Assessing Federal Subsidies for Purchases of Electric Vehicles

A modified program that raise the tax incentive for low-income vehicle buyers and lowered it for high-income buyers could have induced the same increase in overall EV purchases at a smaller revenue cost.

Federal tax incentives, which totaled $725 million in 2014, are generally credited for the rapid increase in sales of electric vehicles (EVs) in the past decade. Because EVs offer a locally cleaner alternative to cars that run on gasoline, the U.S. government encourages EV purchases by offering tax credits ranging from $2,500 to $7,500.

Did these subsidies induce consumers to ditch their gas-guzzlers, or would consumers who obtained the tax benefits have bought EVs anyway? In What Does an Electric Vehicle Replace? (NBER Working Paper 25771), Jianwei Xing, Benjamin Leard, and Shanjun Li find that federal tax credits induce EV sales, but that the majority of the credits went to households that would have purchased an EV without any tax incentive.

Mass-market EVs became available in late 2010 at a premium relative to other fuel-efficient cars. For example, in 2014 the Honda Accord Hybrid cost about $30,000, but the electric plug-in Honda Accord cost over $40,000.

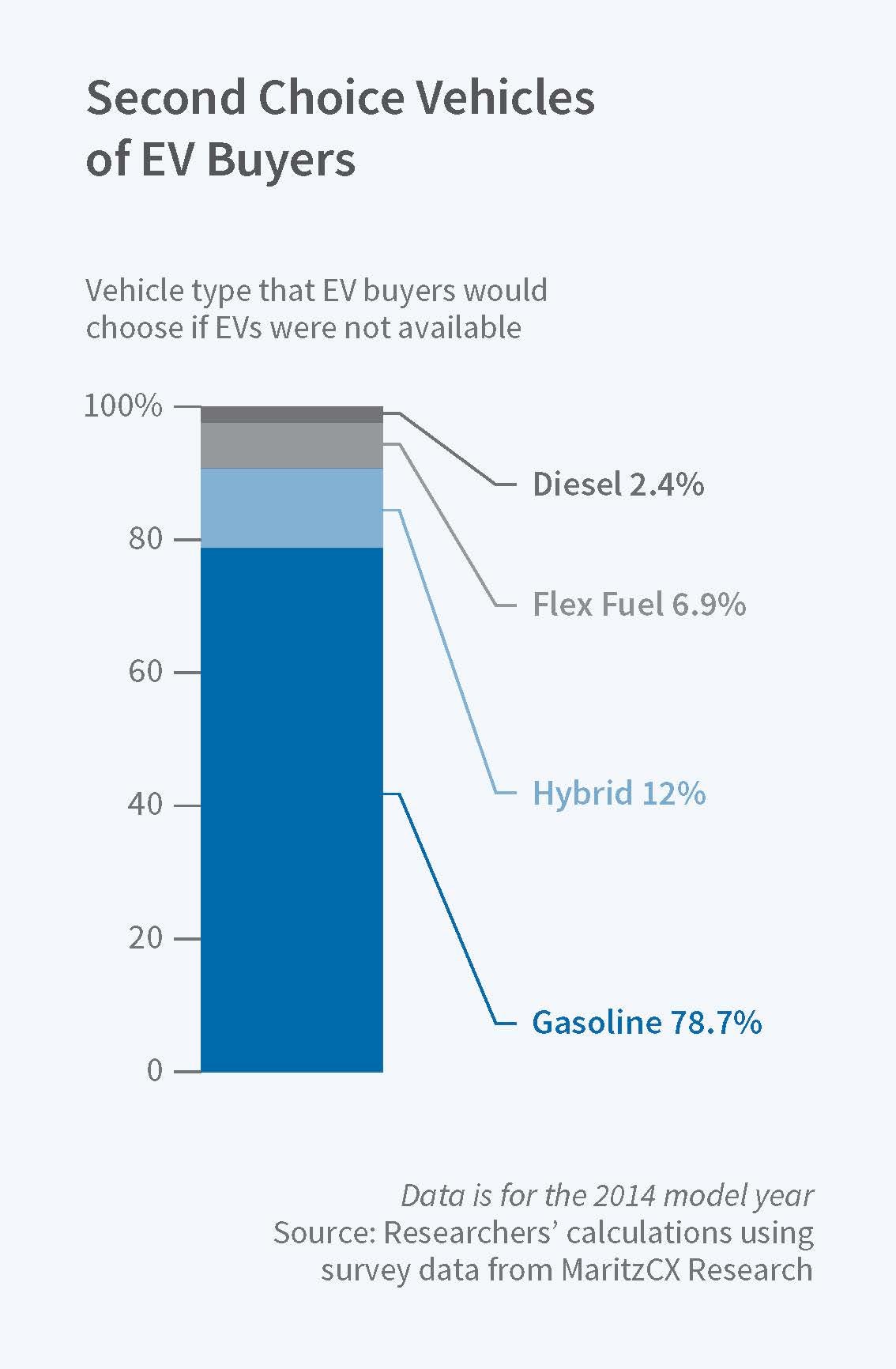

To assess the economic and environmental benefits of EV adoption, the researchers estimate what vehicles households would have purchased in place of EVs. To do this, they analyze 2010-14 household survey data, which include information on households' car purchases as well as the other vehicles that the household considered buying, to create a counterfactual scenario without EV tax incentives.

The researchers estimate that without tax subsidies, EV purchases would have fallen by about 29 percent. They find that "EVs mainly attracted consumers who were originally choosing mid-size and fuel-efficient gasoline or hybrid vehicles, rather than gas-guzzlers such as large SUVs or trucks." High-income households were more likely to reap the benefits of the tax subsidy but were also more likely to buy EVs in the absence of an incentive, relative to lower-income households. The researchers calculate that a modified program that provided a larger tax incentive for low-income vehicle buyers, who are more price-sensitive than their high-income counterparts, could have induced the same increase in overall EV purchase at a smaller revenue cost.

While electric vehicle purchases have grown over the last decade, sales of conventional hybrid vehicles have plateaued. The researchers find that this occurred not because EVs replaced hybrids, but rather because the federal government stopped offering tax incentives for hybrids.

The study estimates that the tax subsidy for EVs is responsible for about 30 percent of the CO2 emissions reduction from the current EV fleet in the U.S. These calculations assume that EVs replace the cars that households would have bought otherwise, not the "average" car on the U.S. highway. Because EV buyers on average are more environmentally conscious than the overall car-buying population, the emissions reduction is smaller — by about 27 percent — than it would be if EVs replaced average U.S. vehicles.

— Morgan Foy