Decentralization Helps Firms Cope with Downturns

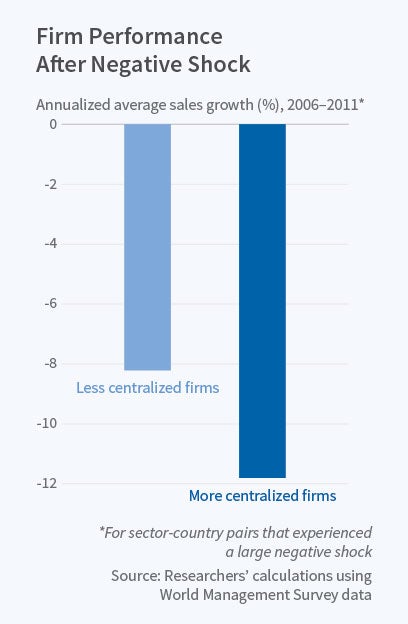

In sectors hit hard by the Great Recession, decentralized firms were more likely to survive. They experienced smaller declines in sales, productivity, and profits than their centralized counterparts.

The Great Recession sparked public debate about whether different approaches to organizing a firm affect its capacity to survive and recover from hard times. Are decisions about pricing, marketing, and hiring better made in corporate headquarters, by executives who can exploit a broad perspective, or by local plant managers, who have a more-intimate knowledge of conditions facing the product line but may lack a grander vision?

Philippe Aghion, Nicholas Bloom, Brian Lucking, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen find, in their study of Turbulence, Firm Decentralization, and Growth in Bad Times (NBER Working Paper 23354) that firms which delegated more decision-making responsibility to plant managers performed better in the years during and immediately after the global financial crisis. Recessions create large increases in uncertainty. When this happens, the researchers suggest, effective crisis management involves giving control to front-line managers who have a better sense of conditions on the ground than those at the center.

"[T]here is a trade-off between incentives and local information," they add. "Since there are agency problems between the CEO and plant manager, centralization may seem natural. But the plant manager is likely to have better local information than the CEO, which is a force for decentralization. When the environment becomes more turbulent, the CEO is even less well informed than in normal times. ... [L]ocal information becomes more important and decentralization becomes more valuable."

The researchers create two large micro datasets to study firm performance. One includes responses from 1,300 firms in 10 OECD countries to the World Management Survey; the other, constructed in cooperation with the Bureau of the Census from its Management and Organizational Practices Survey, covers 8,700 U.S. plants.

They find that in the years before the Great Recession, decentralized firms did not outperform centralized firms. During and after the downturn, however, decentralized firms in sectors hardest hit by the crisis did much better than their centralized counterparts. The researchers devise several measures of turbulence in an industry, such as "product churn," the ratio of the number of new products introduced and old products dropped to the number of products made. They find that the benefits of decentralization were greater in industries with greater product churn. Similarly, the benefits were larger in industries with greater increases in stock market volatility, another measure of market turbulence. Since turbulence rose most in sectors hit hardest by the crisis, this explains the outperformance of decentralized firms in crisis situations.

Decentralization can take many forms, and the form appears to matter for firm performance. Firms that delegate decisions about outputs, such as which products to produce and in what quantities, performed relatively better than firms that only delegated decisions about inputs, such as the amounts of labor and capital to employ.

Although organizational structure is slow to change and requires considerable investment, the researchers do observe a slow trend toward decentralization for the hardest hit firms. The greater the negative shock a centralized firm experienced, the more likely it was to decentralize after that shock.

The researchers conclude that the effects of decentralization are large enough to affect economic aggregates such as GDP. They find that greater decentralization in the United States could account for about 16 percent of the country's superior GDP growth following the Great Recession compared to other OECD countries in their sample.

— Deborah Kreuze