The Role of Occupational Demands and Health in SSDI Application and Awards

The relationships between Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) determination, health, and occupation are complex. There are well-documented differences in health by occupation, which may reflect differences in job demands, social class, or selection into certain occupations based on underlying health conditions. In addition, evaluations of SSDI applications are based not only on health, but in many cases also consider age, education, and work experience though the use of the “medical-vocational grid” in the disability determination process.

In The Interaction of Health, Genetics, and Occupational Demands in SSDI Determinations (RDRC Working Paper NB20-11), researchers Amal Harrati and Lauren Schmitz examine these relationships in greater detail by disentangling their interacting and overlapping influence.

The analysis uses data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative dataset on Americans over age 50, linked to several specialized datasets. The first is Social Security data on SSDI applications and awards. The second is a registry of job demands, taken from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) database, which are matched to respondents’ longest-held job. The third is polygenic scores (PGSs), measures of genetic risk for conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and depression, which are constructed using individuals’ genotype data and findings from recent genome-wide association studies. Finally, data on childhood health and socioeconomic status are used to measure early-life factors that may jointly influence later-life health and selection into occupation.

The authors estimate stepwise models that examine the probability of SSDI outcomes as a function of occupation and, sequentially, job demands, education, childhood SES, and childhood health or genetic risk. The outcomes of interest are SSDI application, approval/denial (conditional on SSDI application), and whether approval was based on medical or work capacity reasons.

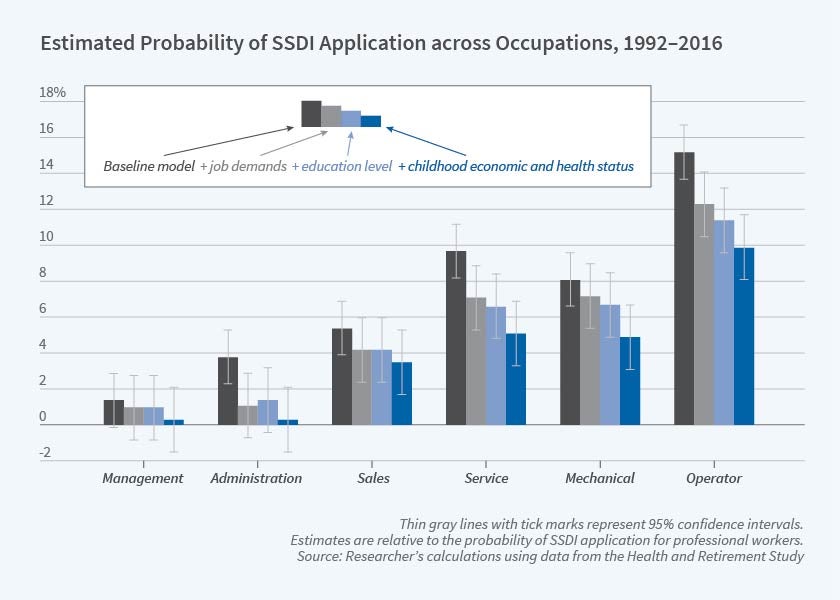

In the baseline model, there is a strong occupational gradient in SSDI application, with white collar workers being much less likely to apply for SSDI relative to their counterparts in blue collar and service occupations. There are similarly large differences across occupations in the probability of SSDI award.

Including job demands does little to change the relationship between occupation and SSDI application or award, with several key exceptions. The degree of control and influence a worker has over their day-to-day workload has a significant (negative) association with SSDI application, and occupational differences in SSDI application are smaller once this factor is taken into account. Among SSDI applicants, the probability of award is related to physical, mental, and sensory job demands, but not to psychosocial demands (such as whether the job gives workers a sense of achievement and independence), which may reflect the fact that the latter is not included in the medical-vocational grid.

Next, the authors examine the role of life course factors that may influence occupational choice, including education, childhood health, and childhood socioeconomic status. These factors are strongly associated with the probability of SSDI application, but do not have a strong association with the probability of an award among those who apply. Strong relationships between occupation and SSDI application remain even after including these life course factors. The authors note, “we interpret these findings to reflect the idea that structural and social inequities that influence access to opportunity and educational attainment (including race, childhood SES, and education) are important mechanisms in getting an individual 'to the door' of the SSDI system; however, conditional on SSDI application, approvals and denials appear to be a function of the determination process itself and not of larger, life course selection mechanisms.”

Finally, in additional analyses, the authors consider the role that health may play in SSDI application and receipt by using PGSs, which they conceptualize as a measure of unobserved health. Conditional on parental genetics, genetic markers are randomly assigned at birth, remain fixed across the life course, and confer (but do not necessarily determine) vulnerability towards specific health conditions. SSDI applicants have higher genetic risk for depression, BMI, myocardial infarction (MI), rheumatoid arthritis, and lower middle-age fluid cognitive function (which is associated with later dementia risk). These risks correlate with the health conditions cited in SSDI applications. However, genetic risk does not appear to be related to the probability of SSDI award among applicants or the reason for approval or denial.

The study’s findings have a number of potential implications for policy. First, non-SSDI policies that mitigate social and economic inequalities may affect SSDI caseload by influencing an individual’s future probability of applying to SSDI. The findings also corroborate the match between the medical-vocational grid used in disability determinations and the realized occupational experience of applicants. As a result, insofar as “the requirements of physical, mental, and sensory capacities in an applicant’s employment history are all important determinants in whether an individual’s application is approved, policies targeted at improving workplace conditions — including allowing workers in declining health additional accommodations or transfers to other positions — could help mitigate SSDI caseload.”

Finally, given associations between poorer childhood health, genetic vulnerabilities, and SSDI application, earlier health interventions, both at the workplace and in other settings, may help individuals with propensities towards poor health stay employed longer. The study’s findings “underscore the importance of early interventions in SSDI policy… These interventions have greater potential to improve the employment and well-being of adults with disabilities and to reduce reliance on SSDI benefits.”

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant #RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of NBER, SSA or any agency of the Federal Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.