Prescription Opioid Use After Injury and SSDI Enrollment

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) beneficiaries use prescription opioids at a higher rate than the general population. This may reflect the high prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and pain in the beneficiary population, but it also raises questions about whether opioid use affects entry into the SSDI program. Identifying the causal effect of opioid prescribing on SSDI participation is challenging due to the complex relationships between prescribing, local labor market conditions, health, and SSDI participation.

In Do Prescription Opioids After Traumatic Injury Increase the Risk of SSDI Entry? Instrumental Variables Estimates from the Colorado All-Payer Claims Database (NBER RDRC Working Paper NB20-02), researcher Michael Dworsky aims to shed light on this question. Traumatic injuries represent a change in health status that may trigger prescription opioid use. The author examines whether prescription opioid use after an injury-related visit to an emergency department (ED) is associated with SSDI entry and whether this differs for “opioid-naïve” patients vs. for patients with a history of prescription opioid use at the time of injury.

The data for the analysis come from the Colorado All-Payer Claims Database (APCD). The sample includes individuals ages 22 to 58 with employer-sponsored health insurance in their own names (and who thus are likely to be working) who visit an ED due to a traumatic injury (after a period of at least 12 months without an ED visit). While the database does not include data on SSDI awards, the author proxies for SSDI receipt using entry into the Medicare program before age 65, as SSDI beneficiaries become eligible for Medicare two years after disability onset.

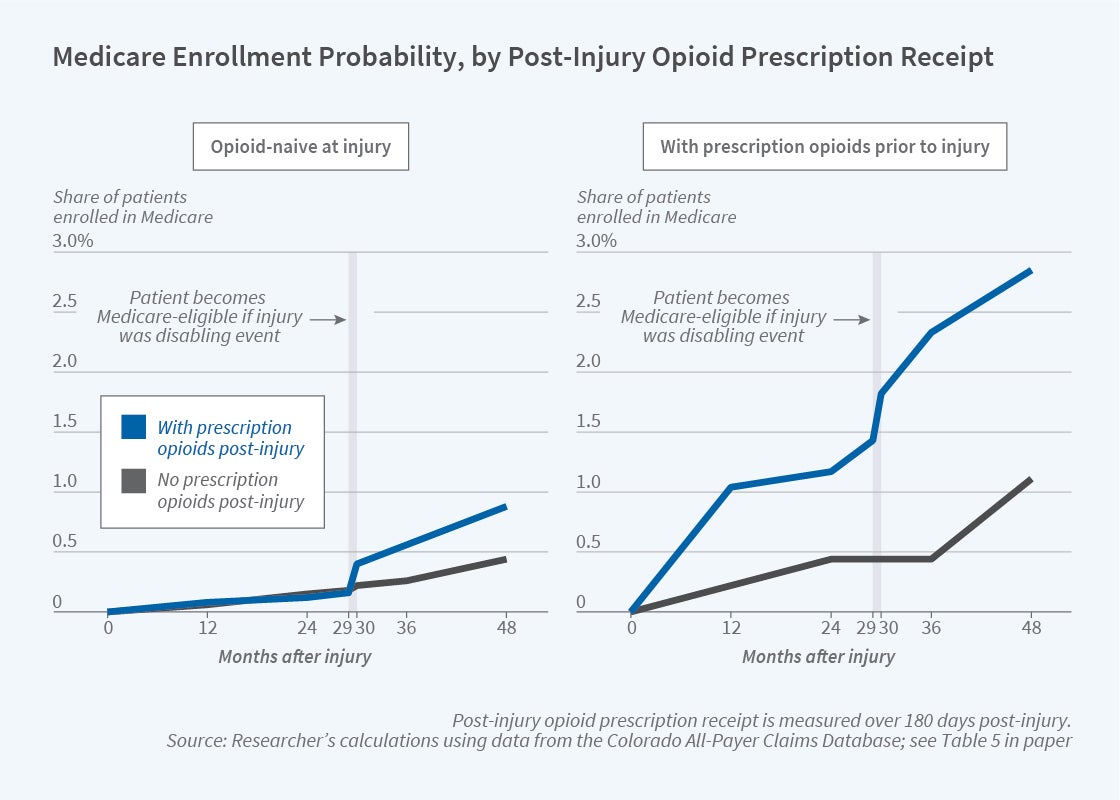

Opioid prescriptions in the months following an injury-related ED visit are common, with prescription opioid use rising by 25 percentage points after the visit. Turning to the relationship with SSDI, patients who are opioid-naïve are much less likely to enter Medicare within four years of injury than patients with a history of prescription opioid receipt. Interestingly, among the opioid-naive, those who receive a prescription for opioids after their injury are twice as likely to enter Medicare as those who do not receive such a prescription. Similarly, among those with a history of prescription opioid use, those who receive prescription opioids post-injury are 2.5 times as likely to enter Medicare. These differences largely persist after controlling for differences in injury type, demographics, and pre-injury comorbidities.

As the author notes, these estimates cannot be interpreted causally because opioid prescribing is likely to reflect unobserved differences in health status and disability risk. To surmount this, the author focuses on differences in the probability of opioid prescription after injury that arise because of differential prescribing patterns across health insurers. While there is no association between post-injury prescription opioid use (as predicted by insurer prescribing behavior) and entry into Medicare for the sample as a whole, opioid use is associated with entry into Medicare for the sub-sample of adults ages 50 to 58 at the time of injury. These results are only marginally statistically significant, however, and should be viewed only as suggestive evidence that post-injury prescription opioid receipt increases the risk of transitioning from employment to SSDI.

The author concludes that “the descriptive findings presented here on associations between pre- and post-injury opioid receipt and Medicare enrollment may be of interest to policymakers and clinicians for purposes of targeting interventions to help individuals remain employed or in the labor force after traumatic injuries.”

The research reported herein was derived in whole or in part from research activities performed pursuant to grant RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the Federal Government, or NBER. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.