The Impact of Competitive Bidding in the Medicare Program

Replacing administratively set pricing with a bidding mechanism reduced spending on 12 durable medical devices by 41.8 percent, and reduced average quantities purchased by 9.3 percent.

In 2020, the Medicare program provided health coverage for 62 million elderly and disabled Americans at a cost of more than $800 billion. Annual expenditures are projected to reach about $1.6 trillion by 2028. Medicare fee-for-service plans cover 60 percent of Medicare beneficiaries. When patients in these fee-for-service plans receive care, Medicare reimburses providers directly at administratively determined reimbursement rates set by complex regulations.

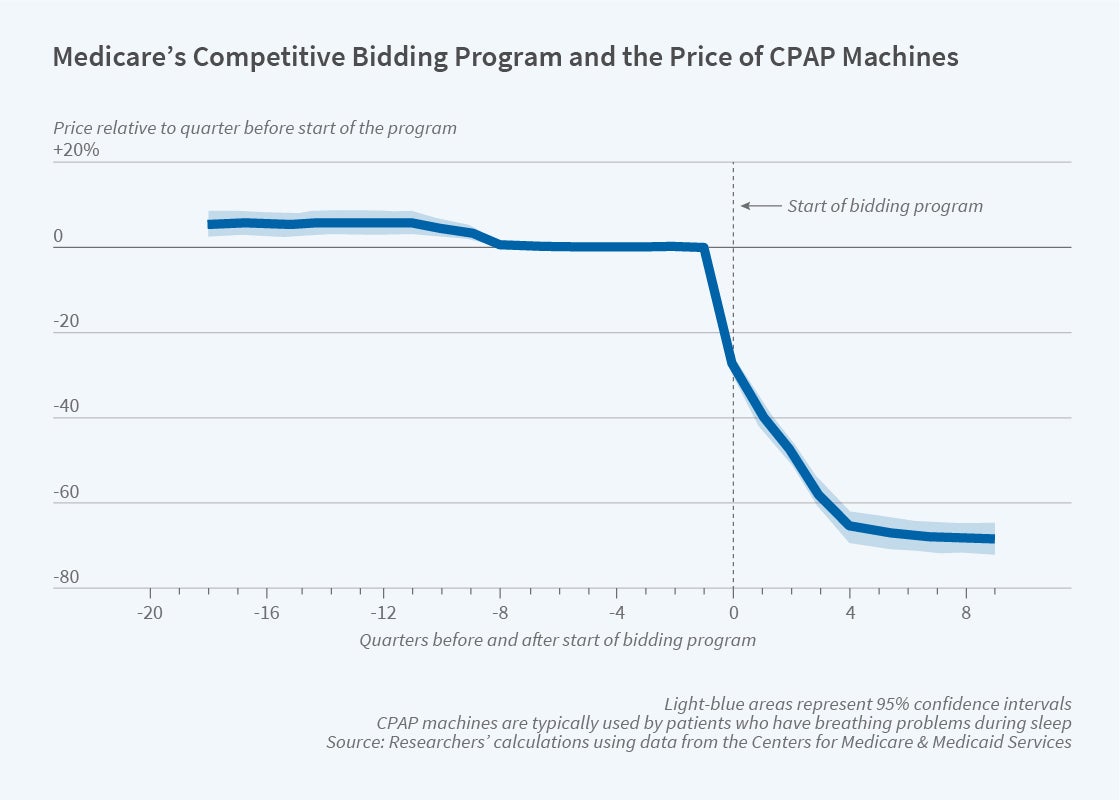

Spurred by concerns that Medicare’s administered prices for durable medical equipment were sometimes higher than market rates, in July 2010, Medicare piloted a competitive bidding program for selected high-cost, high-volume, durable medical equipment products in nine competitive bidding areas. Competitive pricing took effect in the first quarter of 2011.

At the time, Medicare spending on durable medical equipment was $11.3 billion. More than 11 million Medicare beneficiaries had one or more claims for one of the hundreds of items like oxygen concentrators, wheelchairs, CPAP devices, walkers, and infusion pumps that comprise the durable medical equipment category. In 2013, the competitive bidding program was expanded to include 100 additional competitive bidding areas as well as more items. In Getting the Price Right? The Impact of Competitive Bidding in the Medicare Program (NBER Working Paper 28457), Hui Ding, Mark Duggan, and Amanda Starc determine that replacing administered pricing even with “a highly imperfect bidding mechanism” reduced spending on 12 durable medical devices by 41.8 percent. This was mostly due to falling prices; quantities purchased fell 9.3 percent.

The results are based on claims data from a nationwide sample of 20 percent of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. The sample includes claims from the first quarter of 2009 through the fourth quarter of 2015. The analysis exploits the staggered introduction of competitive bidding across time and geographic locations.

To understand the drivers of reduced spending, the researchers perform a detailed examination of spending on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices used to treat sleep apnea. After competitive bidding was introduced, average Medicare spending on CPAP devices fell by 47.2 percent. Prices fell by 45 percent and quantity fell by 4.3 percent at the onset of competitive bidding.

Unless they purchase Medigap insurance, standard fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries have a 20 percent copay for CPAP machines. Those covered by both Medicare and Medicaid have low or no copayment requirements. The researchers separate supply and demand responses by comparing how standard Medicare beneficiaries and dual eligible beneficiaries responded to lower CPAP prices.

They find that demand for CPAP machines was downward sloping for standard Medicare beneficiaries, and that a $1 reduction in out-of-pocket costs led to a 1.73 percent increase in the quantity demanded. Despite lower prices from competitive bidding, fewer CPAP devices were purchased for dual eligible beneficiaries. This quantity reduction suggests that suppliers responded to reduced CPAP reimbursement by reducing supply.

The researchers also construct a measure of clinical appropriateness for CPAP treatment and find that the reduction in CPAP purchase quantity was significantly higher among patients without a formal sleep apnea diagnosis. This suggests that utilization declined most among those who derived less benefit from CPAP use. Calculations using incremental cost-effectiveness ratios from the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence suggest that the savings from the reduction in Medicare spending exceeded the estimated welfare costs of reduced CPAP access.

The researchers conclude that the competitive bidding program reduced prices and spending. The results suggest that Medicare’s future funding challenges could be partially addressed through use of market mechanisms for price setting. They caution that their analysis is not a complete welfare analysis and does not account for supplier profits or the long-term effects of the increased market concentration that accompanied the switch to competitive bidding.