The Distribution of Paycheck Protection Program Funds

The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) was one of the largest measures undertaken by the federal government to protect businesses and their employees from the adverse economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was authorized by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act in March 2020, and administered by the Small Business Administration (SBA). PPP guaranteed about $800 billion in low-interest loans made by financial institutions to businesses with up to 500 employees, promising to forgive those loans if borrowers maintained employment.

Almost from the program’s beginning, questions were raised about who was getting the loans and whether the distributions were fair. Answering these questions is challenging, however, because of a lack of data on eligible firms and their owners. In Racial Disparities in the Paycheck Protection Program (NBER Working Paper 29748), Sergey Chernenko and David S. Scharfstein offer a solution by studying the take-up of PPP loans by Florida restaurants. This enables the researchers to determine the racial and ethnic identity of the owners of a population of eligible firms for which they have detailed firm characteristics. They match data from restaurant licenses, corporate records, voter registrations, and Yelp to records from the PPP and the COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program, which was also administered by the SBA and offered long-term, low-interest loans to firms adversely affected by the pandemic. Unlike the PPP, EIDL loans were not forgivable and, crucially, firms applied directly to the SBA for approval, rather than to an intermediary such as a bank.

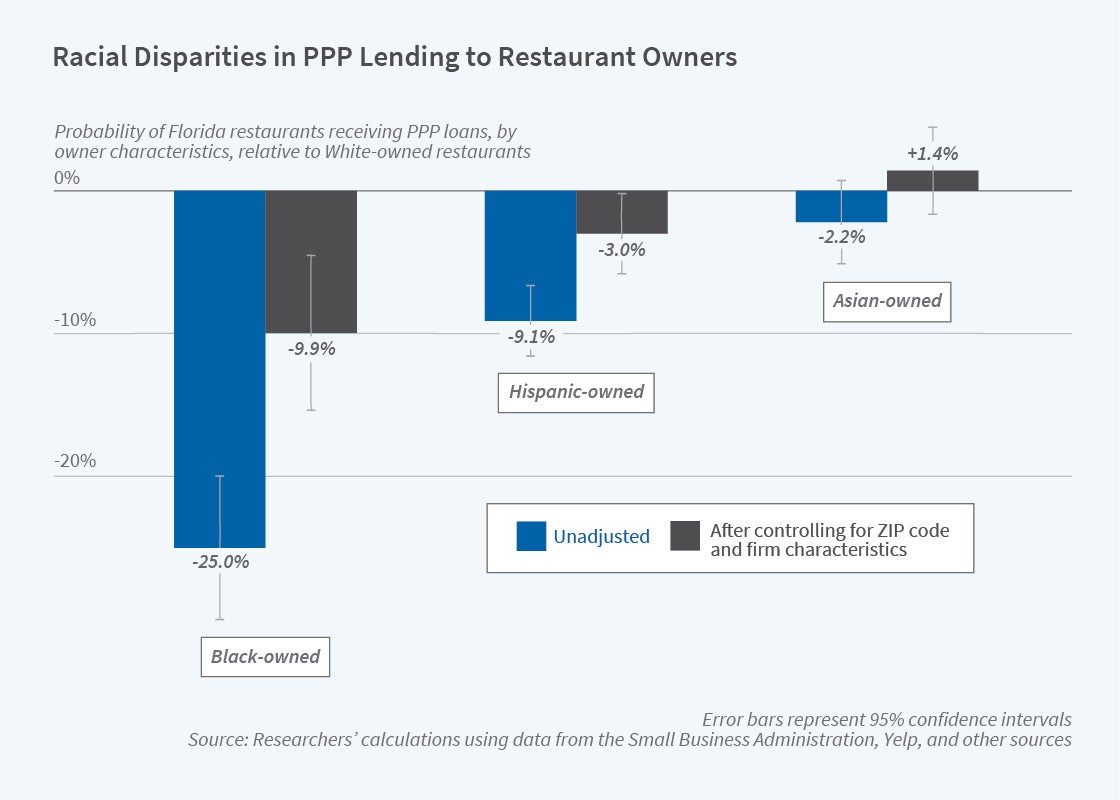

Black-owned restaurants in Florida were 25 percent less likely, and Hispanic-owned restaurants 9.1 percent less likely, to receive PPP loans than their White-owned counterparts.

The researchers find that Black-owned restaurants were 25 percent less likely to receive PPP support than their White-owned counterparts. Hispanic-owned restaurants were 9.1 percent less likely to receive PPP loans than White-owned establishments. Disparities in overall PPP borrowing were driven by disparities in bank borrowing. Black-owned restaurants were 33.6 percent less likely than White-owned restaurants to receive PPP loans through banks, and Hispanic-owned restaurants were about 10 percent less likely. Some of the disparities were offset by greater borrowing from nonbank PPP lenders — mostly fintechs. These disparities did not exist in the EIDL program; if anything, minority-owned restaurants, particularly Hispanic-owned ones, were more likely to receive EIDL loans.

The researchers examine a variety of factors that could explain the lower rates of bank PPP borrowing by Black- and Hispanic-owned restaurants. Location accounted for 20–30 percent of the disparity: restaurants in ZIP codes with fewer bank branches per capita, lower household income, and more COVID cases per capita — all attributes of minority neighborhoods — were less likely to get PPP loans. Restaurant characteristics, gleaned from Yelp, accounted for another 40 percent of the disparity: older, larger, and more heavily visited and reviewed restaurants, which tended to be White-owned, were more likely to receive PPP funding.

The researchers also present evidence that racial bias contributed to the observed disparities. Using data collected by Project Implicit on explicit and implicit racial bias across Florida counties, they note that an increase of one standard deviation in the measure of explicit bias in a county was associated with a 13.9 percent decline in the likelihood that a Black-owned restaurant received a PPP loan from a bank. Black-owned restaurants in counties with greater racial bias were much more likely to substitute to PPP loans from fintechs. The researchers point out that while it is possible that racial bias directly affected the application process for Black-owned businesses, it is also possible that a history of poor treatment by banks in more racially biased counties dissuaded Black-owned firms from even applying to banks.

Finally, the researchers show that their results apply not just to restaurants but to firms in all industries. To measure the take-up of PPP loans by firms in other industries, the researchers study firms that received EIDL Advance grants, a sample of firms that were likely aware of the PPP and eligible for the program. The researchers find that, as in the sample of restaurants, disparities were driven by disparities in bank borrowing, and that location, firm characteristics, and racial bias were also important.

— Brett M. Rhyne