Evaluating Long-Horizon Macroeconomic Forecasts

Many public policy issues require judgement about long-run economic outcomes. The long-term feasibility of government spending programs and taxation depend on future prospects for variables such as growth, productivity, and interest rates on government debt.

In An Empirical Evaluation of Some Long-Horizon Macroeconomic Forecasts (NBER RDRC Working Paper NB21-18), researchers Kurt Lunsford and Kenneth West use data from 23 mostly developed countries to construct and evaluate forecasts for up to 50 years ahead for five variables — annual per capita GDP growth, CPI inflation, labor productivity growth, and long- and short-term interest rates.

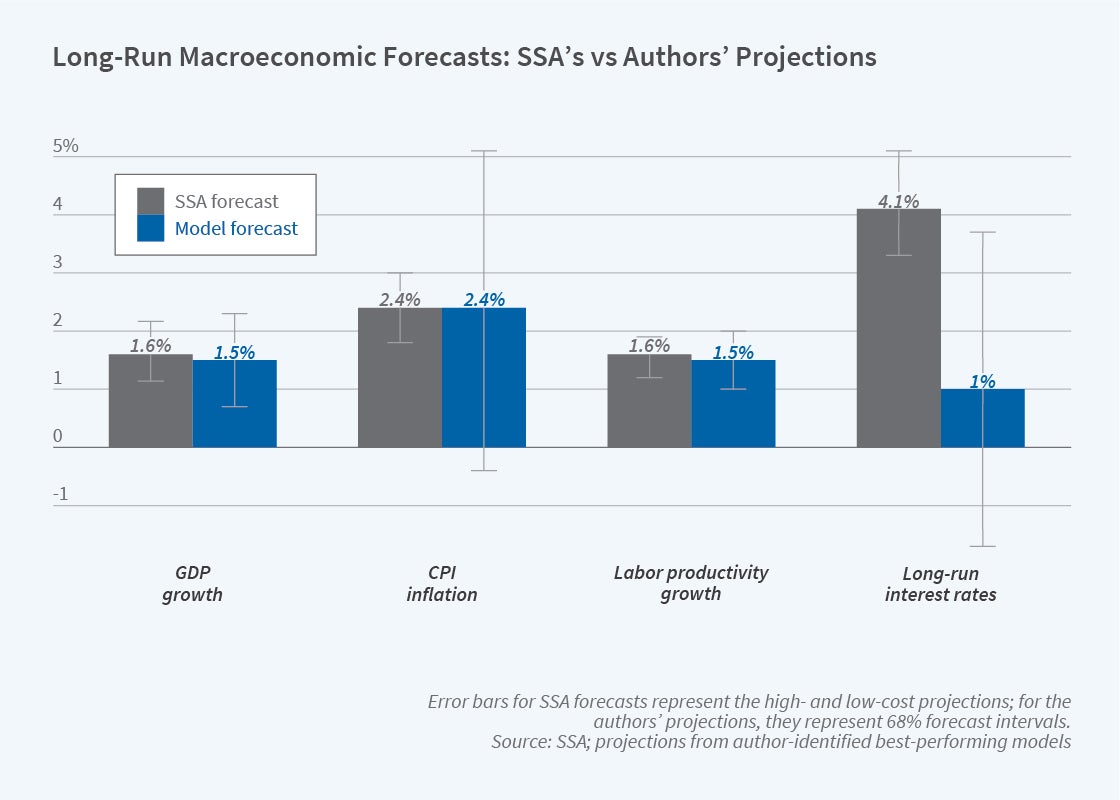

The authors compare their forecasts to the projections of the US Social Security Administration (SSA). The SSA makes projections for key economic variables up to 75 years ahead that, as the authors note, “are not the product of a formal economic model, and, for the most part, are not accompanied by formal measures of uncertainty such as confidence intervals around the projections.” The authors’ model-based approach complements the SSA’s approach.

The authors’ methods for forecasting each variable include simple time series models and frequency domain methods. In each case, they use 50 or more years of data to estimate the model, then construct a 68 percent forecast interval — that is, the interval in which average GDP growth (or another variable) would be expected to fall 68 percent of the time, based on model estimates — for a horizon of 10, 25, and 50 years in the future. Next, they compute the realized average growth rate over the 10, 25, and 50 years following the estimation period and note whether the realized value falls within the forecast interval. They evaluate their models based on whether “about 68 percent” of realized values fall within the forecast intervals and select their preferred models accordingly. The models work reasonably well for GDP growth, inflation and productivity growth, but less well for interest rates.

Turning to the comparison with SSA projections, the authors ask how the 68 percent forecast intervals produced by their models compare with the values used in SSA’s low- and high-cost scenarios. For GDP and productivity growth, SSA projections are basically in agreement with the authors’ models. For CPI inflation, the authors’ point estimate is slightly higher than the SSA projection and their 68 percent forecast interval is notably wider than the difference between the low- and high-cost projections. For long-term interest rates, the authors’ point estimate is distinctly below the SSA projection and the forecast interval is wider than the range implied by low- and high-cost projections.

The authors conclude, “taking our forecast and 68 percent forecast intervals at face value, this suggests that the US economy is likelier to breach the bounds of the low-cost and high-cost projections for CPI than for GDP or productivity growth, and still more likely to breach the bounds for interest rates.” They note that their study merely “lays the groundwork” for an alternative approach to long-horizon forecasts and that tasks for future research include consideration of a wider set of models for forecasting and for inference.

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the Federal Government, or NBER. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.