The Impacts of Disability Benefits on Employment and Crime

A federal welfare reform that took effect August 22, 1996, required that low-income children with disabilities be medically evaluated as part of the Social Security Administration’s process for determining whether they would continue receiving cash assistance as adults in the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program.

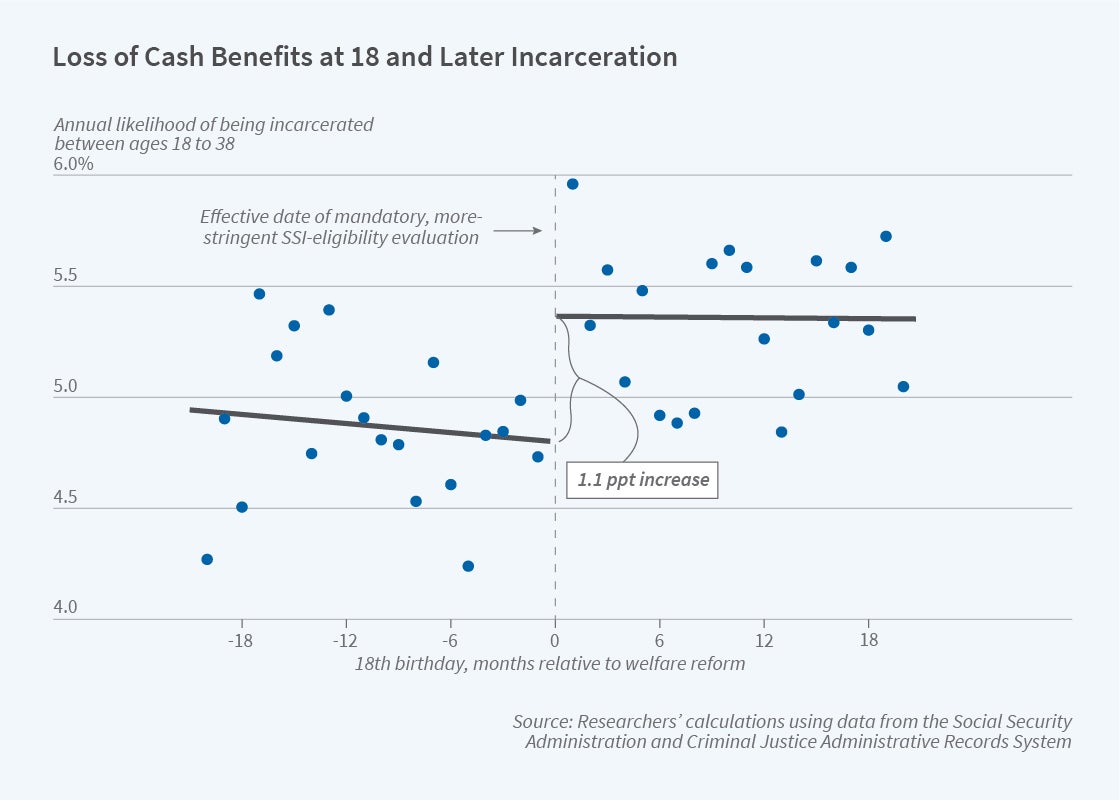

Nearly all children on SSI who turned 18 after the reform were evaluated to determine whether their disability impeded their ability to work enough to qualify them for cash benefits in adulthood. Most children with 18th birthdays before this date transitioned onto adult SSI without an eligibility review. After the reform, about 36 percent of those who were medically reviewed were removed from SSI, losing annual benefits of nearly $10,000 relative to those who remained in the program.

Removing low-income youth with disabilities from Supplemental Security Income at age 18 increased criminal charges associated with income generation as well as incarceration rates.

In Does Welfare Prevent Crime? The Criminal Justice Outcomes of Youth Removed from SSI (NBER Working Paper 29800), Manasi Deshpande and Michael G. Mueller-Smith utilize SSI records, earnings records, criminal court charges, and correctional data between 1997 and 2017 to examine how the loss of cash benefits affected the employment and criminal justice outcomes of 18-year-olds over the following two decades.

The researchers find that removing youth from SSI increased criminal charges substantially, with a 60 percent increase (from 0.63 to 1.0) in charges associated with income generation, such as theft and burglary. There was also a 60 percent increase — from 4.7 to 7.6 percentage points — in the annual likelihood of being incarcerated. Although SSI removal also increased the likelihood of youth working in formal employment — the fraction of youth earning at least $15,000 annually increased from 11 to 16 percent — the increase in criminal justice involvement was even larger. The share of those turning 18 who were subsequently charged with an income-generating crime rose from 24 to 33 percent following SSI removal. The researchers find that youth respond either by working more in the formal sector or by engaging more in criminal activity; very few respond on both margins.

The effects of SSI removal varied by subgroup. For men, the increase in criminal charges was concentrated in theft and burglary, and the annual likelihood of being incarcerated increased by 50 percent, from 7.2 to 10.8 percentage points. For women, the largest increases in criminal charges were for theft, prostitution, and forgery/fraud (e.g., identity theft), with a subsequent 230 percent increase in the annual incarceration rate, from 0.7 to 2.3 percentage points. The impact of SSI removal on incarceration was disproportionately high for youth with low-earning parents and Black young adults, two groups with high baseline incarceration rates.

The researchers assess the impact of SSI review on various government expenditures and find that the increased cost of enforcement and incarceration nearly eliminate the SSI savings. They estimate that removing a youth from the SSI program saved taxpayers an average of $49,000 through lower SSI and Medicaid spending and higher tax revenue due to increased adult earnings. However, they also find that the average increase in police, court, and incarceration costs associated with each SSI removal was $41,000. They estimate victim costs, using conservative assumptions, of $87,000 per removal.

— Aaron Metheny