Is Medicare Advantage More Efficient than Traditional Medicare?

Medicare is the largest public insurance program in the U.S., with over 55 million elderly and disabled beneficiaries. Over time, this program has evolved to have a significant private component. The Medicare Advantage (MA) program offers beneficiaries the opportunity to enroll in a private health insurance plan (a HMO, PPO, or other coordinated plan) that is reimbursed by the federal government instead of traditional fee-for-service Medicare. In addition, beneficiaries who elect prescription drug coverage under Medicare Part D choose from a variety of private prescription drug insurance plans. More than 40 million Medicare beneficiaries have private insurance through MA or Part D plans.

An important motivation for the growing privatization of Medicare is the potential for private insurers to deliver health care services more efficiently than the government. Yet obtaining reliable evidence on this question is difficult. A key challenge is that individuals choose whether to enroll in MA or standard Medicare. Evidence suggests that MA beneficiaries are healthier than the Medicare population as a whole, so any differences in program expenditures may not necessarily reflect greater efficiency in the provision of care.

In their paper The Efficiency Consequences of Health Care Privatization: Evidence from Medicare Advantage Exits (NBER Working Paper No. 21650), researchers Mark Duggan, Jonathan Gruber, and Boris Vabson employ a novel strategy to explore this issue. The authors examine the change in health care utilization by MA beneficiaries after they switch to traditional Medicare because their private insurer has exited the market. By focusing on cases where there are no other MA providers in the county, the authors ensure that the change in MA status is unrelated to the individual's health or other characteristics.

The authors use hospital discharge data from New York State linked to data on Medicare enrollment. This gives them the unique opportunity to track individual-level hospital utilization for those in MA and those switching between MA and traditional Medicare. During their sample period, 8 counties experience the exit of all MA insurers, affecting 3 percent of MA enrollees. The authors' empirical approach isolates the effect of MA exit, allowing for trends over time and differences across counties in hospital utilization.

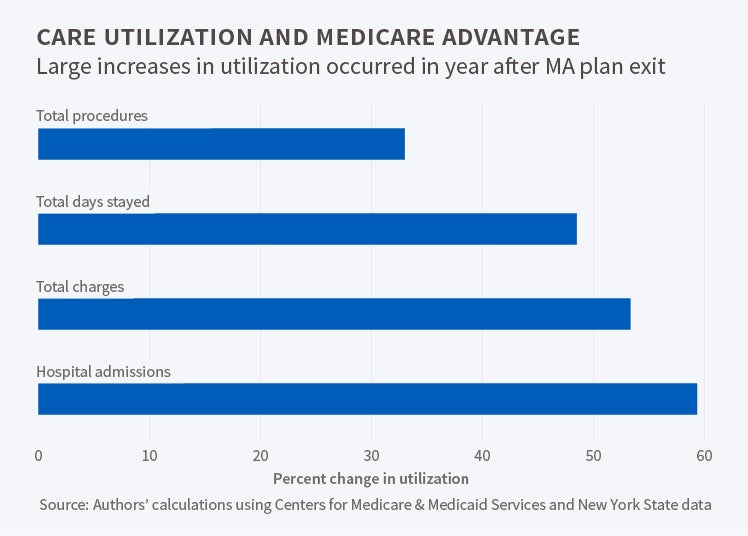

The central finding is that MA enrollees who are forced to switch to traditional Medicare due to MA exit experience an increase of 0.11 hospital admissions per capita, which represents a 60 percent increase relative to the mean of 0.18 admissions. This increase in hospitalizations is accompanied by a 48 percent increase in total days spent in the hospital, a 33 percent increase in the number of procedures, and a 53 percent increase in hospital charges.

If this increase represents "pent-up demand" by MA enrollees who were being treated less intensively, the increase in utilization should be temporary and fade over time. However, the findings do not support this hypothesis. The analysis also suggests that the effects of MA exit on utilization cannot be explained by other health care trends in the counties that experienced MA exit.

What might explain the lower hospital utilization of MA enrollees? The study's findings suggest two key mechanisms. The first is that MA plans restrict patients to hospitals that involve considerably longer travel. The second is that MA plans more tightly restrict elective and non-urgent hospitalizations. By contrast, the authors fail to find support for the theory that MA enrollees face higher cost-sharing than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.

Do MA enrollees who switch to traditional Medicare experience an increase in the quality of care? The authors find that traditional beneficiaries do not use higher quality hospitals. They also find that the odds of readmission and of having a preventable hospitalization rise after MA exit. "By these measures, therefore, quality is falling for those initially enrolled in MA following the exit of MA plans." Evidence on mortality is less conclusive, but if anything, mortality rises following MA exit.

In concluding, the authors note that the role of private players in public insurance has been a subject of debate, with advocates claiming that private insurers provide services more efficiently and detractors suggesting that private insurers enroll a healthier population and receive overly-generous reimbursements from the government. The authors contribute to this debate by documenting sizeable increases in hospital utilization among many dimensions when MA plans exit a county. They note several limitations of their work, including their inability to track inpatient care and to look at outcome measures beyond mortality. Nonetheless, they conclude, "our results suggest that there are large efficiencies from ensuring that at least some managed care option is available to enrollees." Future work could help to identify the tradeoffs of various alternatives to promote MA plan availability.

At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w21650.ack.