What Accounts for the Rise in Suicide Rates in the US?

Annual suicide deaths per 100,000 people in the US increased gradually from 10 in 1950 to 13 in 1970 then experienced a long decline, reaching a trough at 10 in 2000. Between 2000 and 2020, however, the US suicide rate exhibited an upward trend.

Two aspects of this increase are especially notable. The first is its speed. Between 2000 and 2020, the suicide rate rose from 10 per 100,000 to just over 14 — a 40 percent increase in only 20 years, and enough to temporarily catapult suicide into the top 10 causes of death in the US. The second was the absence of other countries experiencing similar trends. Out of a comparison group of 16 OECD countries, 12 experienced decreases in suicide rates between 2000 and 2020, and of the remaining four countries, the US experienced by far the largest increase.

In The Re-Emerging Suicide Crisis in the US: Patterns, Causes, and Solutions (NBER Working Paper 31242), Dave Marcotte and Benjamin Hansen investigate recent trends in US suicide rates and attempt to understand the factors underlying them.

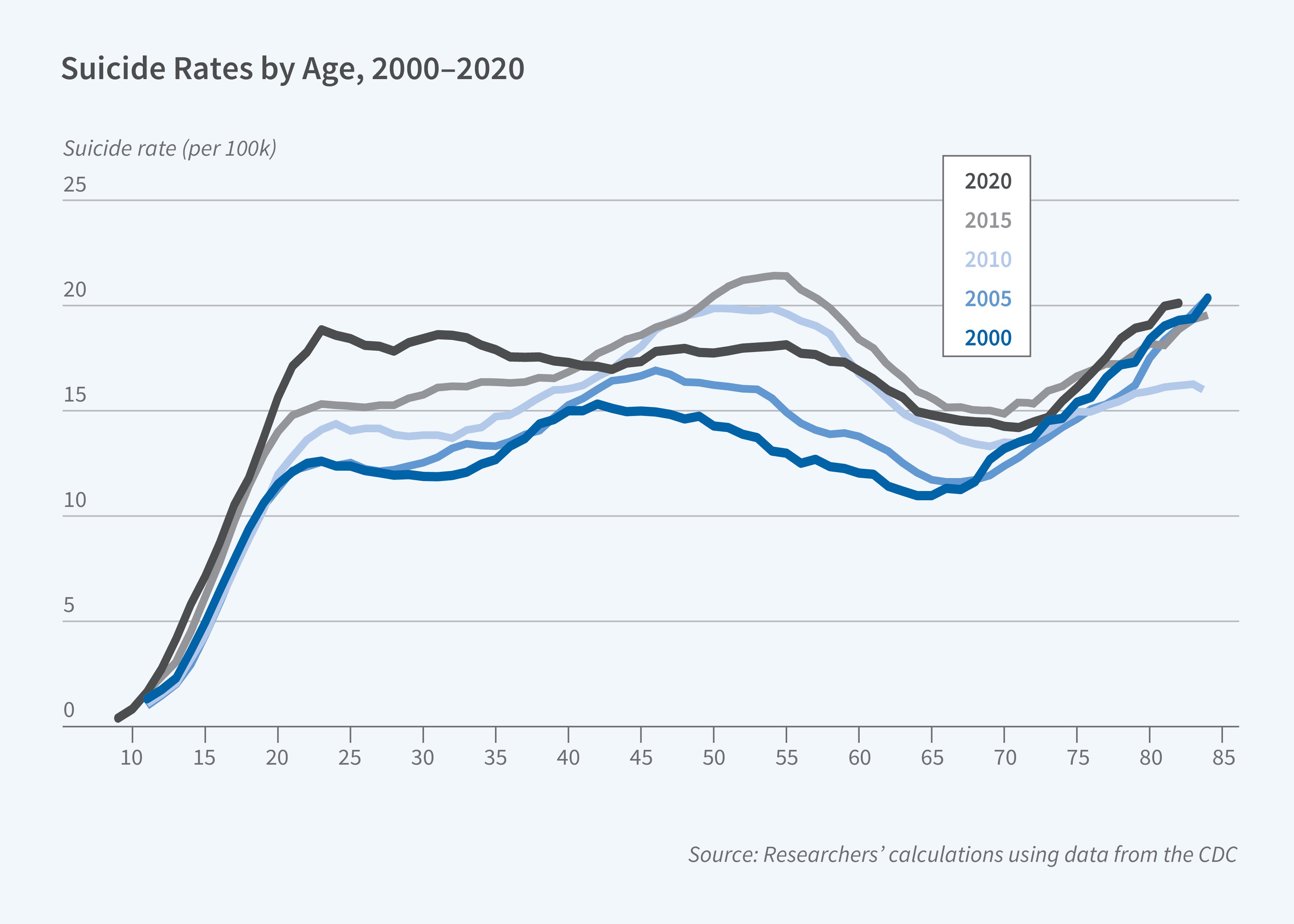

Rising suicide rates in the US since 2000 were driven by an increase in the rates for middle-aged and older adults in the 2000s and by rising rates for younger people in the 2010s.

The researchers begin by studying suicide rates by age group. The increase in aggregate suicide rates between 2000 and 2020 can be decomposed into two episodes: a large increase in suicides among middle-aged and older adults in the 2000s, and then a large increase among teens and young people in the 2010s.

The researchers point to the Great Recession as a potential contributing factor to the increase in middle-aged suicides. While suicide rates in this age group rose somewhat between 2000 and 2005, they accelerated after 2005. The suicide rate for 55-year-olds rose from 15 to 19.6 per 100,000 in just five years between 2005 and 2010, coinciding with the arrival of the Great Recession in 2007. Middle-aged suicides continued to climb until 2015, perhaps reflecting persistent economic malaise following the recession.

Meanwhile, the rise in youth suicide after 2010 was accompanied by a rapid increase in depression among adolescents and young adults. Nearly all of the increase in suicide mortality can be explained by the increase in the prevalence of depression during the 2010s among those aged 25 and younger. One often-cited explanation, a rise in bullying, does not seem to have been a major factor. While being a victim or perpetrator of bullying has a well-documented effect on suicide, particularly among LGBTQ victims, studies have shown stability or a decline in bullying rates over this same time period. Bullying, however, is an important factor underlying the base level of youth suicide rates. The increase in the proportion of youth identifying as LGBTQ also likely explained a small portion of the suicide increase, even with relatively stable bullying rates of this group. The increase in youth suicide did coincide with large increases in rates of social media usage and smartphone ownership, and the researchers cite both observational and quasi-experimental studies showing negative correlations between adolescent social media usage and mental health.

Several other factors are commonly invoked as potential drivers of US suicide rates. Opioid-related deaths also rose dramatically between 2000 and 2020, driven by the proliferation of synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and accidental deaths from opioid overdoses can be hard to distinguish from suicides. However, the researchers point out that opioid-related deaths and the availability of fentanyl exploded only after 2013, later than the acceleration of suicide deaths.

Gun availability is also sometimes cited as a driver of American suicide rates; the US is unique worldwide in having guns as the most common method of suicide. The number of gun sales in the US increased between 2000 and 2020, but the share of households owning a gun declined. Moreover, between 2000 and 2020, non-gun suicides increased faster than gun suicides. The researchers conclude that while guns may be an important factor underlying the base level of US suicide rates, they are unlikely to explain the recent increase. They note the exception of suicides among children in their early teens, where access to unsafely stored household guns might be a particularly important driver of suicide.

The researchers conclude that the key drivers of recent changes in suicide rates are factors that affect motive, including declining mental health and well-being, especially among youth, and economic hardship among the middle-aged. These are factors that might be affected by expansions of mental health coverage, antibullying programs, and policies that provide income and housing security.

—Shakked Noy