Effects of College Merit Scholarships on Low-Income Students

Full scholarships to low-income high school graduates in Nebraska raised college enrollment and completion, especially for those with the least academic preparation and greatest family disadvantage.

The goal of most financial aid programs is to increase educational attainment for prospective students who might not otherwise be able to enroll in college or to complete a degree. In Marginal Effects of Merit Aid for Low-Income Students (NBER Working Paper 27834), Joshua Angrist, David Autor, and Amanda Pallais measure the impact of a Nebraska program that provides students from low-income families with full scholarships to public colleges and universities. Unusually for research of this sort, the study relies on a randomized controlled trial.

Each year, the Omaha-based Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation (STBF) provides scholarships to thousands of economically disadvantaged students who are judged to be capable of college-level work. To assess the program’s impact, the foundation partnered with the researchers to randomize aid awards to 3,700 high school seniors between 2012 and 2016, and to track their subsequent educational attainment. Each award covered tuition and books for up to five years at any Nebraska public four-year institution, and for up to three years at any Nebraska two-year college. With funding provided by STBF, the researchers tracked the progress of those who received aid awards, and of those who did not, through the educational system.

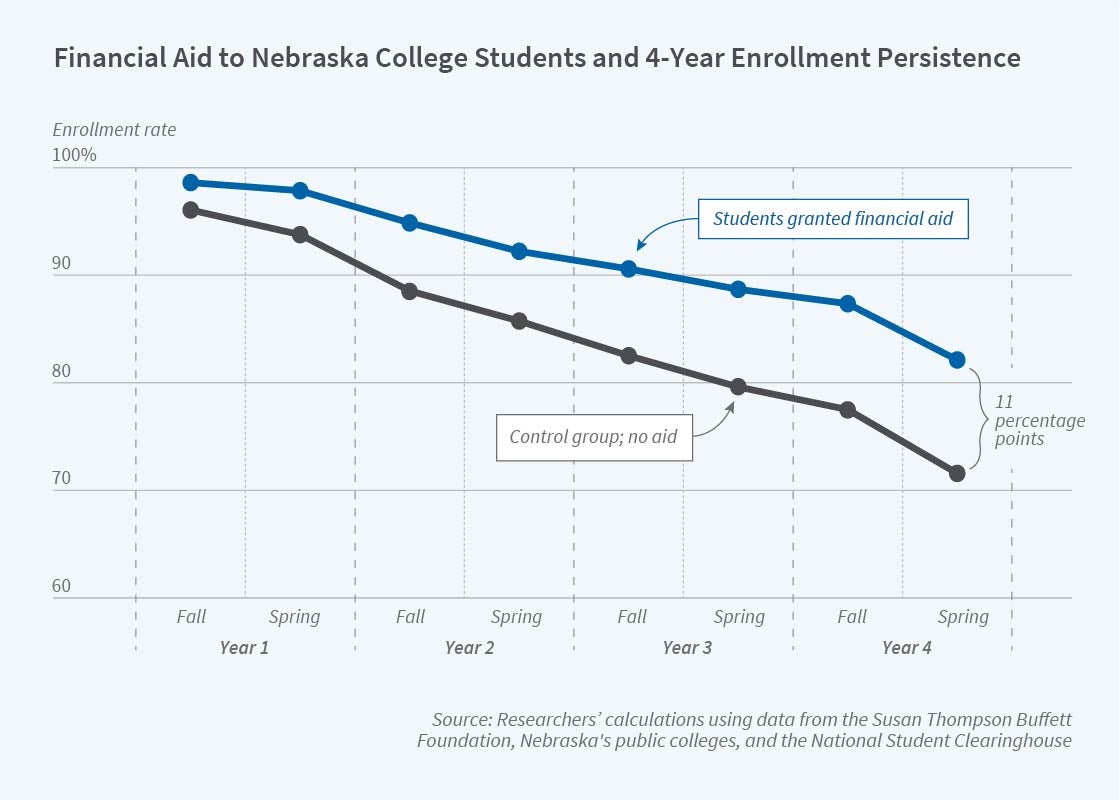

The study found that award recipients enrolled in four-year degree programs at higher rates and were less likely to drop out than those in the randomly selected control group. Among those who said they were targeting four-year degree programs, awards increased bachelor’s degree completion by 8.4 percent, relative to the mean of 63 percent for the control group that did not receive aid. Conversely, awards made to applicants who planned to seek a two-year degree did not increase their likelihood of earning that degree.

Across the board, awardees from groups that are on average less well-prepared for college-level work, including those with relatively low ACT scores and GPAs, enjoyed the largest scholarship-induced boosts in degree completion. Conversely, academically well-prepared students from somewhat higher-income families saw little increase in degree completion, though they finished college with substantially less debt. Students who aspired to attend the University of Nebraska at Omaha — which serves a mostly low-income, disproportionately non-White population that is less likely to enroll in a four-year college without comprehensive financial aid — saw larger-than-average degree gains, on the order of 15 percentage points.

One clue as to why the scholarship worked is that it appears to spur students to engage full-time with a four-year program in their first year of college. Specifically, the effect of the award on ultimate degree completion is almost perfectly predicted by its impact on the number of credits earned in the first year of college.

Although the lion’s share of program spending flows to applicants whose degree attainment is relatively unaffected by the scholarships, the value of college completion for those who are affected is so large that the program passes a simple cost-benefit test for many applicant groups. For low-income, non-White, urban, first-generation, and academically less-prepared students, the award-induced gains in projected lifetime earnings substantially exceed scholarship costs.

— Brett M. Rhyne