20–44 were more likely “pulled” out of the labor force by home production than “pushed” out by returning male veterans.

Most of the workers who stayed in the labor force and were separated from their jobs moved directly into a new one. Workers often accomplished these job-to-job transitions by moving across industries. For military discharges, armed forces to civilian employer movements were the most important, but movements out of the labor force were also sizable. The findings are an important demonstration that large reallocations of workers across sectors do not always lead to high unemployment rates. In examining the occupational mobility of workers, the researchers find that returning veterans quickly returned to their previous position on the occupation ladder, whereas those laid off from civilian jobs experienced a significant step-down.

The high rate of transition between jobs was only possible because new jobs were being created. At the time, experts worried the economy would fall back into depression once the war stimulus evaporated. Yet, the economy boomed as private demand for goods and services filled the gap. Possible explanations include pent-up consumer demand facilitated by wartime saving and the Federal Reserve’s low-interest-rate policy. The researchers uncover another mechanism through which WWII sowed the seeds of the postwar boom: High government spending during the war crowded out investment in housing, consumer durable goods, and business capital, resulting in depressed levels of private capital stocks by the end of the war. When military spending fell, basic market forces caused private investment to surge as consumers and firms sought to bring capital stocks up to the balanced growth path.

— Lauri Scherer

Valerie Ramey gratefully acknowledges financial support from National Science Foundation Grant No. 1658796.