Student Borrowing: Debt, Default, and Repayment

Three significant economic trends in the United States and other developed countries have altered the landscape of higher education substantially in recent decades, with important implications for student borrowing and repayment behavior, Alex Monge-Naranjo and I argue in a series of recent papers.1 First, the costs of college have increased markedly, even after accounting for inflation and expansions in student aid. Second, average returns to college (net of tuition payments) have increased sharply. Third, labor market uncertainty has increased considerably, highlighted by the Great Recession.

The first two trends, rising costs and returns to college, have contributed to a dramatic increase in demand for student loans. Annual student borrowing levels doubled in the 1990s and then again over the next decade.2 Combined government and private student debt levels in the U.S. quadrupled from $250 billion in 2003 to $1.1 trillion in 2013, reflecting sizeable increases in both the incidence of debt and debt levels among borrowers.3

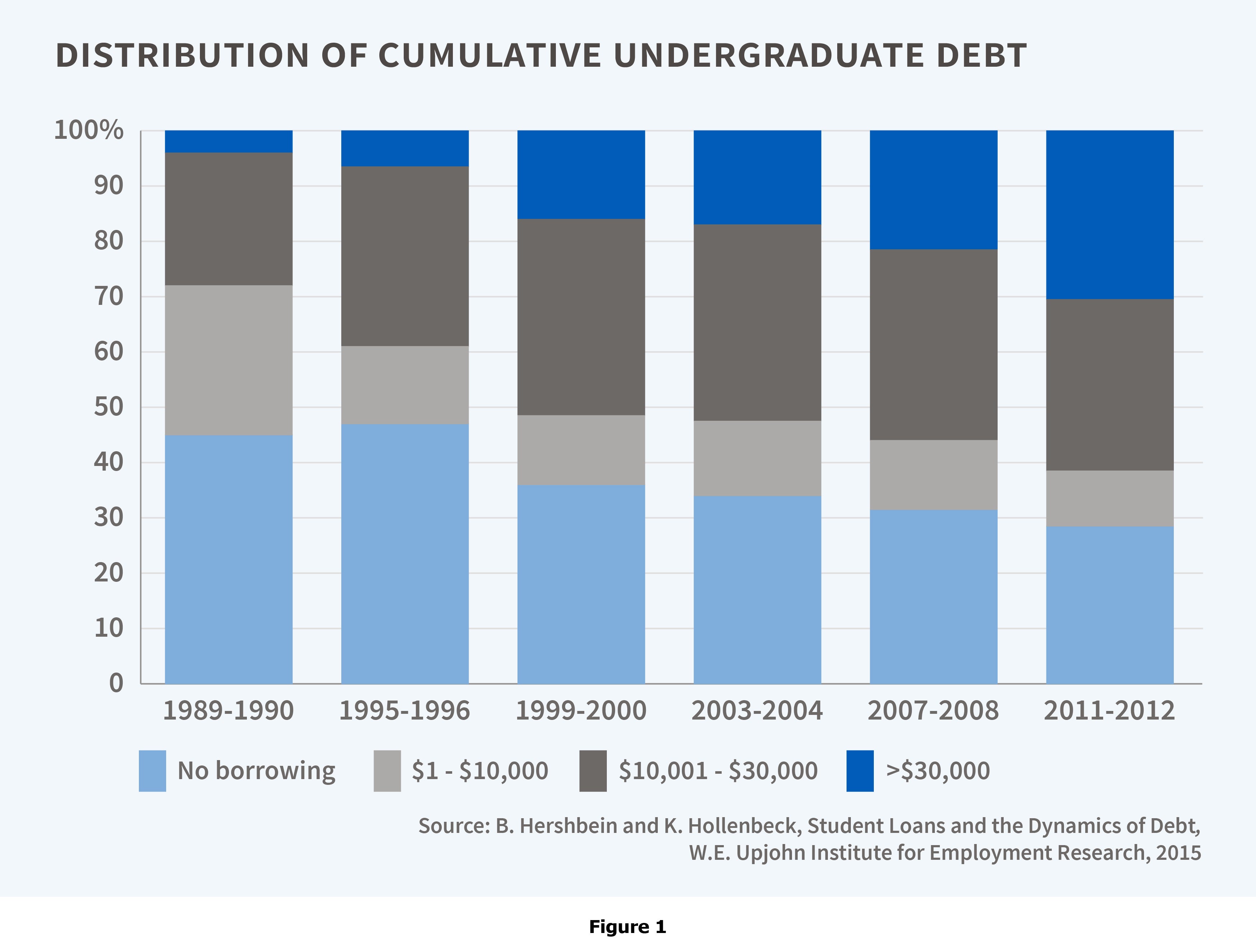

Figure 1 documents the changing distribution of cumulative debt among U.S. baccalaureate recipients since 1989-90. The fraction of college graduates borrowing less than $10,000, including non-borrowers, declined from over 70 percent to less than 40 percent, while the fraction of college graduates borrowing more than $30,000 rose from 4 percent to 30 percent.4

The steady rise in student borrowing over the late 1990s and 2000s masks the fact that government student loan limits remained unchanged (in nominal dollars) between 1993 and 2008. Adjusting for inflation, this reflects a nearly 50 percent decline in value. In 2008, aggregate Stafford loan limits for dependent undergraduate students jumped from $23,000 to $31,000, although this value was still less than the 1993 limit after accounting for inflation. Not surprisingly, the share of full-time/full-year undergraduates that maxed out Stafford loans increased more than five-fold from 1989-90 to 2003-04.5 Undergraduates turned more and more to private lenders to help finance their education prior to the 2008 increase in federal student loan limits and contemporaneous collapse in private credit markets.

Undergraduate borrowing from non-federal sources peaked at 25 percent of all undergraduate borrowing. Despite this increase in private lending, there are reasons for concern that a growing fraction of youth from low-income and even middle-income backgrounds are unable to access the resources they need to attend college.6

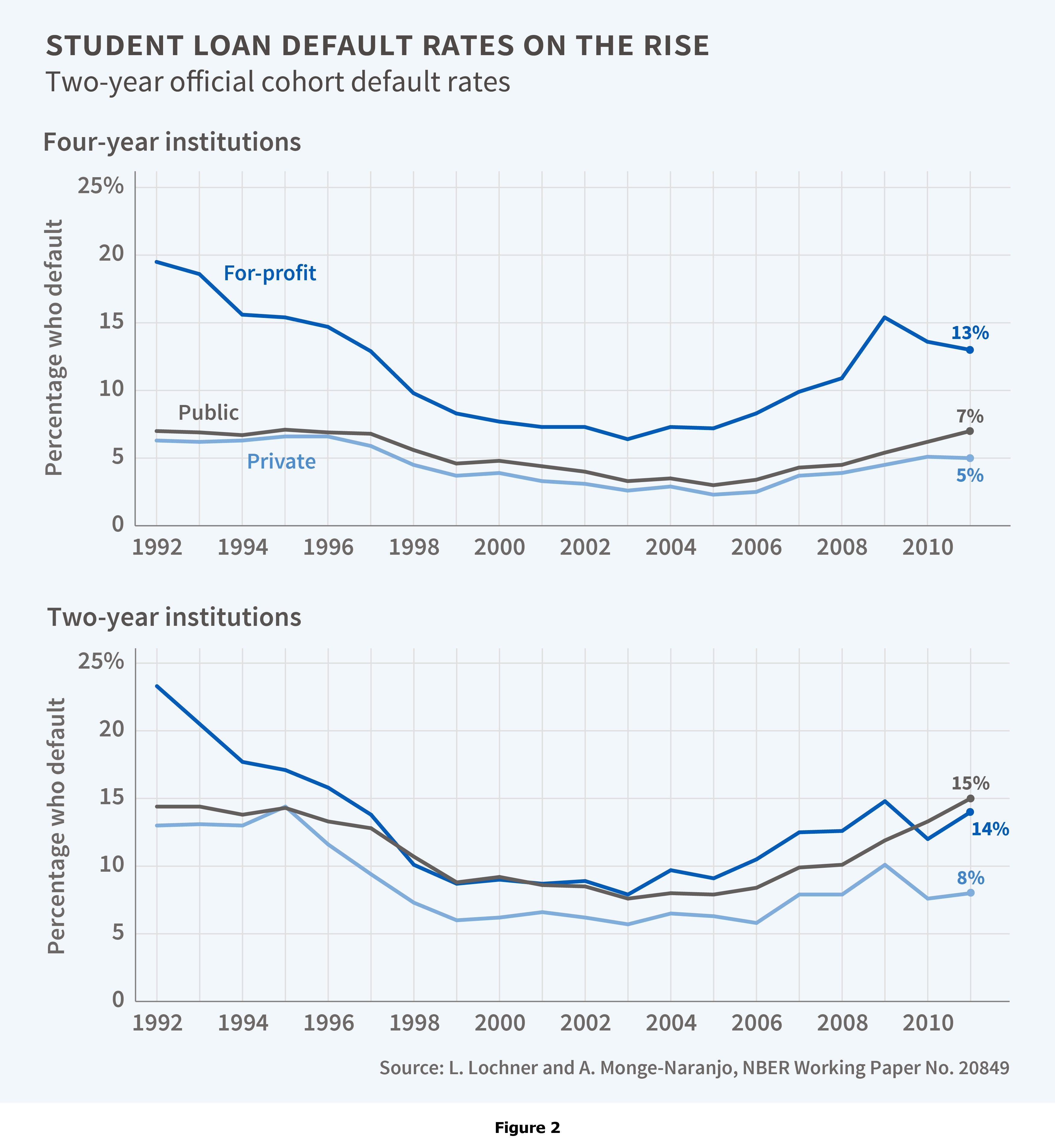

At the same time, there are concerns that many recent students are taking on too much debt. Growing levels of debt, coupled with rising labor market uncertainty and the last recession have led to a sharp increase in student loan default rates after more than a decade of decline. Borrowers who are 270 days or more (180 days or more prior to 1998) late on their Stafford student loan payments are considered to be in default. Figure 2 shows that two-year cohort default rates more than doubled between 2005 and 2011, with default rates increasing most at for-profit institutions and public two-year schools.

Altogether, these trends raise two seemingly contradictory concerns: Can today's college students borrow enough? Or, are they borrowing too much? Growing evidence suggests that both concerns are justified, with important implications for the design of student loan programs.

Can College Students Borrow Enough?

Monge-Naranjo and I document that the rising costs and returns of college, coupled with declining real government student loan limits, make it likely that credit constraints have become more salient in recent years.7 Indeed, one in three full-time/full-year undergraduates in 2003-04 exhausted their Stafford loan options.8 While many students have turned to private lenders for additional credit, the increased supply of private student credit was likely inadequate to satisfy the growing demands of many potential students. For example, private lenders typically require a co-signer for undergraduates, which leaves few alternatives for those whose parents have low income or a poor credit record.

Evidence on college-going further suggests an important increase in the extent to which credit constraints discouraged post-secondary schooling over the 1980s and 1990s. My research with Philippe Belley uses data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth to compare the relationship between family income and college attendance between cohorts completing high school in the early 1980s and the early 2000s.9 Consistent with previous studies,10 we estimate a weak relationship between family income and college-going for the earlier cohort. However, youth from high-income families in the later cohort are 16 percentage points more likely to attend college than their low-income counterparts, conditional on adolescent achievement and family background–roughly twice the gap observed for the earlier cohort. We further estimate that family income has become an important determinant of attendance at four-year (relative to two-year) colleges.

Uninsured labor market risk can discourage education in much the same way as credit constraints. Youth from low-income families may be unwilling to take on large debts to cover the costs of college when there is a possibility that they will not find good jobs after leaving school. By helping former students weather unexpected adverse labor market outcomes, explicit insurance mechanisms like unemployment insurance or student loan deferments and implicit insurance mechanisms such as the option to default on student loans can substantially affect the demand for credit and education.

Do Some Students Borrow Too Much?

An efficient student lending scheme should yield the same ex ante expected return from all borrowers even if ex post returns differ due to unpredictable labor market outcomes.11 While the focus of considerable attention, default during the first few years following school provides only a limited picture of lifetime payments and expected returns to lenders, since many students cycle through repayment and nonpayment states such as default and deferment during the first few years after school.

Using data from the 1993-2003 Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study (B&B), Monge-Naranjo and I analyze several different repayment and nonpayment measures to learn about the long-term expected returns/losses on student loans taken out by different types of college graduates.12 Our analysis simultaneously controls for individual and family background factors, college major, postsecondary institution characteristics, student debt levels, and post-school earnings.

Our results reveal considerable differences in ex ante expected losses across borrowers from different backgrounds and across those choosing different college majors. Most notably, race is correlated with student loan repayment and nonpayment. Ten years after graduation, black borrowers owe 22 percent more on their loans, are 9 percentage points more likely to be in nonpayment, and are in nonpayment on roughly 16 percent more of their undergraduate debt than white borrowers. These significant gaps cannot be explained by differences in choice of major, college type, or student debt levels.

While modest in comparison to differences between blacks and whites, there are also important differences in repayment or nonpayment across college majors. Students in engineering, health, and business programs perform well; humanities and social science majors perform relatively poorly. Differences in default by school type (public, private, for-profit) were insignificant for our sample of college graduates. Although student debt levels and post-school income are both important determinants of repayment problems–an additional $1,000 in debt can be roughly offset by an additional $10,000 in income–differences in these factors explain surprisingly little of the observed variation in repayment/nonpayment rates by race and college major.

While rarely acknowledged, personal savings and family assistance can serve as important sources of insurance for some student borrowers, influencing their post-school repayment behavior. Combining administrative data on student loan amounts and repayment with data from the Canada Student Loan Program's (CSLP) 2011–12 Client Satisfaction Surveys (CSS), Todd Stinebrickner, Utku Suleymanoglu, and I empirically examine the links between a broad array of available resources–income, savings, and family support–and student loan repayment in Canada.13

More than one-in-four CSLP borrowers in their first two years of repayment were experiencing some form of repayment problem at the time of the CSS. CSLP borrowers earning more than $40,000 per year had non-payment rates of only 2 to 3 percent, while borrowers with annual incomes of less than $20,000 were more than ten times as likely to experience a repayment problem. These sizeable gaps remain even after controlling for differences in demographic characteristics, educational attainment, views on the consequences of non-payment, and student debt.

Despite high nonpayment rates for borrowers with low post-school income, more than half of this group continued to make their standard student loan payments. Personal savings and family support are crucial to understanding this. Fewer than 5 percent of low-income borrowers with both savings and family support experienced a repayment problem, compared to 59 percent of low-income borrowers with negligible savings and little or no family help. Consistent with the hypothesis that savings and family transfers are important insurance mechanisms, we find that the likelihood of repayment problems is unrelated to post-college earnings for those with modest savings and access to family assistance. By contrast, among borrowers with negligible savings and little or no family assistance, the effects of income on repayment are extremely strong. This signals important gaps in the insurance provided by current student loan programs. Finally, we demonstrate that measures of parental income when students first borrow are a poor proxy for these other forms of self- and family-insurance, suggesting that efforts to measure savings and potential family transfers accurately offer tangible benefits.

Designing Efficient Student Loan Programs

In our most recent work, Monge-Naranjo and I consider the efficient design of student lending programs in an environment with uncertainty and common market imperfections that limit the extent of credit and insurance that can be provided.14 Efficient student loan programs must perform a difficult balancing act. They must provide students with access to credit while in school and help insure them against adverse labor market outcomes after school; however, they must also provide incentives for students to report their income accurately, exert efficient levels of effort during and after school, and generally honor their debts. They must also ensure that creditors earn an acceptable rate of return on their loans.

Based on our analysis, we discuss important lessons for the design of government student loan programs. For example, efforts to better equate expected repayments across borrowers by linking borrowing limits to observable characteristics and educational choices can improve the efficiency of lending programs and reduce default levels. Integrating the monitoring and collection efforts with other government collections (e.g. Social Security or income taxes) can yield similar benefits by reducing income verification and repayment enforcement costs.

We underscore the importance of recognizing the response of private lenders to changes in public higher education policies. Increased public investments in higher education may be met with additional private student lending if those investments improve post-college labor market opportunities.15 More importantly, government loan programs that offer similar terms to borrowers of different ex ante risk levels may be undercut by private creditors, leaving government programs with only the riskier borrowers.16

Endnotes

L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "The Nature of Credit Constraints and Human Capital," NBER Working Paper 13912, April 2008, and American Economic Review, 101(6), 2011, pp. 2487–529; L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo "Credit Constraints in Education," NBER Working Paper 17435, September 2011, and Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 4, 2012, pp. 225–56; and L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "Student Loans and Repayment: Theory, Evidence and Policy," NBER Working Paper 0849, January 2015.

Z. Bleemer, M. Brown, D. Lee, and W. van der Klaauw, "Debt, Jobs, or Housing: What's Keeping Millenials at Home?" Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 700, November 2014.

Students leaving school with lesser (or no) degrees acquire much less debt as shown by P. Steele and S. Baum, "How Much are College Students Borrowing?" New York, NY: College Board Publications, 2009.

L. Berkner, Trends in Undergraduate Borrowing: Federal Student Loans in 1989-90, 1992-93, and 1995-96. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, NCES 2000-151, 2000; C.C. Wei and L. Berkner, Trends in Undergraduate Borrowing II: Federal Student Loans in 1995-96, 1999-2000, and 2003-04, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2008.

L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "The Nature of Credit Constraints and Human Capital," NBER Working Paper 13912, April 2008, and American Economic Review, 101(6), 2011, pp. 2487-529; and L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "Credit Constraints in Education," NBER Working Paper 17435, September 2011, and Annual Review of Economics, 4(1), 2012, pp. 225-56.

L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "The Nature of Credit Constraints and Human Capital," NBER Working Paper 13912, April 2008, and American Economic Review, 101(6), 2011, pp. 2487-529; and L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo "Credit Constraints in Education," NBER Working Paper 17435, September 2011, and Annual Review of Economics, 4(1), 2012, pp. 225-56.

L. Berkner, Trends in Undergraduate Borrowing: Federal Student Loans in 1989-90, 1992-93, and 1995-96, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, NCES 2000-151, 2000; C.C. Wei and L. Berkner, Trends in Undergraduate Borrowing II: Federal Student Loans in 1995–96, 1999–2000, and 2003–04, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2008.

P. Belley and L. Lochner, "The Changing Role of Family Income and Ability in Determining Educational Achievement," Journal of Human Capital, 1(1), 2007, pp. 37-89.

P. Carneiro and J. Heckman, "The Evidence on Credit Constraints in Postsecondary Schooling," Economic Journal, 112(482), 2002, pp. 705-34.

L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "Student Loans and Repayment: Theory, Evidence and Policy," NBER Working Paper 20849, January 2015.

L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "Default and Repayment among Baccalaureate Degree Earners," in B. Hershbein and K. Hollenbeck, eds., Student Loans and the Dynamics of Debt, Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2015, pp. 235-85.

L. Lochner, T. Stinebrickner, and U. Suleymanoglu, "The Importance of Financial Resources for Student Loan Repayment," NBER Working Paper 19716, December 2013.

L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "Student Loans and Repayment: Theory, Evidence and Policy," NBER Working Paper 20849, January 2015.

L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "The Nature of Credit Constraints and Human Capital," American Economic Review, 101(6), 2011, pp. 2487-529.

L. Lochner and A. Monge-Naranjo, "Student Loans and Repayment: Theory, Evidence and Policy," NBER Working Paper 20849, January 2015.