Higher Prescription Drug Cost-Sharing Raises Mortality among Medicare Beneficiaries

What are the health consequences when patients reduce their use of prescribed medications in response to higher out-of-pocket costs? In The Health Costs of Cost-Sharing (NBER Working Paper 28439), researchers Amitabh Chandra, Evan Flack and Ziad Obermeyer use the distinctive out-of-pocket cost-sharing features of Medicare Part D to demonstrate that such reductions can increase mortality.

Their analysis makes use of the fact that two 65-year-old Medicare enrollees with identical prescriptions, but different birth months, could face radically different out-of-pocket costs at the end of the year. Several unique features of Medicare Part D during the 2007–2012 study period contribute to this fact. The patient’s out-of-pocket share of prescription drug costs (the coinsurance rate) in the standard Part D plan was generally 25 percent when total drug spending was below about $2,500. But the coinsurance rate increased to 100 percent in the “coverage gap” after total drug spending exceeded the $2,500 threshold, before falling to 5 percent above the “catastrophic” spending limit (about $5,700). Beneficiaries tend to enroll in Medicare in the month that they turn 65, but the spending thresholds that determine coinsurance rates are not pro-rated for those who enroll in the middle of the year. As a result of these features, beneficiaries whose birth dates fall earlier in the year are more likely to enter the coverage gap or exceed the catastrophic limit during their first year of coverage.

The researchers use a 20 percent random sample of newly enrolled, 65-year-old Medicare beneficiaries, focusing on December outcomes among those who enrolled between February and September. They report that 11.8 percent of February enrollees fell into the coverage gap in December, while only 1.5 percent of September enrollees did. Similarly, 1.7 percent of February enrollees were in the catastrophic coverage category in December, compared to 0.2 percent of September enrollees.

Of course, beneficiaries with low prescription drug utilization are unlikely to enter the coverage gap, regardless of the timing of their birthday. To better identify the beneficiaries who might enter the different coverage tiers, the researchers use machine learning tools to predict annual prescription drug spending for each Medicare beneficiary. The algorithm predicts what spending would be in the absence of cost-sharing, based on the spending of similar Medicare beneficiaries who face no out-of-pocket costs due to Medicaid eligibility.

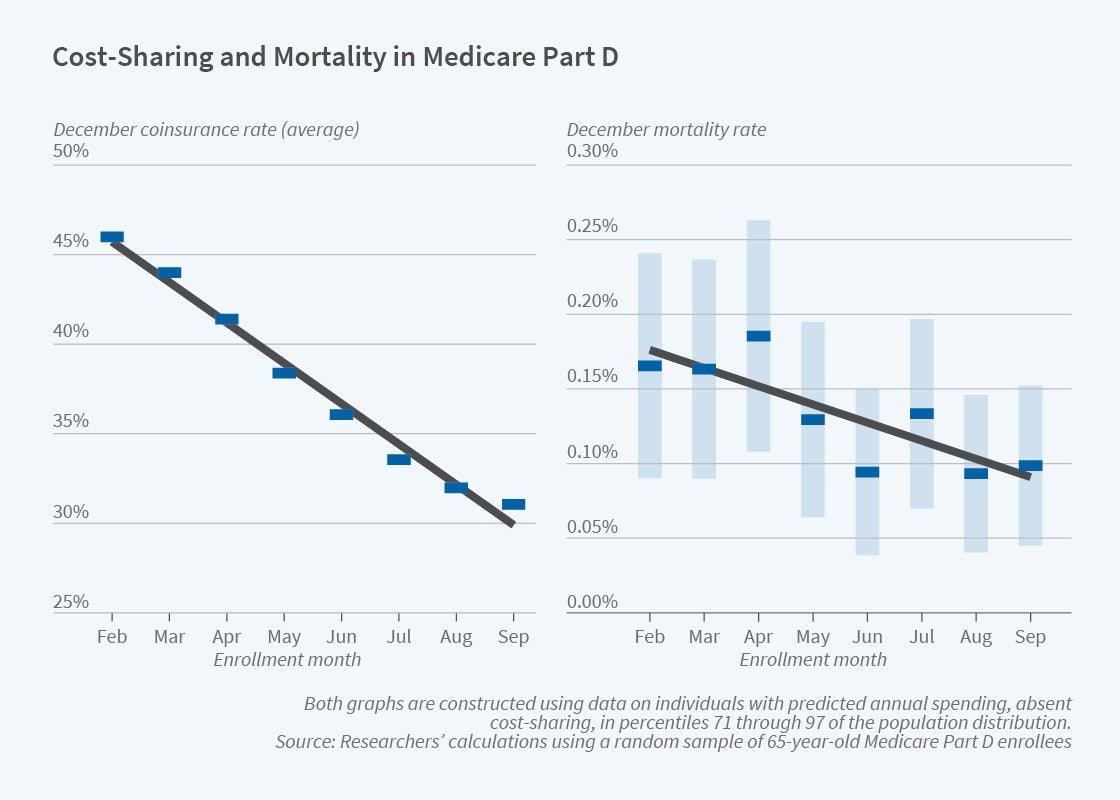

The figure shows outcomes for Medicare recipients with sufficiently high predicted annual prescription costs that they could enter the coverage gap, depending on their birth date, but are unlikely to exceed the catastrophic threshold. Among this group, the first panel shows that December coinsurance rates are highest for those born in February and fall by an average of 2.3 percentage points in each subsequent enrollment month.

The second panel of the figure shows a similar pattern for mortality rates in this group. On average, each month of later enrollment reduces December mortality by 0.0113 percentage points, a 9 percent decrease.

The opposite patterns emerge for beneficiaries with predicted spending in the top 3 percentiles, who could exceed the catastrophic limit and end the year with a 5 percent coinsurance rate. For this group, which is not represented in the figure, each month of later enrollment is associated with a higher December coinsurance rate and a higher mortality rate.

Under the assumption that all of the mortality differences are due to coinsurance differentials, the researchers estimate that a 1 percentage point coinsurance rate increase causes a 0.00435 percentage point increase in the mortality rate. They ascribe these mortality differences to reduced prescription drug utilization induced by the higher out-of-pocket costs. The same 1 percentage point increase in coinsurance is associated with 0.031 fewer filled prescriptions during the month, and a $5.54 reduction in total prescription drug spending across payers. Interestingly, some beneficiaries respond to the increase in out-of-pocket expenses by choosing to fill no prescriptions — regardless of how many drugs they previously took or their individual health risks.

In response to higher out-of-pocket costs, patients cut back on a wide range of medications, including many with mortality benefits that have been established by clinical trials, such as those that control cholesterol, blood pressure and blood sugar. These cutbacks are not limited to patients who are at relatively low risk of adverse health events. On the contrary, the researchers find similar price sensitivity among patients who, based on machine learning predictions, are at greatest risk of adverse events such as heart attacks and strokes.

To rationalize the decisions observed in this study, it would be necessary to assume that the Medicare beneficiaries in the sample valued an additional year of life at $6,628, a value that is at least an order of magnitude below the conventional range of estimates. A plausible alternative explanation is that patients make meaningful errors in evaluating the relative costs and benefits of purchasing prescription drugs.

The standard economic rationale for increased cost-sharing is that it reduces overuse of medical care. But the findings in this study indicate that cost-sharing also results in some ill-considered reductions in treatment that put beneficiary lives at risk. The researchers conclude that redesigning prescription drug insurance to better account for these behavioral patterns would be a cost-effective way to improve health outcomes.

The researchers acknowledge support from grant P01AG005842 from the National Institute on Aging.