The Minimum Wage and Social Security Disability Insurance

The recent policy debate over a possible increase in the federal minimum wage has renewed interest in understanding its effects. While much attention has been paid to possible effects of minimum wage increases on employment, their potential effects on the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program have received far less scrutiny.

SSDI applications increase during times of high unemployment, suggesting that the demand for SSDI is affected by the availability of outside options. If minimum wage increases lead to decreased employment, there may be an increased demand for SSDI benefits among those who are no longer working. On the other hand, as low-wage workers experience an increase in their wage, this lowers the ratio of potential SSDI benefits to potential earnings, which may decrease the demand for SSDI benefits. The effect of a minimum wage increase on SSDI applications and awards is thus difficult to predict without further study.

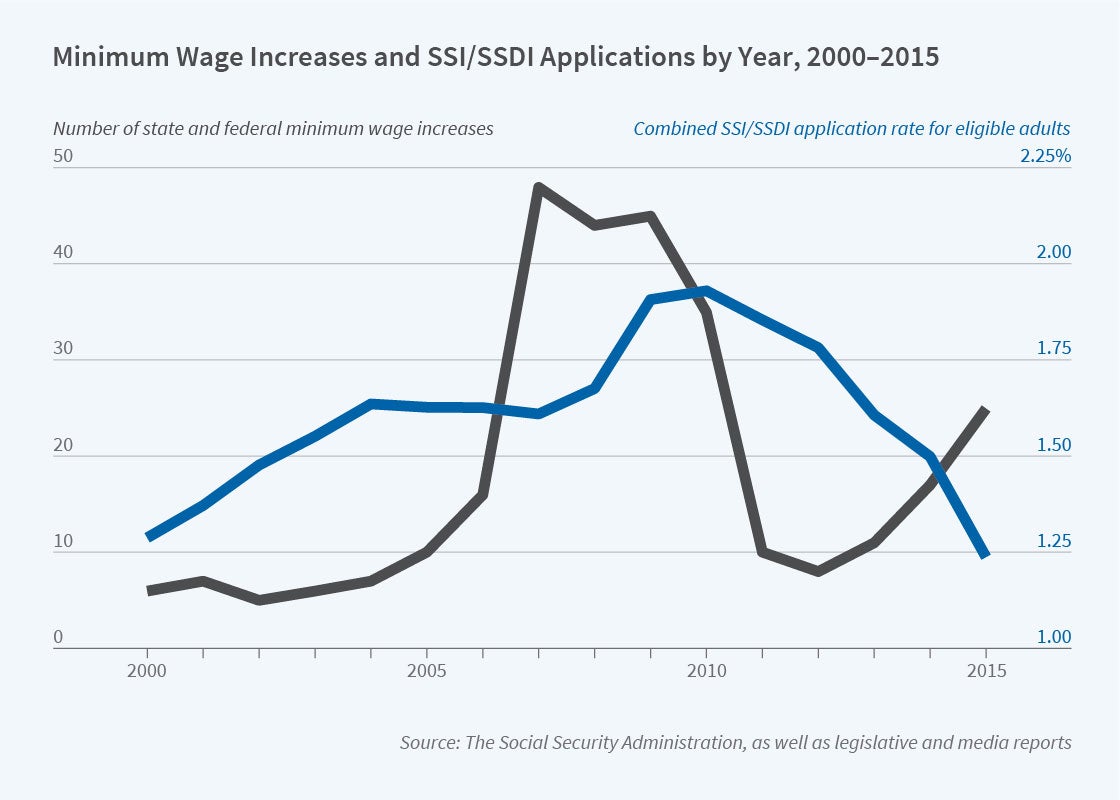

This question is taken up by researchers Mark Duggan and Gopi Shah Goda in their recent study, The Minimum Wage and Social Security Disability Insurance (NBER RDRC Working Paper NB20-17). The authors examine how changes in the minimum wage affected the number of applications to SSDI and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) between 2000 and 2015.

The federal minimum wage was increased three times over the authors’ sample period, from an initial value of $5.15 to $7.25 in 2009. However, many states and local areas set minimum wages above the federal minimum – in 2015, the average in those states setting a higher wage was $8.35. States and localities have raised their minimum wages frequently in recent years – in 2015 alone, 25 states did so. The national combined SSDI and SSI application rate also changed substantially during the sample period, rising from 1.29 percent in 2000 to 1.93 percent in 2010 before declining to 1.24 percent in 2015.

In their analysis, the authors leverage changes in the minimum wage across states over the 2000 to 2015 period. They focus on the state minimum wage, although higher values may be in place in some localities. They control for the unemployment rate and county-level characteristics and include county-level time trends to control for underlying differences across counties in application rates and their growth over time. The data for the analysis is yearly county-level applications for SSDI and SSI from Social Security administrative files.

Turning to the results, the authors find that a one dollar increase in the minimum wage is associated with a 0.04 percentage point increase in the combined SSDI and SSI application rate. This represents a 2 percent increase relative to the sample mean application rate of 1.95 percent. The results are broadly similar across age groups and medical conditions and when looking at SSI and SSDI applications separately. The findings suggest that a one dollar increase in the minimum wage would induce an additional 80,000 SSDI and/or SSI applications.

There is also a robust effect of the unemployment rate on SSDI and SSI applications – a one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate is associated with a 0.04 percentage point increase in the combined application rate. The effect of a one-standard-deviation change in the unemployment rate is about three times as large as the effect of a one-standard-deviation change in the minimum wage.

In concluding, the authors note, “while the county unemployment rate has a strong relationship with the SSDI and SSI application rate, overall our results suggest a small role for the minimum wage in explaining changes in the rate of SSDI and SSI applications. While our effects are economically small, the direction of our point estimates generally are consistent with the minimum wage slightly reducing employment and labor market opportunities, leading a small fraction to apply for disability benefits from SSI or SSDI, on average.”

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant #RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of NBER, SSA or any agency of the Federal Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.