The Value of Medicaid

Medicaid is the largest means-tested program in the U.S., with expenditures of over $425 billion in 2011. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, a recent expansion of the Medicaid program in that state that occurred by random assignment, has provided some of the most compelling evidence to date on the program's effects. A series of previous studies analyzing this experiment has found that Medicaid coverage: increases health care use; improves self-reported health and mental health while having no effect on mortality or physical health; reduces the risk of large out-of-pocket medical expenditures; and has no significant effect on employment, earnings, or private health insurance coverage (for more details, see http://www.nber.org/oregon/).

Despite this recent work, however, it has not been clear how to assess the value of the Medicaid program. How do the welfare benefits of the program compare to its costs? How do the program's benefits compare to the benefits of other cash-based transfer programs?

These questions are taken up by researchers Amy Finkelstein, Nathaniel Hendren, and Erzo F. P. Luttmer in their recent paper The Value of Medicaid: Interpreting Results from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment (NBER Working Paper 21308).

In the absence of a detailed framework to estimate the value of Medicaid, the program's worth has generally been assessed using an ad hoc approach. The Congressional Budget Office, for example, values Medicaid at the average government expenditure per recipient. The program's true value to recipients, however, could be either more than its cost (if individuals face difficulties buying private insurance due to market failures) or less than its cost (if administrative costs or excess use of care due to moral hazard lessen the program's worth, or if Medicaid crowds out other forms of insurance, such as uncompensated care).

In their study, the authors develop two analytical frameworks for estimating the value of Medicaid empirically. The "complete-information" approach requires the authors to specify all elements that affect an individual's well-being and the causal effect of Medicaid on each of these elements. The "optimization" approach focuses on the ways in which Medicaid affects the individual's budget set and assumes that individuals make optimal choices with regard to their budget set. Appealingly, these two approaches are essentially opposite in the type of assumptions that the authors must make in order to implement them. By comparing the results of these two alternative frameworks, the authors are less reliant on any particular assumption.

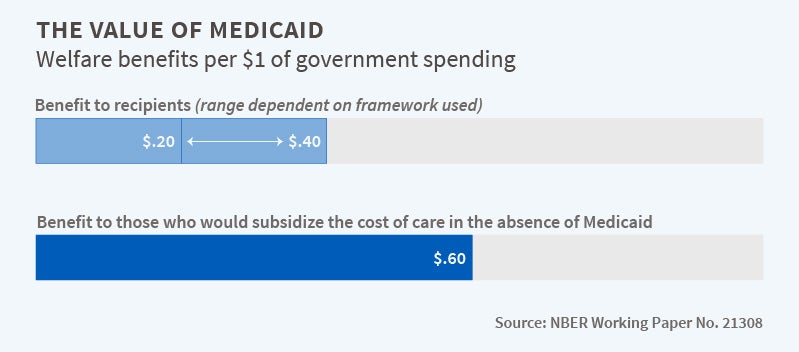

The authors begin with the question of whether Medicaid recipients would be willing to cover the government's cost of Medicaid. Their answer is a fairly robust "no." Their baseline estimates indicate that the welfare benefits to recipients per dollar of government spending are between $0.20 and $0.40, depending on the framework used. Using a variety of alternative assumptions widens the range of possible valuations from $0.15 to $0.85. All of these estimates are less than the full valuation approach used by the Congressional Budget Office.

A key reason for the finding that recipients value Medicaid at less than the full cost of the program is that the uninsured pay only a small fraction of their medical expenditures. Put differently, if there was no Medicaid, this population would still receive some health care and would pay only a small share of its cost, likely due to the large amount of uncompensated care provided by hospitals. The authors estimate that about $0.60 of every dollar of government Medicaid spending represents a transfer to external parties who subsidize the cost of care in the absence of Medicaid.

An alternative question is whether Medicaid is a preferable form of redistribution to low-income individuals relative to the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which also benefits this group. If a "benevolent social planner" needed to reduce either Medicaid or EITC expenditures by a given dollar amount, which would be the preferred option?

Here, the authors' answer is "it depends." If the planner values $1 in the hands of a Medicaid recipient less than $0.90 to $3.00 in the hands of an EITC recipient, then the planner should cut Medicaid. Of course, the Medicaid population is arguably more economically disadvantaged than the EITC population and may also be in worse health, which could lead the planner to place more value on transfers to this group and rationalize a willingness to make more costly transfers. The wide range depends largely on the assumptions of who ultimately bears the cost of uncompensated care, highlighting the importance of future work in this direction.

The authors conclude, "our paper illustrates the possibilities — but also the challenges — in doing welfare analysis even with a rich set of causal program effects. Behavioral responses are not prices and do not reveal willingness to pay without additional assumptions. We provide a range of potential pathways to welfare estimates under various assumptions, and offer a range of estimates that analysts can consider, rather than the common defaults of zero valuation or valuation at government cost."

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Institute of Aging under grants RC2AG036631 and R01AG0345151 (Finkelstein) and the NBER Health and Aging Fellowship, under the National Institute of Aging grant T32-AG000186 (Hendren).