Urgent Care Centers Raise Medicare Costs

Urgent care centers (UCCs) have proliferated in recent years: the share of zip codes served by a UCC rose from 28 percent in 2006 to 91 percent in 2019. The implications of this market expansion for overall health care costs are not obvious. If UCCs divert patients from costly emergency departments (EDs), then UCC access could reduce costs. But, if UCCs initiate demand for additional services, they could raise costs. Researchers Janet Currie, Anastasia Karpova, and Dan Zeltzer address the question of how the entry of UCCs into a market affects health care costs for Medicare beneficiaries in Do Urgent Care Centers Reduce Medicare Spending? (NBER Working Paper 29047).

Using a 20 percent random sample of elderly, fee-for-service Medicare enrollees between 2006 and 2016, the researchers compare the changes in health care spending in communities where UCCs entered to changes in communities where UCCs had not yet entered. Not surprisingly, this comparison indicates that UCC utilization trends upward after a UCC enters the market. UCC spending rises from about $0 per beneficiary before entry to $6 per beneficiary six years later.

The analysis shows that UCC entry does not affect the prevalence of the types of ED visits that could plausibly be displaced by UCC visits: those that do not result in a hospitalization. Likewise, UCC visits do not appear to substitute for physician office visits or outpatient care, as UCC entry has no impact on use of these services.

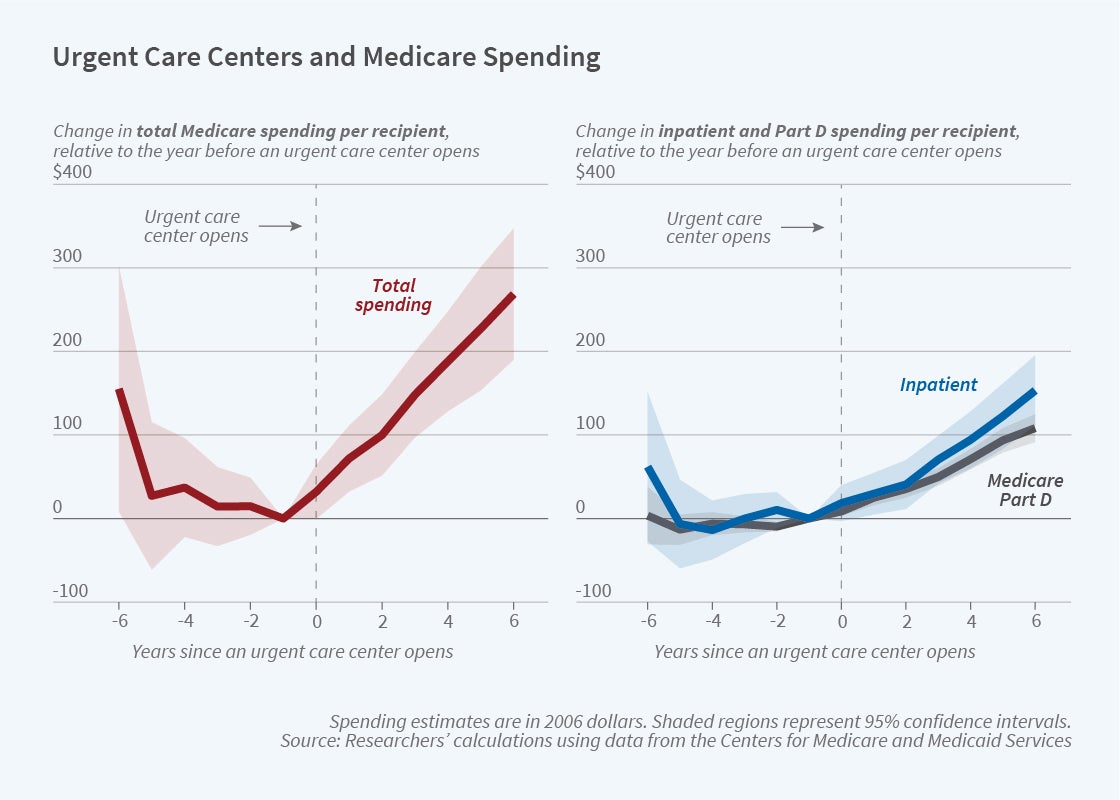

Instead, the researchers find that UCC entry increases Medicare costs by much more than the average per-beneficiary UCC costs. The first panel of the figure shows that total Medicare spending per enrollee begins trending upward when a UCC enters a community. By the sixth year after entry, the increase in annual Medicare spending is $269 per beneficiary (a 2 percent increase relative to the average spending level in 2006). Mortality rates, meanwhile, remain unchanged when UCCs enter a market, raising the question of what the additional Medicare spending buys.

As the second panel of the figure shows, the incremental spending is concentrated in inpatient and prescription drug spending. By the sixth year after entry, these costs have risen by $153 per beneficiary (4 percent) and $108 per beneficiary (10 percent), respectively. The change in inpatient costs is attributable to an increase in hospital stays, especially elective admissions, while the increase in prescription drug spending is due to a shift in the composition of prescribed medications towards higher-priced drugs.

Overall, the findings do not support the hypothesis that UCCs displace costly ED visits. Instead, they are consistent with concerns that UCCs may induce additional demand for hospital care.

The researchers acknowledge support from the National Institute on Aging grant numbers P01AG005842 and P30AG012810 and from the Israel Science Foundation grant number 1461/20.