Movie Subtitles and English Language Acquisition

Most discussions of foreign-language acquisition, particularly English, focus on classroom instruction. But schools are not the only source of English-language skill development. Western entertainment media, primarily movies and TV shows, are disproportionately produced in English. Consuming these products provides another avenue for developing English skills, especially considering that in many developed countries, time spent watching TV is equivalent to time spent in school. In Out-of-School Learning: Subtitling vs. Dubbing and the Acquisition of Foreign-Language Skills (NBER Working Paper 33984), Frauke Baumeister, Eric A. Hanushek, and Ludger Woessmann estimate the effect of subtitling versus dubbing on English-language acquisition from cross-country differences. They find a large positive effect of subtitling on skill development.

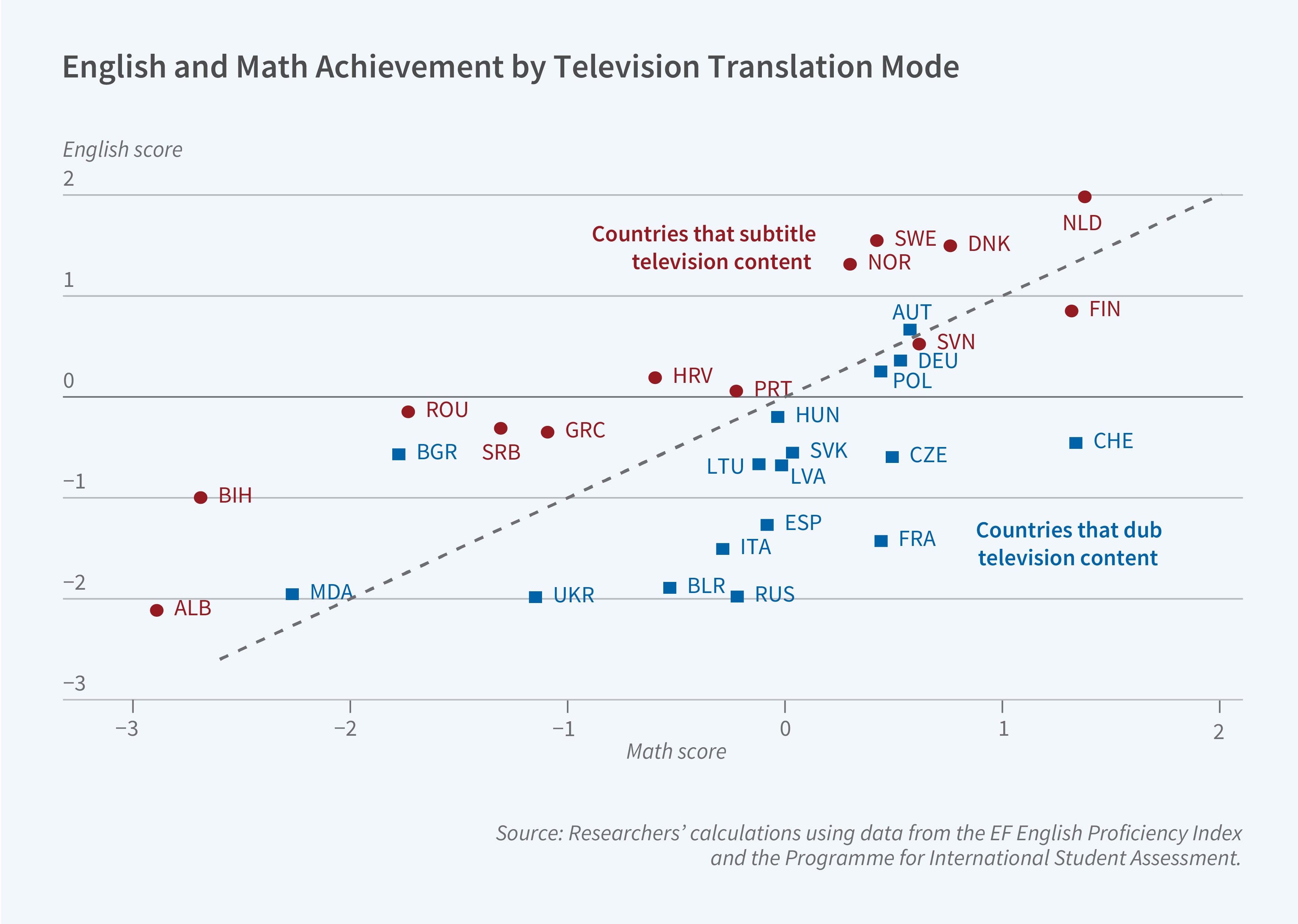

Countries that use subtitling rather than dubbing for foreign TV content demonstrate significantly higher English proficiency.

Countries’ choices of whether to subtitle or dub are historical, generally made soon after sound films emerged in the 1920s. Subtitling exposes viewers to the English voice track, while dubbing does not. The sample is evenly divided between countries where subtitling is common, such as the Nordic countries and the Netherlands, and those where dubbing is common. The latter group includes France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

Under the assumption that math skills are not affected by TV translation mode, cross-country differences provide a measuring stick against which to benchmark whether subtitling affects language skills. To test the impact of subtitling on language outcomes, the authors use three different measures of English proficiency: the EF English Proficiency Index (EF EPI), the world’s largest ranking of countries by adult English skills; the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), a standardized test that is widely used for college applications; and the Adult Education Survey (AES), which draws on representative samples, but proficiency is self-rated rather than test-elicited. The counterfactual math achievement score comes from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), a standardized test of representative samples of 15-year-olds.

There is a strong positive effect of subtitling on the population’s English proficiency. The effects exceed 1 standard deviation in most specifications. The baseline estimate of the subtitling effect on EF EPI scores is 1.4 standard deviations. Average estimates for the representative AES are similar, which suggests that the results are not driven by selective test taking. In the AES, the effect of subtitling is about 1.5 standard deviations in the youngest group (aged 16–34) but also exceeds 1.2 standard deviations for those between ages 35–44. For the TOEFL test, the effects are smaller on average but consistent. The effect on TOEFL scores differs by domain, reaching 1.2 standard deviations in speaking but not reading—in line with oral learning from subtitled TV.

These estimates are best interpreted as long-run effects that capture not only impacts of individual TV viewing but also intergenerational effects running through improved English skills of parents and teachers. This analysis shows the powerful impact of non-school factors on learning.

— Lauri Scherer

This work was supported by the Smith Richardson Foundation. The contribution of Woessmann is also part of German Science Foundation project CRC TRR 190.