Eliminating Earnings Test Increases Ranks of Low-Income Older Women

The change encouraged some workers to claim Social Security benefits earlier than they otherwise would have, decreasing their benefits.

Until 2000, the Retirement Earnings Test (RET) reduced the net Social Security benefits of some senior citizens who had income from working. Then the test was eliminated for seniors who have reached full retirement age in an effort to encourage those who want to work to continue doing so. The change allows seniors working past retirement age to avoid reduction in their Social Security benefits. But it also encourages them to claim Social Security benefits earlier than they otherwise would, which lowers their annual benefit payments.

At older ages, after individuals no longer have income from labor, this reduction in benefits may translate into lower financial status, especially for women, who tend to live longer, according to the analysis in Does Eliminating the Earnings Test Increase the Incidence of Low Income Among Older Women? (NBER Working Paper 21601).

"The results for the sample first observed at age 70 or older suggest that, as women age into their mid-70s, the effect of lower Social Security benefits from early claiming comes to dominate the effects of higher earnings (and whatever effect those higher earnings had on income from saving)," researchers Theodore Figinski and David Neumark report.

Using Health and Retirement Study data, the authors compare two samples: nearly 3,000 women ages 70 and 71 and nearly 2,000 women ages 75 and 76. The study concentrates on older women because they are more likely than men to have become principally dependent on their Social Security benefits. The authors confirm what previous research has shown: Congress's elimination of the RET in 2000 caused women to claim Social Security benefits months earlier than they otherwise would have. By one estimate, women who were 69 in 2000 claimed about 6.5 to 7.8 months earlier. Rates are even higher for slightly younger women, who could take greater advantage of the changes in the law. Those who were 65 or younger in 2000 claimed 8.2 to 9.6 months earlier. The result: lower annual benefits of about $650 to $800, according to the researchers' estimates.

A similar result is found for the husbands of married women: their husbands also tend to claim benefits earlier, leading to lower annual benefits for the couple of about $1,500.

For a time, the extra income that the early claimants earn from work tends to offset the lower benefits associated with early claiming. Previous research suggests that elimination of the RET through age 69 boosted seniors' earnings by 19 to 20 percent. But that advantage dissipated in later years as earnings declined and seniors continued to receive lower annual Social Security payments because they elected to begin receiving their benefits at an earlier age.

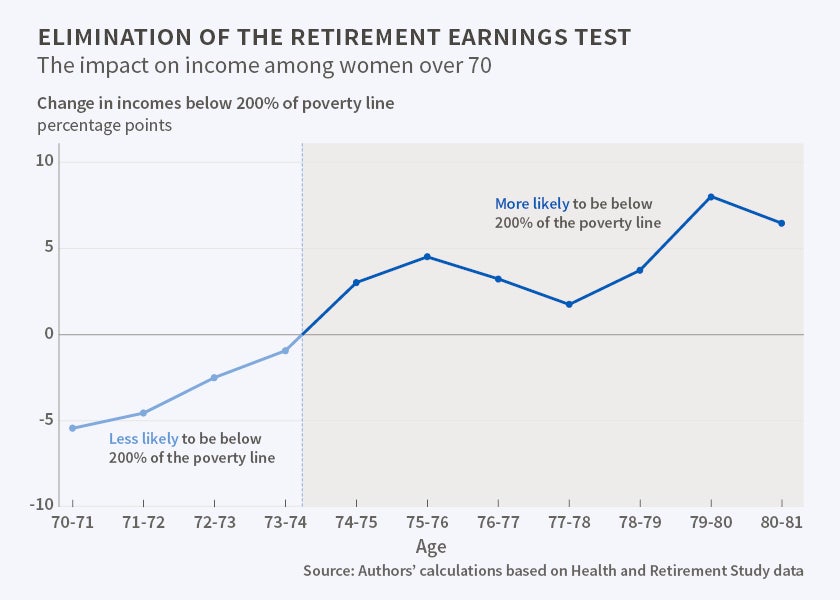

The authors find that women affected by the elimination of the RET who are 70 or older are 5.5 percentage points less likely to be below 200 percent of the poverty line than those not affected by the elimination of the RET. The older these women get, the greater their risk of having income that is below, or close to, the poverty line. Women 75 or older are 3.4 to 4.5 percentage points more likely to fall under the 200 percent poverty line. For older women whose husbands are observed, the net effect is similar but more muted; they are 2.9 to 3.8 percentage points more likely to be under the 200 percent poverty line.

"The results for poverty and low-income status tend to fit the conjecture about higher income and hence of lower incidence of low income initially – when women are at or just above age 70 – but a higher incidence of low income as women get into their mid-70s and beyond," the researchers conclude. "These findings suggest that the incidence of low income among old women was increased by the elimination of the RET."

—Laurent Belsie