Health Status and Work Capacity Remain High at Older Ages, Especially for Educated Adults

Proposed increases in the eligibility age for retirement benefits raise questions about the health status of older adults and their ability to continue working beyond current retirement ages. In Trends in Work Capacity in the US Population: Are Recent Cohorts in Worse Health? (NBER Working Paper 33733), David M. Cutler, Ellen Meara, and Susan Stewart describe the age profile of health status for older adults in the US, how it has changed across cohorts, and how it differs across socioeconomic groups. They focus on four dimensions of health that contribute to work capacity but have evolved differently: physical functioning, mental health, pain, and cognition.

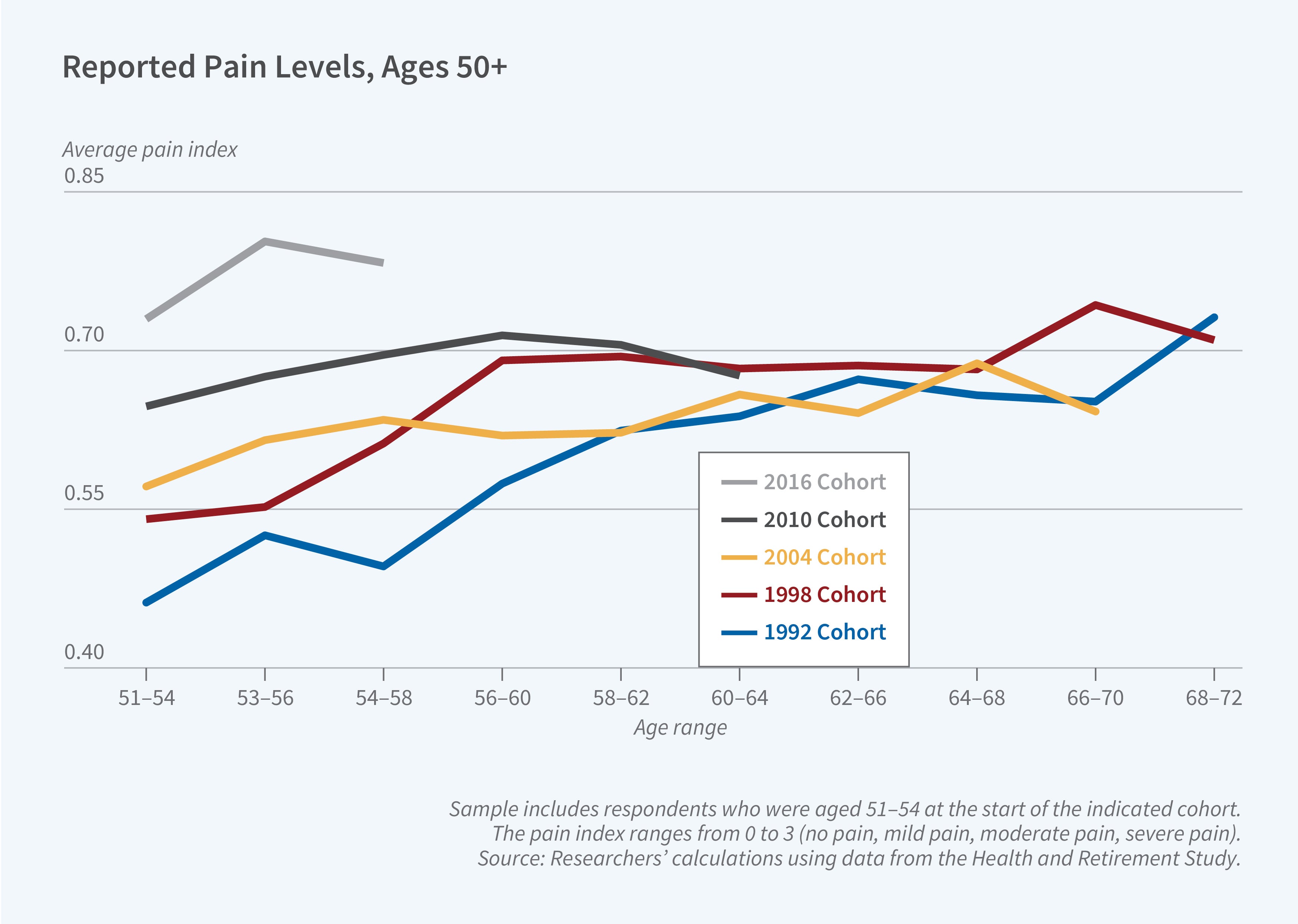

While recent cohorts of older adults have worse pain and cognition in their 50s than earlier cohorts, they also experience slower deterioration of health with age.

Using panel data on older adults from the Health and Retirement Study, the researchers trace each health outcome between ages 51 and 70. Their dataset includes information for five different cohorts of older adults. The earliest cohort was between 51 and 54 in 1992, while the latest cohort reached those ages 24 years later.

Physical functioning, which is measured by self-reported ability to perform activities such as walking one block, is similar across cohorts in their early 50s and does not deteriorate with age as quickly among more recent cohorts. Mental health, which is measured by responses to a depression questionnaire, has been stable, following a similar age pattern across all cohorts.

The onset of pain—which is measured on a 4-point scale from “no pain” to “severe pain”—occurs at younger ages for more recent cohorts. However, pain does not increase with age as much as it did in earlier cohorts; instead, the age profile of pain has flattened. Patterns for cognitive impairment—which is assessed by measures such as immediate and delayed word recall—are similar. As a result, while later cohorts have worse pain and cognition in their 50s than earlier cohorts, the cohorts have similar health status in their 60s.

The researchers use these health measures, and their relationship to employment at ages 51 to 54, to simulate work capacity at ages 62 to 64. Despite the earlier onset of some health limitations for more recent cohorts, the flatter age profile implies that health status, and therefore work capacity, at ages 62 to 64 remains high. In 2020, 62 percent of these older adults had health characteristics that predicted full-time work, 23 percentage points higher than observed rates of full-time employment. This estimate indicates substantial work potential, much of it untapped, among older adults.

However, this work capacity is unevenly distributed across educational groups. More educated adults report better health along each dimension than less educated adults. As a result, 70 percent of college graduates had the capacity to work full-time between the ages of 62 and 64 in 2020, compared to fewer than 45 percent of adults without a high school degree. These findings suggest that any reforms that raise the age of eligibility for retirement benefits would have heterogeneous impacts across socioeconomic groups.

The researchers acknowledge funding from the US Social Security Administration through grant DRC12000002, funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium, from the National Institutes of Health (Award number R37AG047312), and from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.