Training and Retention of Older Workers in Germany

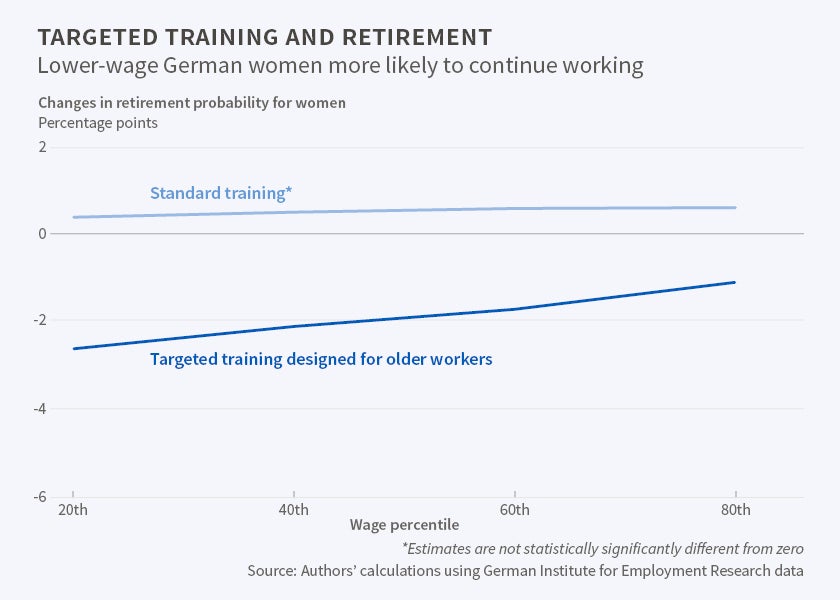

German women over 50, who on average are less financially secure than men, are more likely to improve their pay and delay retirement when employers offer training targeted at older workers.

The combination of declining birth rates and increasing longevity in developed countries means labor forces are aging and in some nations shrinking. These patterns are particularly evident in Germany, where the population is expected to decline by 18.8 percent over the next 15 years. The labor force will age and may contract by as much as 35 percent. German firms have responded to these demo-graphic changes by instituting targeted training programs intended to induce workers to stay on the job beyond traditional retirement age.

In The Relationship between Establishment Training and the Retention of Older Workers: Evidence from Germany (NBER Working Paper 21746), Peter B. Berg, Mary K. Hamman, Matthew M. Piszczek, and Christopher J. Ruhm discover that when employers offer training programs targeted at older workers, women —especially low-wage women — are more likely than men to continue working beyond traditional retirement age.

The researchers, who analyze data from the Linked Employer-Employee Dataset of Germany's Institute for Employment Research, cannot definitely explain this gender disparity. They suspect, however, that lifetime earning patterns play a key role. Men nearing traditional retirement age tend to have longer histories of uninterrupted employment than women and higher lifetime earnings, as well as higher average wages. They may be near the top of relevant pay scales, so the promise of slightly higher wages for additional years of employment may be less attractive to them than the promise of substantially higher wages for such years to women.

Because many women interrupted their working careers to raise families, their potential wage gains associated with targeted retraining are often much larger than the gains for men. Because of their often-interrupted work histories, women tend to qualify for smaller pensions than men, and, more generally, women are far more likely to be financially insecure. For many women, training programs focus on getting them up to speed regarding developments on the job that occurred while they were out of the labor force. The study strongly suggests that offering targeted training may both improve women’s earnings and encourage longer working lives.

—Matt Nesvisky