The Changing Composition of Sovereign Debt Holdings

National governments that finance their activities by issuing debt must find someone to buy it. The interest rate they must pay to borrow depends on the cost of attracting new buyers, a cost that generally rises along with the outstanding stock of debt. Due in part to government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, the aggregate government debt-to-GDP ratio is now at its highest level since 2003. Outstanding government debt now exceeds GDP in advanced economies, and is greater than half of GDP in emerging economies.

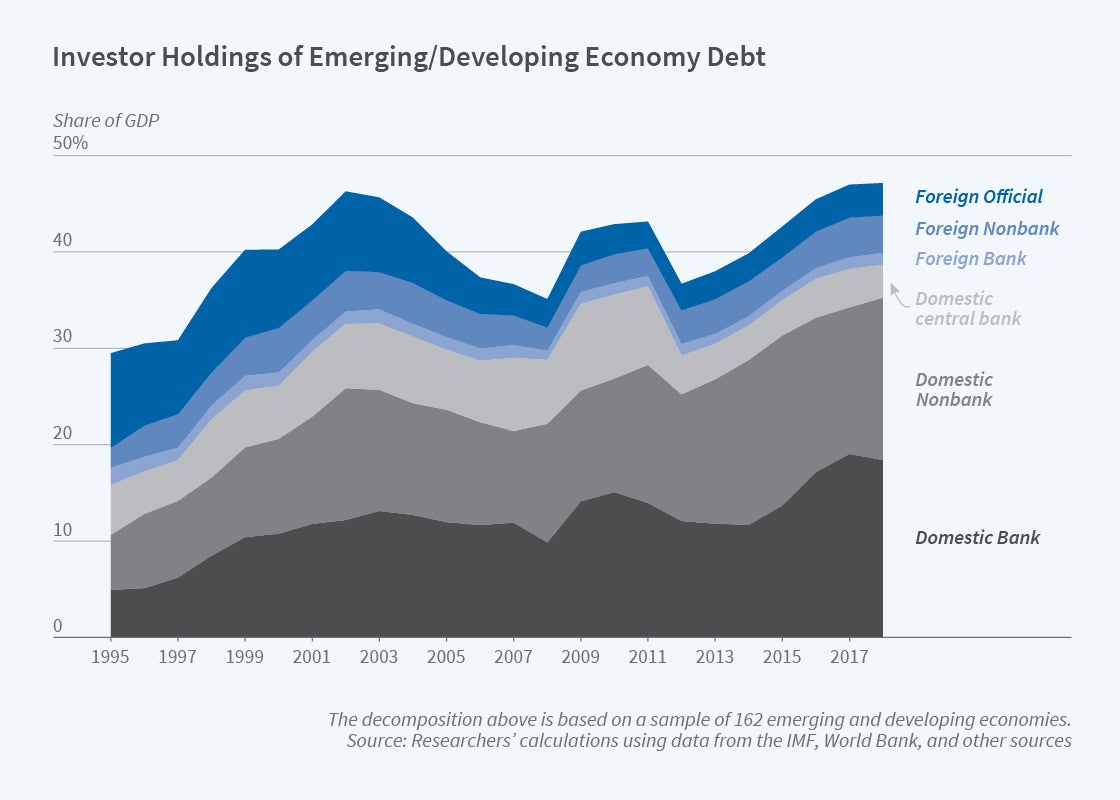

In Who Holds Sovereign Debt and Why It Matters (NBER Working Paper 30087) Xiang Fang, Bryan Hardy, and Karen K. Lewis use International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and Bank for International Settlements data to calculate who holds sovereign debt issued by 95 countries from 1991 through 2018. They divide holders of debt into foreign and domestic investors, and then subdivide those groups into three types of investors: private banks, nonbank private investors, and official creditors. Nonbank private investors include organizations such as pension funds, insurers, endowments, mutual funds, hedge funds, corporations, and households. The official creditors group includes central banks and supranational agencies such as the World Bank and the IMF. Domestic central banks are the official creditors in the domestic investor group.

Nonbank private investors have become increasingly important holders of government bonds.

The overall cost of borrowing depends on a country’s stock of outstanding debt and the responsiveness of investor groups to the debt level and other country-specific circumstances. Combining all emerging markets and all years in their dataset, the researchers estimate that an increase in sovereign debt of 1 percent of GDP raises borrowing costs by about 1.4 percent. For example, an emerging market that expands debt by 10 percent of GDP and currently pays 8 percent on current debt would see its costs rise to 9 percent (8 percent x 1.14).

The data suggest that private nonbank investors are important marginal investors. Over the full sample period being studied, nonbank investors acquired 69 percent of variations in sovereign debt, although they held only 46 percent of all outstanding sovereign debt on average. Banks absorbed just 20 percent of new debt, while holding 28 percent of all outstanding debt.

The composition of debt ownership evolved over the sample period. Government debt held by domestic investors decreased for advanced economies and increased for emerging market economies. Estimated buyer responses differed for debt issued by advanced and emerging economies. Responses to yield increases in developed-economy sovereign debt markets other than the US suggested that the banking sector’s demand for debt is primarily for purposes of liquidity and capital market regulation. Central banks buy advanced economies’ debt to hold as foreign reserves.

Foreign nonbank investors, followed by their domestic counterparts, were most sensitive to changes in advanced-country sovereign debt yields. For advanced economies in which sovereign debt is considered a safe asset, it appears that expansions of government debt do not meaningfully raise financing costs. All investor groups bought more advanced-economy sovereign debt when a country’s export-to-GDP ratio increased, and none were sensitive to currency depreciation.

In emerging economies, foreign nonbank investors increased estimated sovereign debt demand by 1.7 percent when yields increased by 1 percent. Domestic banks’ and nonbanks’ demand increased by about 0.6 percent, and foreign private banks’ demand rose by about 0.5 percent. This implied that if an emerging market sovereign lost its foreign nonbank investors, its borrowing costs could rise because it would be relying on less price-sensitive investors, which would require higher yields.

— Linda Gorman