The Changing Distribution of the Return to Higher Education

Higher education has played a central role in reducing income inequality and the intergenerational persistence of socioeconomic status in the US during the twentieth century. However, the average return to attending college for students from families in different strata of the income distribution is not the same and has diverged in recent decades. Students from higher-income families receive greater wage benefits from college attendance than their lower-income peers.

In Changes in the College Mobility Pipeline Since 1900 (NBER Working Paper 33797), Zachary Bleemer and Sarah Quincy report that the average wage premium associated with college attendance by lower-income Americans has halved, relative to that for students from higher-income families, since 1960. The researchers analyze dozens of longitudinal surveys and administrative datasets spanning more than a century to measure wage premiums, defined as the difference in early-30s earnings between those who completed at least one year of college and high school graduates who did not attend college.

Since 1960, the wage premium from attending college for students from high- and low-income families has diverged.

In the first half of the twentieth century, students from the bottom and top thirds of the parental income distribution received similar average wage premiums from college attendance. However, a divergence emerged beginning around 1960. By the end of the twentieth century, the college wage premium for students from the top income tercile was twice as large as that for bottom-tercile students. Between 1950 and 2000, the college-going premium for top-tercile students rose by about 0.14 log points relative to bottom-tercile students.

Three factors appear to explain about 80 percent of this growing disparity. First, the teaching-oriented public universities where lower-income students concentrate have experienced relative declines in quality indicators like funding, retention rates, and economic value since 1960. The gap in annual per-student revenue between institutions attended by lower- and higher-income students grew by $67 per year between the 1960s and the 1990s, then accelerated to $100 per year through the 2010s.

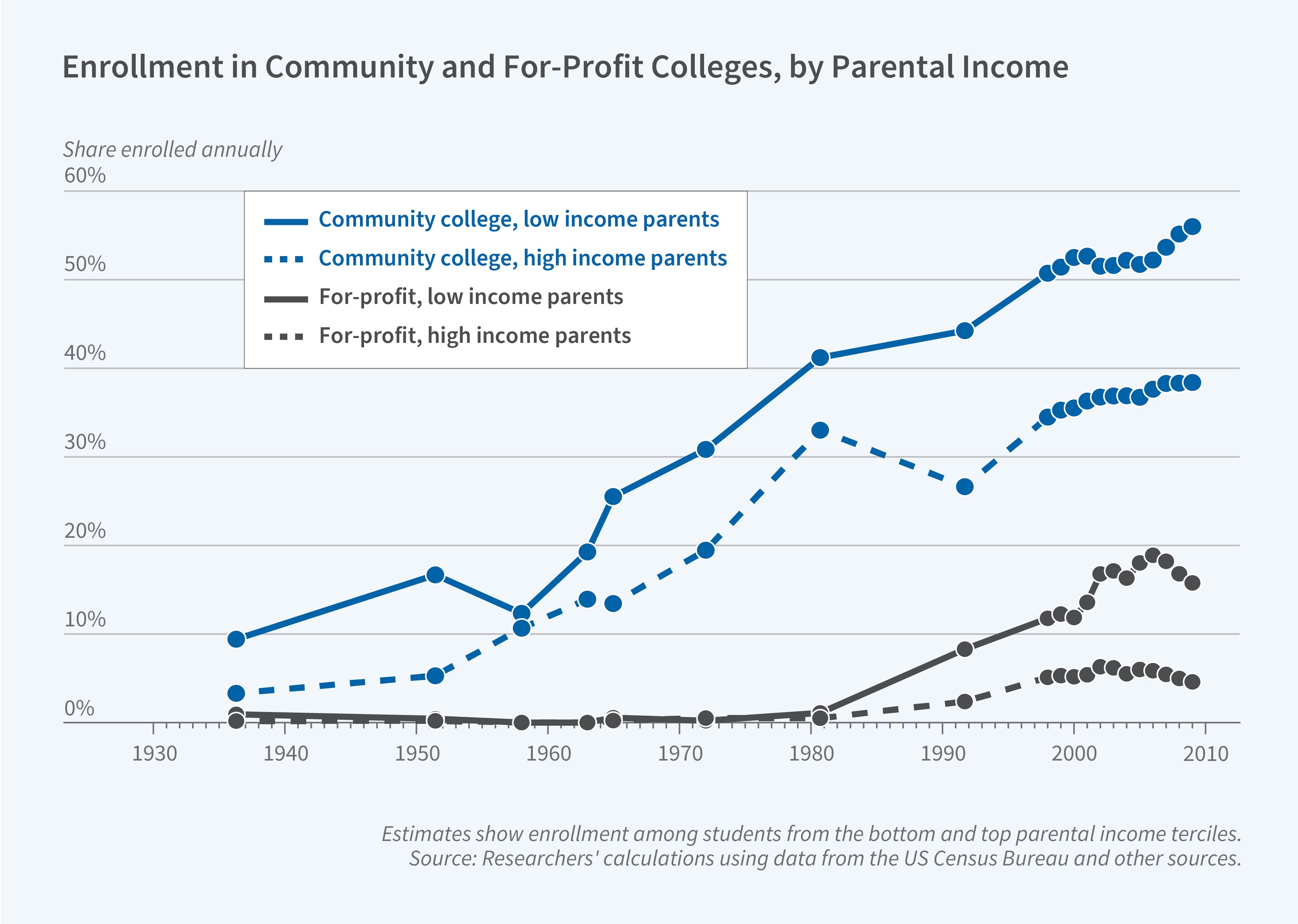

Second, lower-income students who attend college have increasingly attended community colleges (since about 1980) and for-profit institutions (since about 1990). The gap in two-year college enrollment between bottom- and top-tercile students was less than 10 percentage points before and through the 1970s, but it exceeded 20 percentage points after 1990. For-profit enrollment among bottom-tercile students rose from near zero to 20 percent between 1980 and the early 2000s before regulatory changes reduced the size of this sector.

Third, shifts in college major choices since 2000 have widened the earnings gap. Higher-income students have increasingly moved out of humanities fields and into computer science and economics/finance programs, while lower-income students have not. About 40 percent of the recent increase in major stratification across income groups is due to higher-income students' increased declaration of computer science majors while nearly 20 percent is due to lower-income students' growing concentration in lower-value humanities fields.

The researchers also explore several other potential explanations of the growing disparity in returns to college, including differential selection into college based on pre-college cognitive skills, changes in enrollment patterns across four-year universities resulting from rising selectivity or tuition, and shifts in the relative value of different majors over time, and conclude that they are at most modest contributors.

Disparities in the return to college attendance today can account for as much as 25 percent of the transmission of income from one generation to the next, up from virtually no effect in 1960.