Health Effects of Cutting Air Pollution in US Coastal Waters

Maritime shipping emits half as much fine particulate matter as global road traffic. A decade ago, the United States in conjunction with the International Maritime Organization (IMO) issued new regulations to limit the emissions of oceangoing vessels. As a result, particulate pollution has fallen substantially in areas along US coastlines. In Uncharted Waters: Effects of Maritime Emission Regulation (NBER Working Paper 30181), Jamie Hansen-Lewis and Michelle M. Marcus study the impact of these regulations on health outcomes that have previously been found to be sensitive to pollution levels, as well as on the behavior of ship operators.

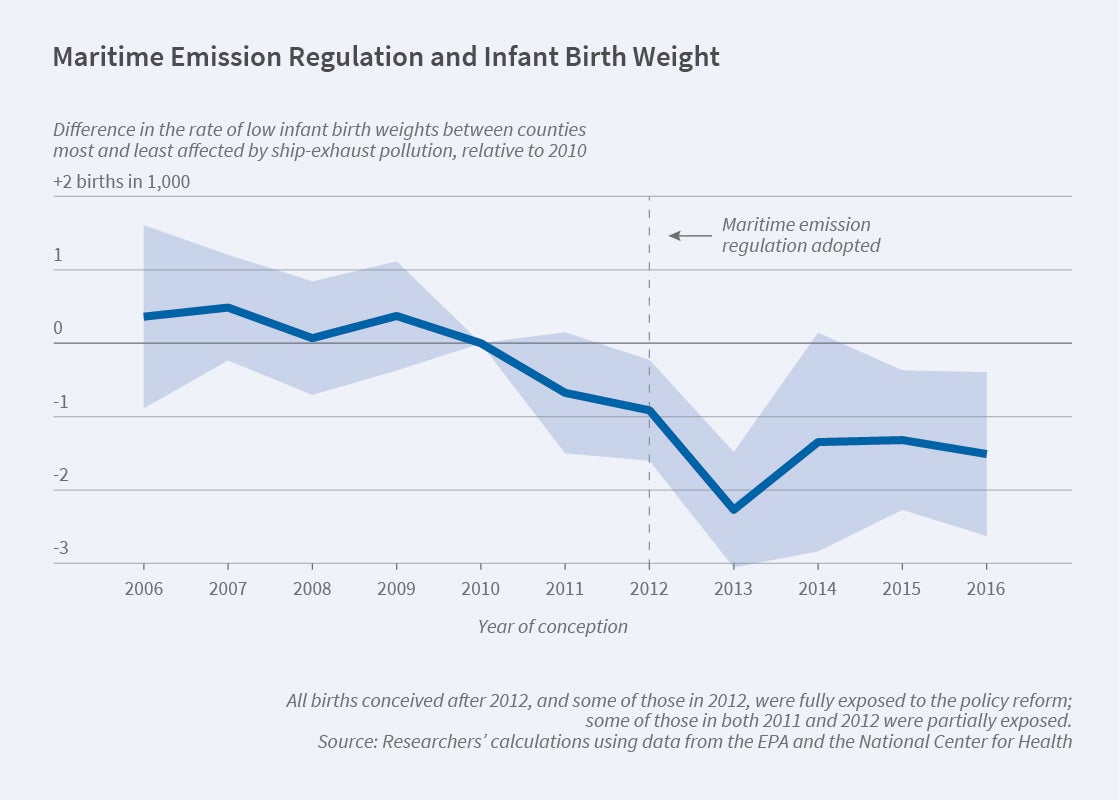

In 2012, the US created emission control areas (ECAs) where commercial ships are required to use expensive less-polluting fuel when within 200 nautical miles of the coast, or are required to install abatement equipment. The study finds that the ECAs cut the population-weighted average of fine particulate matter in counties near heavy ship traffic by 4 percent. This decline in fine particulate pollution coincided with a drop in the number of low birth weight babies of 1.7 percent on average in affected areas. Infant mortality decreased by 3.5 percent. The researchers estimate the new regulations led to 1,536 fewer instances of low birth weight and 290 fewer infant deaths annually. This reduction in infant mortality, when valued using estimates of the value of a statistical life that are used by some US federal agencies, yields a monetary value that is close to the regulations’ estimated cost of $3.2 billion.

US regulations requiring ships within 200 nautical miles of shore to limit particulate emissions are associated with lower infant mortality and fewer instances of low birth weight.

The study finds that the regulations only reduced ambient particulate levels by half as much as they were expected to. This could be due to a number of factors. For example, some ships changed their routes to avoid using the costlier fuel specified by the regulations. In addition, in some areas, the coverage of the ECAs is limited by national boundaries. Since Mexico does not have ECAs, portions of US states near it — such as California and Texas — have ECAs that are narrower than the 200 nautical mile standard. South Florida’s ECA is narrower because of its proximity to the Bahamas and Cuba. In US counties with an ECA boundary of less than 200 nautical miles, the reduction in particulates was about half of that experienced in counties with the full 200 nautical mile buffer. Counties far below the regulatory threshold for pollution levels saw smaller air-quality improvements than those at high risk of triggering penalties. The researchers hypothesize that those low-risk counties eased their efforts to control land-based emitters since they were unlikely to hit emission limits.

The researchers also suggest that individuals may have changed their behavior in response to the creation of ECAs, spending more time outdoors and thus exposing themselves to more particulates. Using a national activity database of individuals in counties near heavy ship traffic, the researchers find that the more the air quality improved, the more time they spent outdoors.

—Laurent Belsie