Does the Timing of Disability Benefit Payments Affect Labor Supply?

Individuals with a disabling health condition often experience lower income and higher medical expenses in the wake of disability onset, leading to reduced consumption and well-being. If these individuals are cash-constrained, the value of benefits may be particularly high at the beginning of benefit receipt. In this case, receiving a lump sum could improve beneficiary outcomes more than receiving smaller monthly payments.

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefits are paid as monthly cash benefits but awards also include an initial lump sum payment including benefits back to the date of entitlement – five months after disability onset – if the award is made after this date. There is little research exploring the structure and timing of disability benefit payments in SSDI or other disability programs.

Researchers Kathleen Mullen and Stephanie Rennane begin to address this gap in their recent study Understanding the Impact of Cash on Hand on the Labor Supply of Disabled Workers (NBER RDRC Working Paper NB19-Q3).

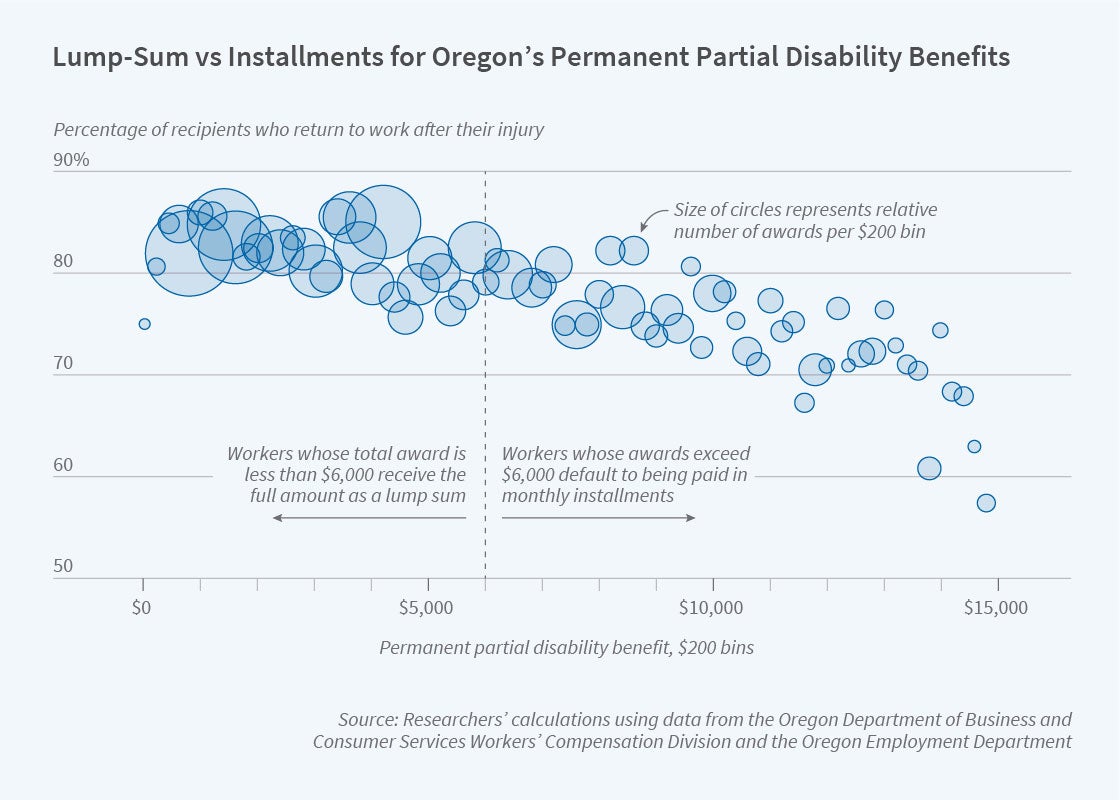

The authors take advantage of a change in the default payment method of permanent partial disability (PPD) awards in the workers’ compensation program in Oregon. Workers whose total PPD award is less than $6,000 receive the full amount of their benefit as a lump sum, while those whose awards exceed $6,000 default to be paid in monthly installments. The authors use this change in payment method to examine whether the receipt of benefits as a lump sum affects the labor supply of disabled workers. PPD benefits are paid regardless of subsequent work activity, so any effect would be a response to the change in income rather than to any change in the incentive to work.

The authors obtain administrative data from Oregon covering all workers’ compensation claims from 2001 to 2009 matched to earnings information from the state’s unemployment insurance records. The empirical approach involves looking for evidence of a change in behavior at the $6,000 threshold at which the default payment method switches from lump sum to monthly benefits. The authors show that workers just above and below this threshold have similar characteristics and that workers cannot manipulate the award amount, suggesting that any change in behavior at the threshold can be attributed to the effect of the change in default payment method.

The authors find no evidence of a change in labor supply at the $6,000 threshold. This result holds whether looking at the decision to return to work, earnings, or hours in the first quarter after the closure of the claim. The $6,000 threshold is even more salient for low-wage workers, whose monthly benefits would be smaller and spread out over more months – however, there is no evidence of labor supply effects at the threshold for this group.

The authors conclude, “overall, these results suggest that default assignment to a lump sum payment or monthly installment around this particular benefit threshold amount of $6,000 does not have a significant effect on labor supply decisions for workers with permanent partial disabilities resulting from on-the-job injuries in Oregon.” They suggest that the difference between receiving $6,000 at once or approximately $1,000 to $2,000 per month over three to five months may not constitute a large enough change in cash on hand to affect labor supply. Recipients may be anticipating the end of the cash benefit and making return-to-work decisions based on a longer time horizon. The authors suggest that future work could “explore whether larger differences in the level and duration of monthly vs. lump sum payments have meaningful effects on outcomes of workers with disabilities.”

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant #RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of NBER, SSA or any agency of the Federal Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.