How Knowledge of Salary History Affects Wage Offers and Hiring

In 21 states, employers cannot ask job candidates about their salary histories, but employers can nonetheless make inferences based on whether candidates voluntarily disclose them.

In response to claims that historical salary differences related to race, gender, or ethnicity may be perpetuated when job applicants are asked to disclose their salary histories, 21 US states have made it illegal for employers to ask prospective employees about their prior compensation. Job applicants in these states may voluntarily disclose previous earnings. Prospective employers may draw conclusions about candidates’ unobserved attributes and outside options based on whether they make such disclosures.

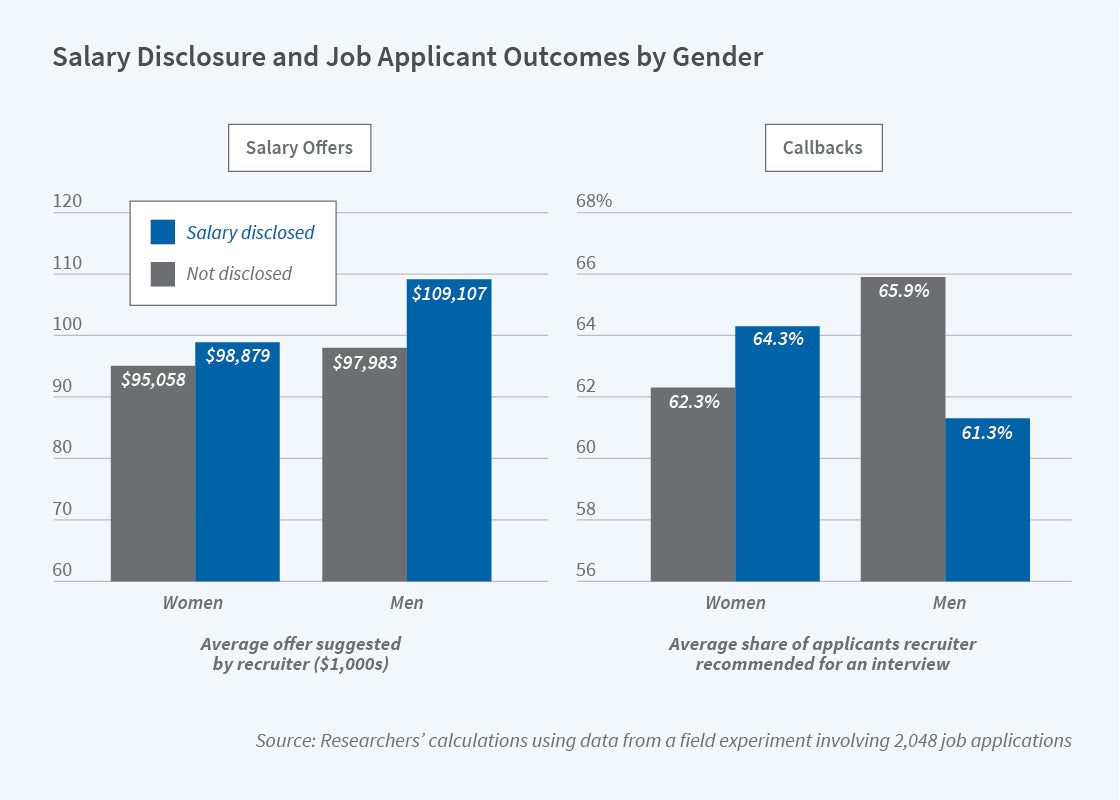

In Salary History and Employer Demand: Evidence from a Two-Sided Audit (NBER Working Paper 29460) Amanda Y. Agan, Bo Cowgill, and Laura K. Gee study how information on an applicant’s salary history shapes wage offers and hiring in the labor market for software engineers. They find that not disclosing salary history decreases salary offers for both men and women.

The researchers created 2,048 fictional job applications based on typical characteristics of software engineering candidates. All applicants were college graduates from roughly equivalent schools with four to six years of experience at well-known firms. Biographical details such as gender, employment at different firms, and whether applicants disclosed their previous salary even when prospective employers did not ask were randomized. The applicants were assigned previous salaries between the 75th and 25th percentile of their prior employer’s salary scale for software engineers, as given at Payscale.com in the headquarter cities. A gender wage gap mimicking real-world gaps was built into the applicants by setting female salaries 15 percent lower.

Using an intermediary firm to pose as an employer, the researchers hired 256 US-based recruiters to evaluate the job applications. Each recruiter was given eight applications and a detailed job description. They were asked to recommend whether to call a candidate for an interview, an amount for a take-it-or-leave-it salary offer, and the maximum amount that the firm should be willing to pay the applicant. They also estimated the number of competing offers a candidate would receive and the salary offer each candidate would accept. Recruiters were paid their standard hourly rate and received incentive bonuses.

Recruiters made negative inferences about nondisclosing candidates, especially male nondisclosing candidates. On average, recruiters inferred that candidates who did not disclose had salaries at or slightly below the 25th percentile. Applicants below this level were better off not disclosing their previous pay, in the sense that they received higher offers. The fictional applicants who disclosed received higher mean recommended salaries, $103,993 versus $96,521. Recruiters estimated their mean outside offers to be 9 percent higher than those for nondisclosers.

There are many ways to earn a higher salary; the experiment was designed to measure whether employers notice these distinctions and treat them differently. Some of the candidates came from firms with a high average wage. Some candidates came from lower-wage firms, but were well-paid within their firm’s distribution. Some candidates were simply beneficiaries of the gender wage gap.

Employers in the experiment noticed these distinctions and adjusted their beliefs and choices. An extra $1 of reported salary given to men through the gender wage gap increased recruiters’ estimated value of the applicant to the firm by only $0.42. By comparison, high salaries earned by working at a high-wage firm or being well-paid within an employer’s internal distribution increased recruiters’ value of the worker by $0.64 to $0.70 per $1 of salary. The employers in the experiment detected overpaid men and treated them less generously than others with the same salary. However, they did not completely eliminate the gender wage gap.

The researchers conclude that employers see disclosing salary as a positive signal of candidate quality. However, salary history is also a signal of strong competing offers. A disclosure could increase chances of a callback, but decrease chances of getting a high salary offer, conditional on a callback. Candidates, employers and policymakers may thus face tradeoffs using and regulating salary history information.