Upcoding: Evidence from Medicare on Risk Adjustment

As private insurance plans increased market penetration, risk scores for seniors increased for reasons not explained by declining health or regional differences.

In 2014, some 50 million Americans were covered by health insurance companies that received public subsidies for patients who were considered high health risks. The subsidies were introduced over the previous decade to dissuade insurance companies from cherry-picking the healthiest customers in order to minimize their claim exposure and maximize profits.

But in addressing one problem, did government agencies introduce the potential for a new one? Are insurance companies gaming the system by encouraging doctors to overstate their diagnoses in order to increase subsidies?

The evidence suggests that may be the case, according to Michael Geruso and Timothy Layton in Upcoding: Evidence from Medicare on Squishy Risk Adjustment (NBER Working Paper No. 21222).

The authors studied Medicare Advantage, the largest health insurance market in the United States in which the public subsidizes the premiums of customers likely to require costly medical care. Through the Advantage option, seniors enroll in a private insurance plan, such as a health maintenance organization or a preferred provider organization, instead of relying on the traditional fee-for-service system. The private plans generally offer lower out-of-pocket costs and additional benefits, such as vision and dental care. But with the savings comes a tradeoff: enrollees are limited to a designated list of health care providers.

Demand for Medicare Advantage plans increased sharply in the wake of the 2006 Medicare Modernization Act, which included a new prescription drug benefit. Geruso and Layton found that as private insurance plans increased their market penetration, the overall average risk scores for seniors increased for reasons that could not be explained by declining health or regional differences. Further, they concluded that the "coding inflation" correlated with how closely tied the doctors were to the insurance plan, with the risk scores for enrollees in physician-owned plans 16 percent higher than otherwise would be expected.

Risk scores are based on an aggregation of a patient's medical diagnoses from the previous year. As coding is not an exact science, the process can be affected in subtle ways, such as how doctors' staffs are trained to interpret medical notes. By providing electronic forms pre-populated with the prior year's diagnoses, insurers can influence doctors to retain them. Further, an insurer might directly or through the doctor arrange annual checkups for enrollees with high risk scores so as to keep their diagnoses on the books. Finally, an insurer may directly compensate a doctor for more intense coding by risk adjusting the doctor's capitation payment, effectively tying the doctor's payment to the patient's diagnoses.

The researchers acknowledge that the costs of upcoding may be offset by the benefits to the patients of more attentive care, including visits to the patients' homes. However, they note, "regulators have expressed serious concern that such visits primarily serve to inflate risk scores."

Concerns about what would come to be known as upcoding became so pronounced by 2010 that the government began applying a deflator to risk scores. Without adjustment, upcoding in 2014 could have cost Medicare $10.5 billion or $640 per Medical Advantage enrollee. But even with adjustment, the authors estimate that upcoding still cost the public $2 billion last year, an average of $120 per enrollee. Since the deflator was applied uniformly, aggressive upcoders retained a larger share of their subsidies.

The authors note that upcoding may be distorting consumer choices, particularly in highly competitive markets. In such cases, insurers pass along a larger share of their subsidies to enrollees in the form of lower out-of-pocket costs and greater benefits. As a result, even more consumers enroll in Medicare Advantage, but their savings come at the expense of taxpayers as a whole.

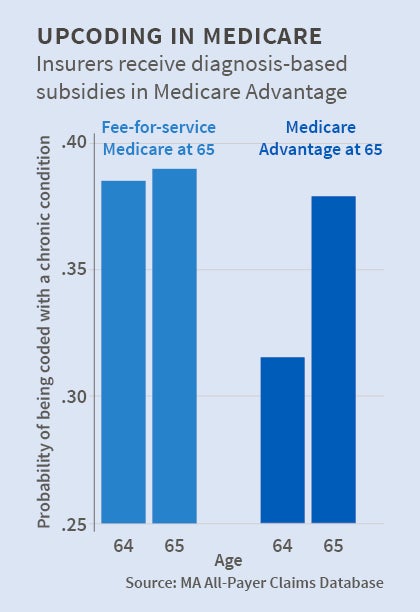

The authors based their findings primarily on national Medicare statistics broken down on a county level. As a supplement, they analyzed data in Massachusetts in 2011-12. They focused on people who switched from employer-paid health plans to Medicare upon turning 65. The reported health status of those who selected Medicare Advantage appeared to "immediately and dramatically worsen" relative to that of consumers who elected the fee-for-service system. By drilling down to examine coding for particular conditions, the researchers found that the greatest differences occurred on the extensive margin. For example, a Medicare Advantage patient showing borderline signs of diabetes was more likely to be diagnosed with the disease.

In their conclusion, the authors recommend that risk subsidies be linked to more broadly based data, such as a multi-year look at patient history. They also call for study of other risk-adjusted markets, noting the spread of risk adjustment to health insurance marketplaces under the Affordable Care Act.

—Steve Maas