How and Why Black Riders Were Driven from American Racetracks

Between 1890 and 1899, African American jockeys won the Kentucky Derby six times. By the early 1900s, they were history.

In Jim Crow in the Saddle: The Expulsion of African American Jockeys from American Racing (NBER Working Paper 28167), Michael Leeds and Hugh Rockoff document the expulsion of African American jockeys from the Triple Crown races as a striking example of the surge in racism in the 1890s. The researchers suggest that horse racing provides a particularly helpful case study for untangling Jim Crow’s effects because it was popular both in the North and the South, was integrated for years after the Civil War, and offers quantitative data that reflect underlying attitudes. Using a new dataset that includes information on all entrants in all races, they find some evidence of prejudice by horse owners and the betting public, but conclude that the final push for expulsion came from White jockeys who were determined to “draw the color line.”

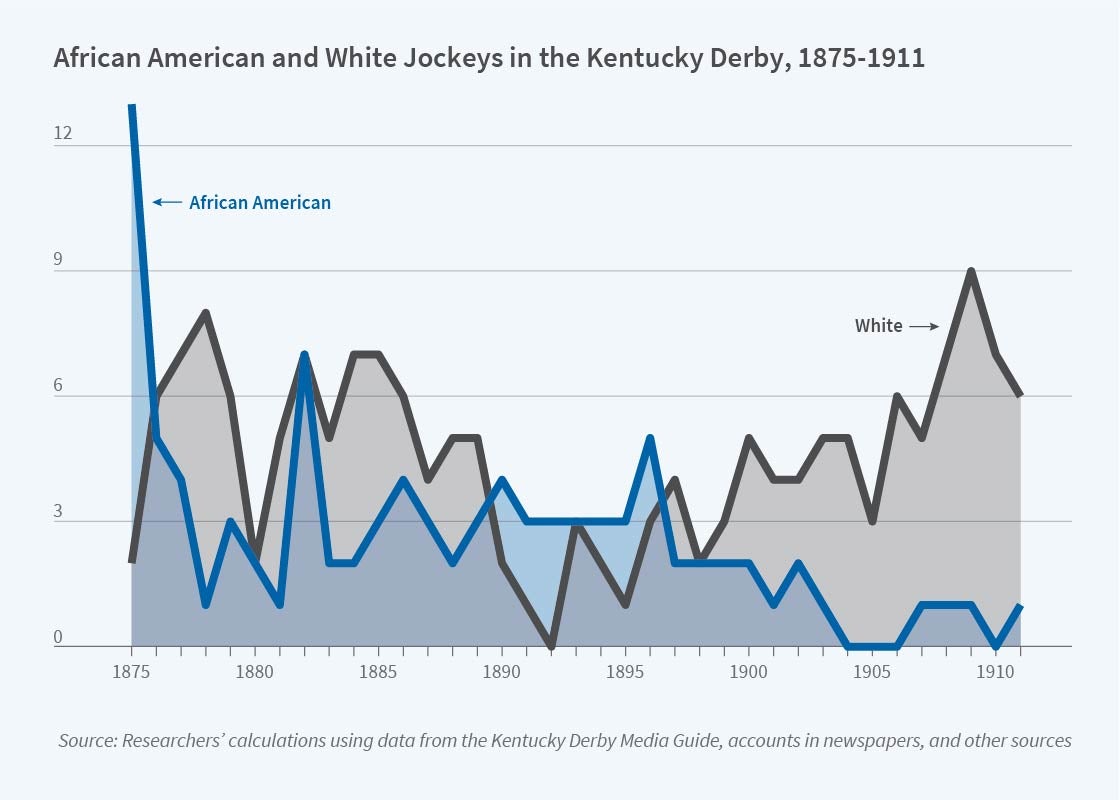

In the years following the Civil War, as in the pre-war era, most jockeys on Southern tracks were African American. At the first Kentucky Derby, in 1875, 13 of 15 jockeys were African American. Between 1890 and 1899, Black jockeys won six Derbies, one Preakness Stakes, and three Belmont Stakes. But in the early 1900s Black jockeys disappeared. Jimmy Winkfield was the last African American to win a Triple Crown race, in 1902. He was one of the last African Americans to ride in a Triple Crown race for almost a century.

The researchers test for the presence of discrimination against Black jockeys in two ways. First, they study the relationship between the rise of Jim Crow and the decline in the number of mounts going to Black riders. Second, they examine whether a particular class of jockeys outperform the odds, which reflect the bets that race spectators have placed. This test could detect spectator discrimination against Black jockeys.

The researchers do not find any evidence of racial prejudice by the betting public for races run on Northern Triple Crown tracks, but they find some evidence of such prejudice at the Kentucky Derby. Horses ridden by Black jockeys were more likely to finish in the money (first, second, or third) than predicted by the odds. This suggests that bettor preferences at the Derby may have contributed to the expulsion of African American jockeys.

The key push to exclude Black jockeys came when White jockeys began violently attacking their African American counterparts by boxing them out during races, running them into the rail, and hitting them with riding crops. These attacks prevented Black jockeys from finishing in the money, and endangered fragile and valuable racehorses. Soon after the attacks began, African American jockeys found they could not get rides. Anxiety over job insecurity appears to have played an important role in White jockeys’ actions: there were only a limited number of riding slots. White jockeys would have benefitted in any circumstances from the exclusion of Black jockeys, but in the late 1890s the US was in a depression, and unease about finding rides was especially high. Combined with a growing anti-gambling crusade that reduced attendance at racetracks and eliminated some tracks entirely, jockeys found demand for their services contracting.

Owners tacitly participated in the expulsion of African American jockeys. For some, it could have been a matter of prejudice, but for others, it was likely a business decision. Why employ a Black jockey if White jockeys would use violence to prevent him from finishing in the money, and risk damaging a valuable horse in the process?

The researchers conclude that African American jockeys were victims of discrimination at multiple levels. The findings add to the evidence that anxiety about jobs was an important contributing factor to the racism that produced Jim Crow.

— Lauri Scherer