Why Do More Educated Communities Have Better Health Outcomes?

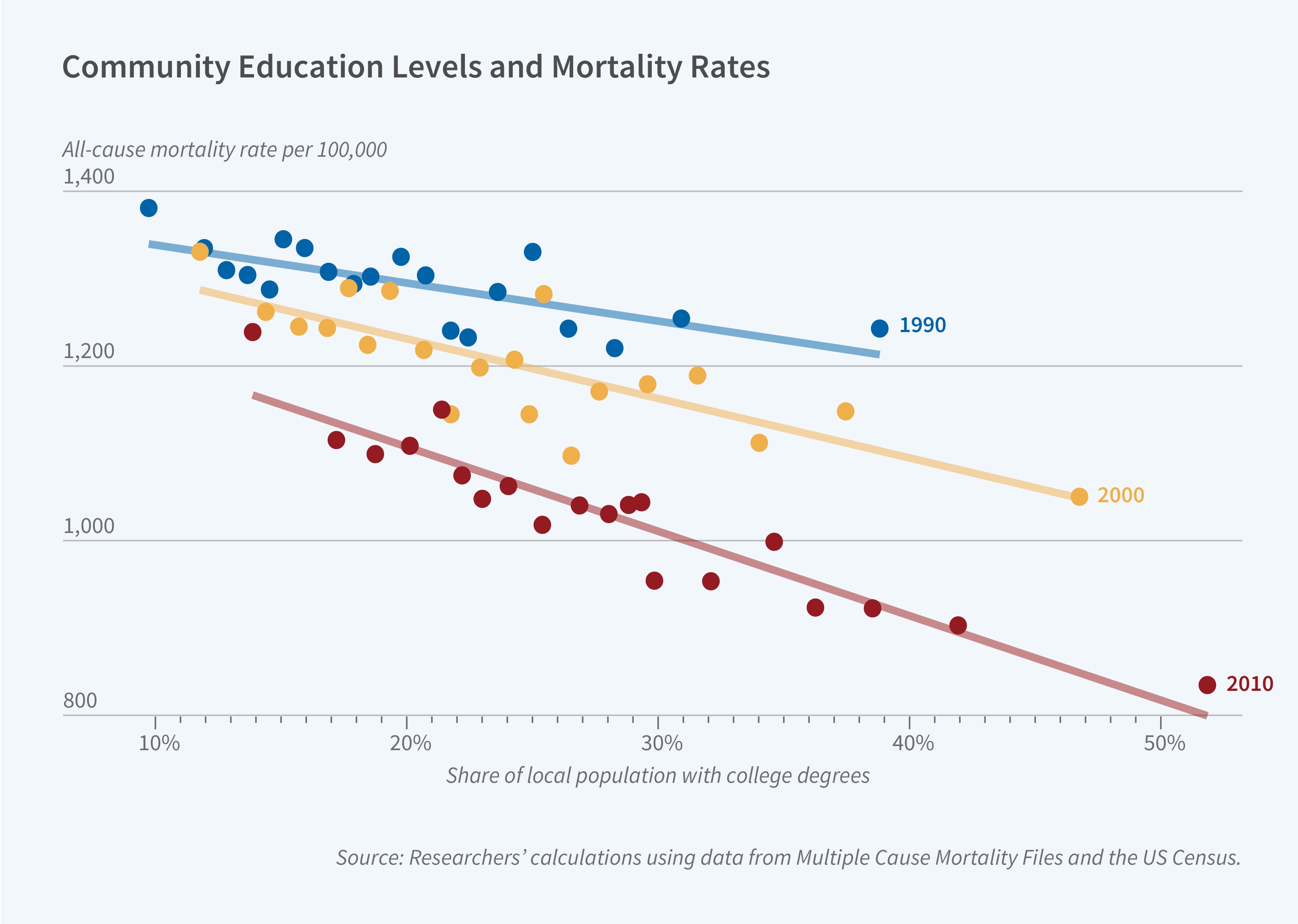

Adults who live in more educated communities have lower mortality rates. In 2010, every 10 percentage point increase in an area’s share of adults with a college degree — equivalent to moving from the 25th to the 75th percentile of area education — was associated with 97 (8 percent) fewer deaths per 100,000 people. In Human Capital Spillovers and Health: Does Living around College Graduates Lengthen Life? (NBER Working Paper 32346), researchers Jacob H. Bor, David M. Cutler, Edward L. Glaeser, and Ljubica Ristovska explore this relationship, examining several mechanisms that might explain it.

Given the well-known correlation between socioeconomic status and health, it may not seem surprising that educational attainment in an area is correlated with its mortality rate. However, even when comparing individuals with equal education, the researchers find that the correlation persists. Only 38 percent of the overall relationship between area education and mortality can be explained by individual educational differences.

The difference in mortality by area education is present for all causes of death, including those that are considered medically amenable, smoking related, obesity related, or attributable to external causes, such as drug overdoses. It is also evident, in survey datasets, for other health outcomes, such as self-reported health status. The overall correlation grew stronger between 1990 and 2010.

The study brings together numerous datasets, including Vital Statistics mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics for all US residents in 1990, 2000, and 2010, and corresponding educational attainment data for each county from the US Decennial Census and the American Community Survey. It focuses on adults over the age of 25.

The researchers first evaluate the hypothesis that this correlation reflects healthier people disproportionately moving to more educated areas. They reject this hypothesis, demonstrating that migration patterns are similar for healthier and sicker people.

Second, they examine differences in health-harming behaviors between areas with more and less educated residents. They focus on two key behavioral risk factors: smoking and obesity. Nearly 60 percent of the correlation between area education and health is explained by differences in smoking and obesity. Adults in more educated areas are less likely to be obese, less likely to begin smoking, and more likely to quit smoking in their 30s or 40s than equally educated adults in less educated areas. The researchers argue that local differences in attitudes, beliefs, social norms, and policies — such as workplace smoking bans — are plausible mechanisms for these patterns.

Finally, they explore the role of local amenities in more educated communities, including less pollution, lower crime rates, and higher-quality medical care. They conclude that these local amenities do mediate the correlation between education and health, but explain no more than 17 percent of the correlation. While they acknowledge that there are many environmental factors that are not measured in their data, they argue that observable environmental factors play a smaller role than behavioral risk factors in explaining this striking correlation.

— Robin McKnight

The researchers acknowledge financial support from the National Institute on Aging and the Taubman Center for State and Local Government.