Exploring the Rise in Corporate Cash Holdings

Modest corporate investment relative to profitability and tax rules that discourage repatriation of foreign cash are key drivers of the recent increase in aggregate corporate cash.

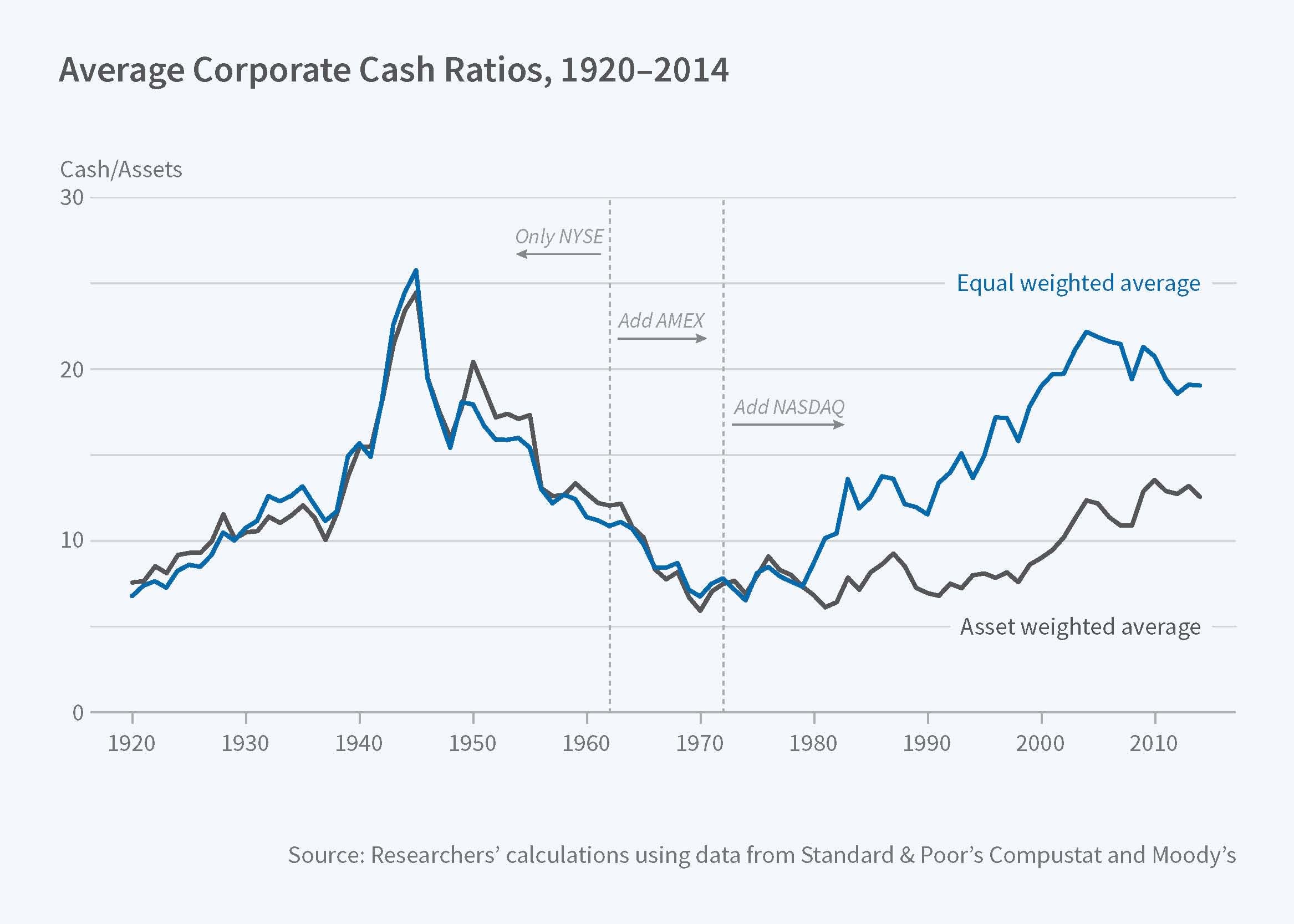

The total amount of cash held by corporations has increased since 2000, and some prominent firms have amassed very large cash holdings, raising questions about why this cash is not being invested or distributed to shareholders. To put these trends in context, and to understand recent developments in corporate cash management policy, John R. Graham and Mark T. Leary analyze almost a century of firm-level data. They find that, viewed in historical perspective, corporate cash holdings today are not unusual.

In The Evolution of Corporate Cash (NBER Working Paper No. 23767), the researchers analyze the relationship between firm characteristics and cash management policies, as well as how aggregate corporate cash holdings have evolved over time. They use data drawn from the monthly stock files of the Center for Research in Security Prices, Standard & Poor's Compustat, Moody's Industrial Manuals, and Internal Revenue Service Statistics of Income data. Despite dramatic shifts in transaction costs and informational frictions over the past century, they conclude that basic cash management practices have remained relatively stable: for the most part, firms of similar type have managed their cash holdings in similar ways throughout the past century. They do discover a new pattern for some firms in the period after 1980.

What has changed since 1980, the researchers say, is that newly public small firms in the health care and technology sectors report substantial cash holdings. The cash-to-assets ratios at these firms are often higher than those at much larger firms, a break from the historical pattern of similar cash holdings for small and large firms. These young firms draw down their cash in their first few years of operation, yet maintain relatively high cash ratios. While the emergence of these young, high-cash firms has affected the equal-weighted cross-firm average ratio of cash to assets, it has not been a key factor in the recent rise in aggregate cash holdings. The latter is much more dependent on the cash management practices of large firms.

The researchers explore the possibility that the cash management practices of firms of different sizes or in different industries have remained stable over time, but the relative importance of firms of different types has shifted. Such compositional changes might explain changes in aggregate cash holdings without changes in the behavior of a given type of firm. They do not find any compositional changes that explain the post-2000 rise in cash holdings, and conclude that macroeconomic factors, rather than changes in firm attributes, are likely to explain recent developments. High corporate profits, modest investment spending, and, especially since 2000, tax incentives that discourage repatriation of earnings by large multinational firms appear to have contributed to increasing aggregate cash.

One lesson of the historical analysis is that aggregate corporate cash holdings, relative to corporate assets or other measures of the size of the corporate sector, were substantially higher during the 1940s and 1950s than they are today. The reason for the run-up at that time, however, was different from the explanation of the recent rising trend. In the two decades following the Great Depression, precautionary savings appear to have been an important driver of increased cash holdings.

— Deborah Kreuze