Engineers and the Industrial Revolution in 19th Century Britain

Why the Industrial Revolution succeeded in generating sustained economic growth has long been a subject of analysis and discussion. The burst of innovation that took place in Britain in the late 1700s had historical precedents, but they all petered out without producing a dramatic economic transformation.

In The Rise of the Engineer: Inventing the Professional Inventor during the Industrial Revolution (NBER Working Paper 29751), W. Walker Hanlon finds that sustained technological progress was made possible by changes in the way innovation and design work was done in Britain. He identifies the emergence of the engineering profession as a key contributor to this change.

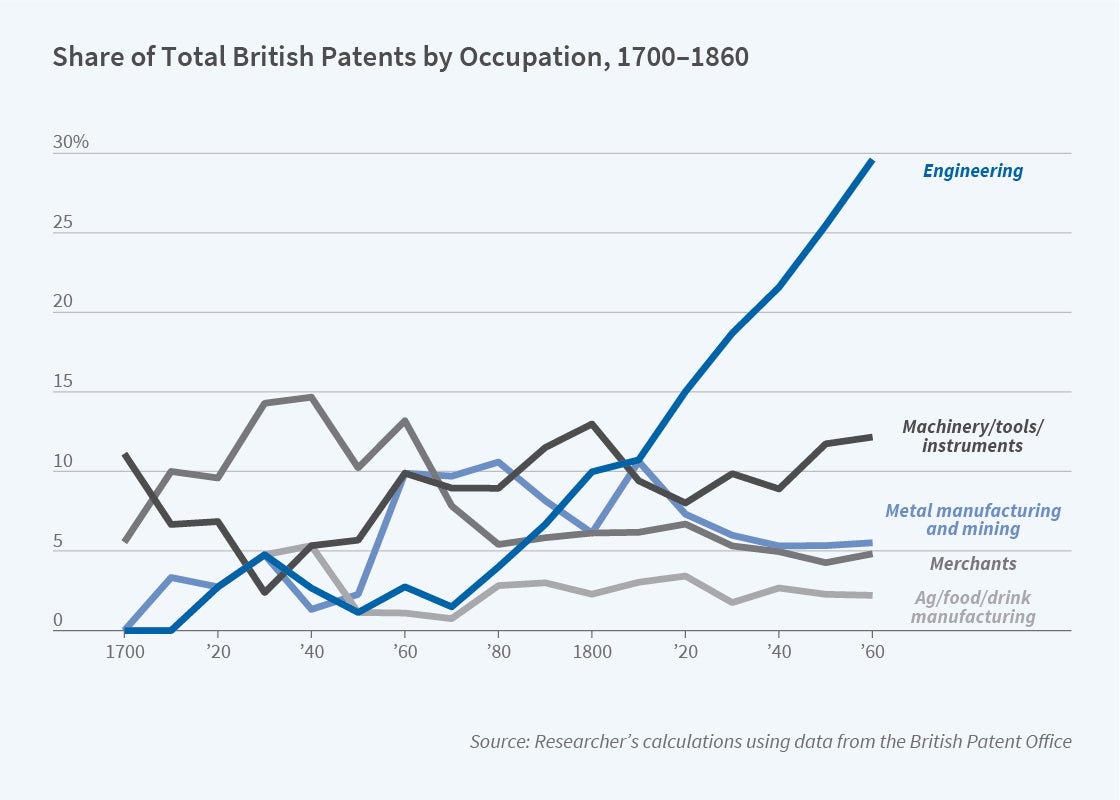

Biographical and patent data show sharp increases in the share of inventions and patents attributed to engineers in the early 1800s.

To study the occupational functions that defined the early engineering profession, Hanlon employs both a qualitative analysis of historical writings and a quantitative textual analysis of information from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Examining the biographies of all 439 engineers in the Dictionary who were born before 1850, he finds the 20 verb stems most closely associated with engineers. “Design,” “invent,” and “patent” are some of the most common activities associated with engineering, indicating the centrality of invention to the new occupation; “build,” “erect,” “employ,” “lay,” and “supervise” indicate implementation. “Consult,” “report,” and “survey” reflect other functions of early engineers. He finds little change in these defining characteristics between 1750 and 1850.

The biographical data also indicate a dramatic increase in the number of engineers during that period. By 1850, engineers made up more than 2 percent of all of those who merited a biography, and around 20 percent of all biographies associated with science or technology.

Since reproducible inventions are widely considered to be central to driving economic growth, Hanlon examines the complete British patent records of 1700–1869, compiles data on just over 8,300 inventors, and groups them into broadly related occupations. In the first decade of the 19th century, an engineer was listed as an inventor on 10 percent of patents. By the 1840s, the share of patents associated with engineers had doubled, and by the 1860s, it had tripled. The overall number of patents also grew sharply over this period. By the 1860s, engineers produced far more patents than any other occupational group. They also patented across a substantially broader set of technology categories than any other type of inventor.

The patent data also show that engineers were fundamentally different from most other types of inventors: they were more productive, their patents were of higher quality, they worked with more coinventors, and they generally achieved greater overall career success.

Hanlon also considers how civil engineering — the field perhaps most closely associated with the engineering profession — professionalized after 1750. He constructs a dataset of 338 major British civil engineering projects, most of which were undertaken between 1600 and 1830. After 1750, these projects were increasingly overseen by experienced engineers at established firms that undertook numerous major projects. These experts also trained the next generation of civil engineers, most of whom gained extensive experience working for established firms before being awarded major projects of their own.

Hanlon offers a theory of how the professionalization of invention by engineers contributed to the acceleration of economic growth during the Industrial Revolution. He emphasizes the process through which new technologies are developed, and argues that specialist researchers — in this case, engineers — are more productive at generating new technologies than nonspecialists. This framework integrates Adam Smith’s insight that specialization can increase productivity in the development of new inventions and designs into a workhorse model of endogenous economic growth.

— Brett M. Rhyne