Technological Advance and Labor Demand: Evidence from Two Centuries

There have been concerns about technological progress displacing workers since the start of the Industrial Revolution, but systematic evidence on how such advances affect labor demand is limited. In Technology and Labor Markets: Past, Present, and Future; Evidence from Two Centuries of Innovation (NBER Working Paper 34386), Huben Liu, Dimitris Papanikolaou, Lawrence D. W. Schmidt, and Bryan Seegmiller construct novel measures of exposure to technological change for occupations between 1850 and 2020 by applying natural language processing and large language models to patent documents.

They first use large language models to generate comprehensive task descriptions for each US Census occupation in each decade and then measure exposure by calculating the semantic similarity between patent summaries and these task descriptions. Motivated by a simple model in which workers optimally choose how to allocate their time across tasks, while technology can substitute for certain tasks, the researchers measure both the average technology exposure across an occupation's tasks as well as the degree to which this exposure is concentrated in a few tasks.

The researchers then study the relationship between employment by occupation, as reported in decennial censuses, and their technology exposure measures. They find that occupations with 1 standard deviation higher mean technological exposure experienced 11–13 percentage points lower employment growth over the next decade. Consistent with their theoretical framework, however, when technology exposure is concentrated in specific tasks, labor demand increases: A 1standard deviation increase in exposure concentration leads to about 6–7 percentage points higher employment growth, holding mean exposure constant.

Examining industry-level effects using data from 1910 onward, the researchers find that increases in industry-relevant patents were associated with about 8–11 percentage points higher employment growth over 10 years, capturing productivity spillover effects.

Between 1910 and 2020, employment growth was about 3.1 percentage points higher per year for the most highly educated relative to the least-educated occupation groups. Total occupational exposure to technological progress explained about 35 percent of this gap. In the full sample, the researchers' measures of technological exposure account for roughly half of the observed 1.7 percentage points per year shift toward low-skill service occupations and away from middle-skill jobs, and about 43 percent of the 2.1 percentage points per year relative shift towards high-skill occupations. They also account for nearly half of the 1.6 percentage points per year relative growth in female-intensive occupations.

Technology-induced employment reallocation fell heavily on incumbent workers relative to labor market entrants. Older cohorts experienced significantly larger negative employment effects from mean exposure, consistent with older workers having accumulated specialized skills tied to older technologies that became less valuable when innovations arrived.

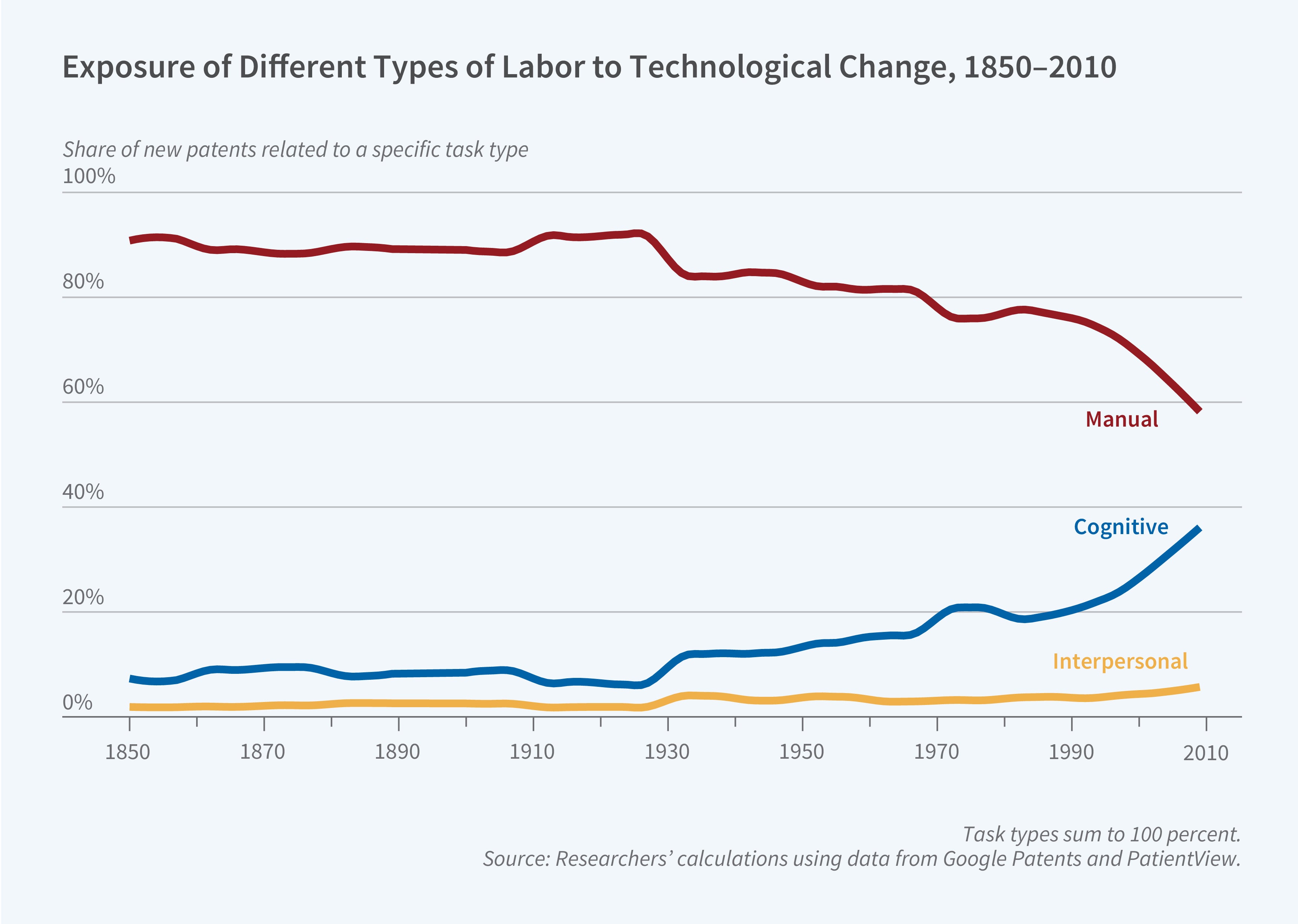

Examining heterogeneity by task type also uncovered a secular shift in technological exposure towards cognitive tasks. Manual task exposure predicted employment declines throughout the sample. Cognitive task exposure showed time-varying effects: Before 1960, it was associated with employment gains, but in later years, its effect was negative. During this same time period, cognitive tasks were becoming more exposed to technology relative to manual tasks. The researchers conclude that the Information and Communication Technologies revolution fundamentally changed how technology interacted with cognitive work.

The researchers use their empirical findings to inform a model-simulation-based forecast of how AI might affect labor markets. Assuming that AI primarily substitutes for cognitive tasks requiring less than five years of specific vocational preparation, the baseline forecast predicts an increase in relative demand for middle-skill occupations of between 0.29 and 0.85 percentage points per year relative to different types of white-collar work, with the largest gain being relative to technicians and clerical workers. There is also an increase in male-dominated occupations of 0.53 percentage points per year. This suggests that while twentieth- century technological change consistently favored more educated, higher-paid, and female-intensive occupations, AI may substantially alter these long-standing patterns by automating cognitive rather than manual tasks.

Dimitris Papanikolaou and Bryan Seegmiller thank the Financial Institutions and Markets Research Center and the Asset Management Practicum at Kellogg-Northwestern for their generous financial support.